“We are holding our own.”

Honoring the SS Edmond Fitzgerald

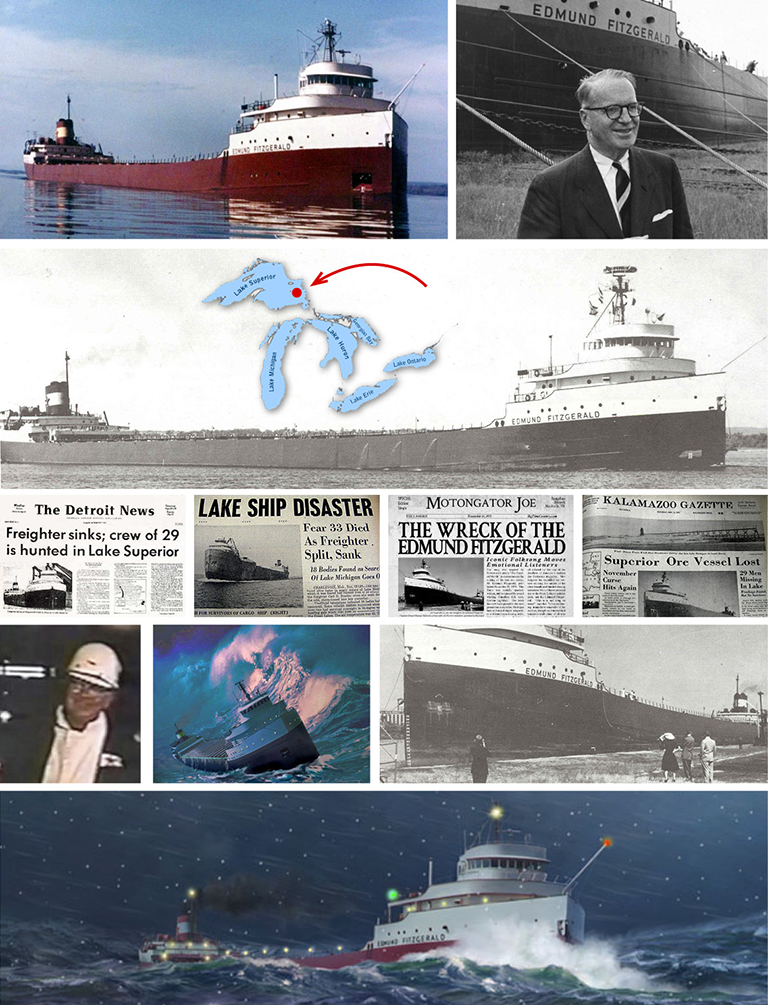

Various paintings, newspaper headlines and news photos.

Upper right: Namesake, Edmund Fitzgerald, president of Northwestern Mutual, stands in front of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald in July 1959. (Image credit: Wisconsin Marine Historical Society)

Second row from bottom, far left: Bay Village resident, John H. McCarthy, First Mate.

As I sit in my office on Detroit Avenue, I have the luxury of overlooking a magnificent view of beautiful Lake Erie, watching freighters come and go in our busy docks. This week is a special week, as it marks 40 years since the loss of the Edmond Fitzgerald, a tragedy made famous by singer/songwriter Gordon Lightfoot. For our history and boating buffs out there, I thought I’d research a bit more about this mighty freighter and share with our group some known and unknown facts.

- SS Edmund Fitzgerald, the largest freighter of her time when launched, sank in a Lake Superior storm with the loss of the entire crew of 29.

- For seventeen years, and recording over 1M nautical miles, Fitzgerald carried taconite iron ore from mines near Duluth, MN to iron works in Detroit, Toledo, and other Great Lakes ports. A “workhorse,” she set seasonal haul records six times, with a deadweight capacity of over 26,000 tons.

- “DJ” Captain Peter Pulcer was known for piping music day or night over the ship’s intercom while passing through the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers and entertaining spectators near the locks with a running commentary about the ship.

- Financed by the Northwestern Mutual Insurance Company of Milwaukee, and named after its Chairman of the Board, (who’s grandfather had also been a sea captain) she was the longest freighter built – “within a foot of the maximum length allowed for passage through the soon-to-be-completed Saint Lawrence Seaway” – 730 feet long and 75 feet wide, earning her the title “Queen of the Great Lakes”

- Up until a few weeks before her loss, passengers had traveled on board as company guests and were provided VIP treatment with excellent snacks and a well-stocked kitchenette for drinks. Once each trip, the captain held a candlelight dinner for the guests, complete with mess-jacketed stewards and special “clamdigger” punch.

- Carrying a full cargo of ore pellets with Captain Ernest M. McSorley in command, she embarked on her ill-fated voyage from Superior, Wisconsin, near Duluth, on the afternoon of November 9, 1975.

- At 2:00 a.m. on November 10, the NWS upgraded its warnings from gale to storm, forecasting winds of 35–50 knots (40–58 mph). Until then, Fitzgerald had followed a sister ship the SS. Anderson, but pulled ahead about 3:00 a.m. As the storm center passed over the ships, they both experienced shifting winds, as wind direction changed from northeast to south and then northwest.

- Shortly after 3:30 p.m., Captain McSorley radioed the Anderson to report that Fitzgerald was taking on water and had lost two vent covers, a fence railing and had also developed a list. Two of Fitzgerald’s six bilge pumps ran continuously to discharge shipped water.

- For a time, Anderson directed Fitzgerald toward the relative safety of Whitefish Bay. Some time later, McSorley told Anderson, “I have a ‘bad list,’ I have lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck in one of the worst seas I have ever been in.” With sustained winds of 58 mph, gusts up to 78 mph, and waves between 25-35 feet, the last communication from the ship came at approximately 7:10 p.m., when Anderson notified Fitzgerald of an upbound ship and asked how she was doing. McSorley reported, “We are holding our own.” She sank minutes later.

- The wreck was discovered weeks later, finding the Fitzgerald lying in two large pieces on the lake floor. In 1980, a research dive expedition was led by Jean-Michael Cousteau (son of Jacques Cousteau) and concluded the vessel most likely broke on the surface.

- Over the years, hundreds of thousands of dollars have been spent on dozens of dives to determine the cause, look for crew and also retrieve artifacts. Theories include rogue wave impact, cargo hold flooding, shoaling (grounding), structural failure, and topside damage/flooding. No conclusive evidence exists to date.

- The sinking led to changes in Great Lakes shipping regulations and practices that included mandatory survival suits, depth finders, positioning systems, increased freeboard, and more frequent inspection of vessels.

On November 10:

Twenty-nine bells for the twenty-nine lives lost on the Edmond Fitzgerald.