Drifting Away

Growing up and living most of my life in Northeast Ohio gives me a somewhat unique perspective on snow, snowstorms, and snow drifts. I can’t count how many times I’ve ventured down the driveway to shovel, only to find a big drift wrapping around the car or garage. Part PIA (pain in the @%$) and part beauty, I find myself slice carving sections out with my shovel to then throw the snow onto the lawn, clearing the driveway (for a little while). I can remember, as a kid back in 1978, before I-480 was opened, we were driving down Brookpark Road by the Cleveland Hopkins Airport – the snow was so high that we could not see over the fences on either side of the road, just a long white tunnel! That year, we also had drifts of almost 40’! For those of you who live in the northeast, you’ve likely noticed how storms are less severe than years ago (“when I was a kid, we walked 8 miles to school, barefoot, against the wind both ways, without jackets…”). Even though I’m fascinated by the drifts, at times, I must admit, sometimes they are a “pain”. These days I have a very nice snowblower, which allows me to occasionally start at my driveway and proceed down to the corner of the street and come back!! Yup -a man with his toys! Here’s some cool science about snow and drifts I think you’ll find fascinating, along with a bit of big storms trivia. Stay warm and enjoy!

Nice winter song while you read

Snow drifts are fascinating natural formations created when wind transports loose snow, depositing it in mounds or ridges, especially near obstacles and open areas. The science behind snow drifts involves wind dynamics, snow crystal formation (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snowflake), and thermodynamics, all working together to shape these unique winter landscapes.

Wind is the driving force behind snow drift formation. Snow doesn’t drift by itself without wind. When the wind blows over snowy terrain, it picks up loose snow and carries it across the landscape. Where wind slows down, after encountering obstacles, or on leeward slopes, snow is deposited, building up drifts and unique shapes.

Snow drifts form because wind picks up loose, granular snow and moves it across open ground. This transport occurs in three main ways:

- Creep: At lower wind speeds, snow particles roll or slide along the ground.

- Saltation: As wind speed increases, particles are briefly lifted into the air and bounce along the surface.

- Suspension: At high wind speeds, snow particles are carried higher in the air, sometimes up to hundreds of feet, creating conditions like whiteouts during blizzards.

Obstacles such as fences, buildings, parked cars, or natural terrain slow the wind, causing snow to settle and accumulate in distinctive piles, called drifts. Eddies and turbulence behind these obstacles enhance snow deposition.

Snow drifts often resemble desert dunes and form via similar physics—both are shaped by wind transporting granular material. Under the right conditions, snow can even form arches or bridges across crevasses in cold regions. On open highways, snowplows create barriers along the roadside that entice snow to fall and drift.

Most drifts shimmer white and blue, but in rare cases, “watermelon snow” gets its pink tint from cold-loving algae. Sometimes, drifts get creative—forming natural snow “bridges” across crevasses in the mountains.

There are two types of snow fences – living and structural. A living snow fence is a group of trees or bushes planted strategically to catch drifting snow. The line of trees or shrubs prevents the snow from reaching sections of roads that tend to become blocked during or after storms, creating an effective barrier and increasing driver safety.

Engineers automatically design roads for drainage, but snow should receive the same attention, particularly in states that experience winter weather for half the year. As you navigate your way through winter driving conditions, take notice of what surrounds you. The line of trees or the ditch next to you may just be helping keep the roadway clear.

