Pickle Day

One of the most fun, a bit quirky, but oh so good snacks out there are – pickles. Crispy, crunchy, tangy, salty, dilly, yummy, and sometimes sweet, whole, spears, or chips, pickles are one of those foods most of us love… (you either can’t get enough of them… or you politely slide them off your sandwich dish onto someone else’s plate). Now of course I have multiple “favorites” Bread and Butter Pickles – both regular and zesty which my grandson calls Grandpa’s SPICY pickles and those good old fashioned barrel pickles! But love them or not, pickles have been around for thousands of years, and today, November 14th, we can celebrate them in all their briny glory on National Pickle Day. Add a spear to a dog, and its heaven (plus tangy pickled relish). Small delights on a relish tray – I’m in. And getting one of those big guys out of a pickle barrel is wonderful. And how they get those pickles into a jar amazes me (talk about a PIA (pain in the @%$) Job!). To learn more about pickles, and NPDay I went “crunching” online to find some fun facts and trivia I think you’ll enjoy. And be sure, when you get home today, reach in the back of the fridge, open a jar of your favorites, and snack away. Enjoy!

A pickled cucumber – commonly known as a pickle in the US and Canada and a gherkin (/ˈɡɜːrkɪn/ GUR-kin) in Britain, Ireland, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand – is a usually small or miniature cucumber that has been pickled in a brine, vinegar, or other solution and left to ferment. The fermentation process is executed either by immersing the cucumbers in an acidic solution or through souring by lacto-fermentation. The word pickle comes from the Dutch word pekel, meaning “brine.”

The term traditionally used in British English to refer to a pickled cucumber, gherkin, is also of Dutch origin, derived from the word gurken or augurken, meaning cucumber

Preserving foods in vinegar, brine or a similar solution is one of the oldest methods of food preservation. Though the exact origins of the process are unknown, archaeologists believe ancient Mesopotamians pickled food as far back as 2400 B.C.,

Queen Cleopatra of Egypt credited the pickles in her diet with contributing to her health and legendary beauty. Meanwhile, Cleopatra’s lover Julius Caesar and other Roman emperors gave pickles to their troops to eat in the belief that they would make them strong.

During the Age of Exploration (~1492), many sailors on transoceanic voyages suffered from scurvy, a nasty but all-too-common disease caused by a deficiency of Vitamin C. On his storied expedition to the New World, Christopher Columbus reportedly rationed pickles to his sailors, even going so far as to grow cucumbers in Haiti to restock for the rest of the trip. And that’s not all: Before he was an explorer, Amerigo Vespucci worked as a ship’s chandler in Seville, Spain—meaning he supplied ships with goods like preserved meat and vegetables. Known as the “Pickle-Dealer,” Vespucci even helped stock Columbus’s ships on his later, less successful voyages across the Atlantic.

By 1659, Dutch farmers in New York had begun growing cucumbers in the area that is now Brooklyn. Dealers bought the cucumbers, pickled them and sold them out of barrels on the street, beginning what would become the world’s largest pickle industry. Later waves of immigration to New York in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including large numbers of Eastern European Jews, who introduced kosher dill pickles to America, would cement the city’s place at the center of the pickle world.

In 1809, Napoleon Bonaparte had offered to pay 12,000 francs (the equivalent of today’s $250,000) to the person who could come up with the best way to pickle and preserve food for his troops. French chef and confectioner Nicolas Appert, won the competition with a key insight: If he placed food in a bottle and removed all the air before sealing it, he could boil the bottle and preserve its contents. Using glass containers sealed with cork and wax, Appert was able to preserve not only vegetables and fruits, but also jellies, syrups, soups and dairy products.

Early in the 1850s, the Scottish chemist James Young patented paraffin wax, which created a better seal in jars used to preserve food. Then in 1858, John Mason of Philadelphia patented the first Mason jar, made from a heavyweight glass that could withstand high temperatures during the canning process. Mason’s patent expired in 1879, but manufacturers of similar jars continued to use the Mason name (now you know!!)