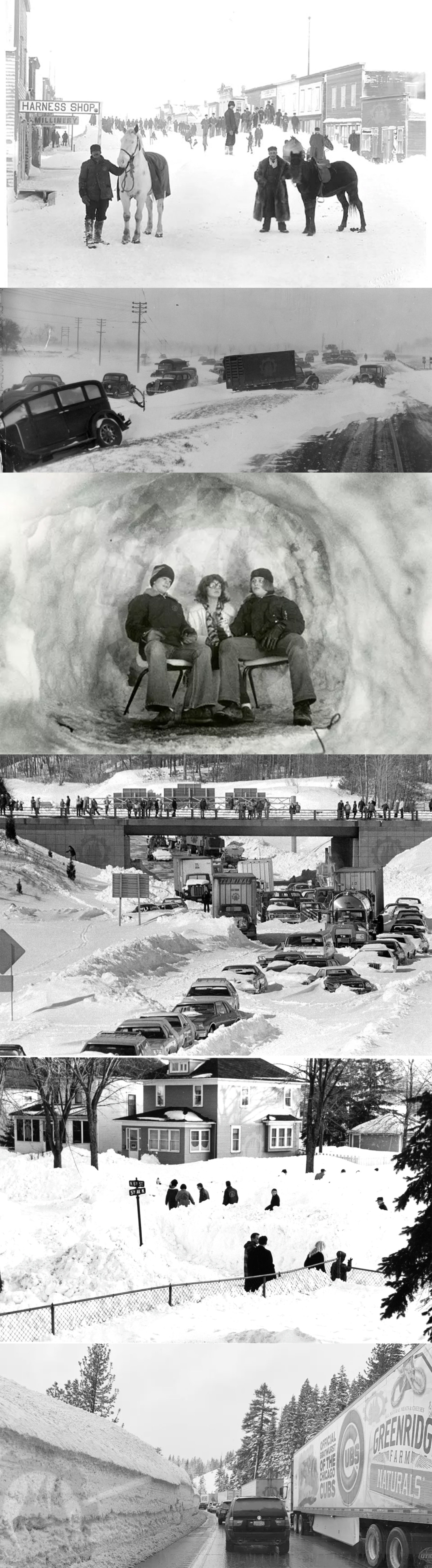

Some Storms of Note:

The Schoolhouse Blizzard (January 12, 1888) – Also known as the Children’s Blizzard, this devastating storm hit the Great Plains just months before the “Great White Hurricane.” Striking suddenly on a mild winter day, it caught thousands of settlers and schoolchildren by surprise across Nebraska, the Dakotas, Kansas, and Minnesota, with drifts up to 50 feet. High winds and a sharp temperature plunge led to over 230 deaths, many of them children trapped in rural schoolhouses or trying to walk home.

The Armistice Day Blizzard (November 11–12, 1940) – A violent Upper Midwest storm that arrived without warning, bringing 70-mph winds, lightning, sleet, and over two feet of snow across Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa. Temperatures plummeted 50 degrees in less than 24 hours. Many duck hunters were caught on lakes and rivers, leading to at least 150 fatalities.

The Blizzard of 1977 was a catastrophic storm that hit Western New York in late January 1977, causing widespread devastation with heavy snowfall, high winds, and extreme wind chills. The storm brought over eight feet of snow to some areas, with winds reaching 69 mph and creating snowdrifts up to 40 feet high, stranding thousands of people, closing roads, and leading to over 20 deaths. The blizzard’s extreme conditions, including a wind chill of -50∘F, made it one of the most destructive weather events in the region’s history.

The Great Blizzard of 1978 This is not the New England storm of February that same year — this one slammed the Ohio and Great Lakes region, with record low pressure rivaling hurricanes. Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan were buried under more than two feet of snow, with drifts as high as 20 feet and thousands stranded. It remains one of the Midwest’s worst weather events of the 20th century. Yup – this is the one I experienced growing up – Amazing!

Mountain West – Colorado Blizzard of 1913 Denver was buried under 45 inches of snow — its greatest total ever recorded — and mountain towns received up to 6 feet. Transportation ground to a halt, livestock losses were immense, and the storm effectively shut down much of Colorado for a week.

Northern Plains and Rockies – North Dakota Blizzard of 1966 A ferocious storm with wind gusts up to 70 mph produced drifts so high they covered houses and telephone poles. Rural residents were stranded for days, and dozens of lives were lost across the High Plains. Photos from that storm, showing entire trains buried, remain iconic in regional weather history.

Pacific Northwest and West Coast – The Seattle “Big Snow” Unusual cold followed by heavy snow buried the Seattle area under 21 inches, paralyzing a city unaccustomed to such conditions. Roofs collapsed, and fuel shortages added to the hardship, making this one of Washington state’s most memorable winter events.

Sierra Nevada Snowstorm of February 2019 Over a 10-day span, parts of the Sierra Nevada range received more than 25 feet of snow, closing mountain passes and cutting off resort towns. This modern storm was a reminder of California’s vulnerability to extreme winter weather even amid long-term warming trends.

The “worst” recorded snowstorm depends on the criteria, but the Mount Shasta storm of 1959 holds the record for the greatest single-storm snowfall in North America (189 inches in about a week). Other candidates for “worst” include the 1978 Great Blizzard for its impact on the Ohio Valley and the 1993 “Storm of the Century” for its widespread effects.

Ok, that’s enough – go make some hot chocolate and stay warm !! – Gas fireplace logs do wonders!

How did you do on last week’s logo contest?

Check out our logo guide for the “Body Beautiful” post here!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!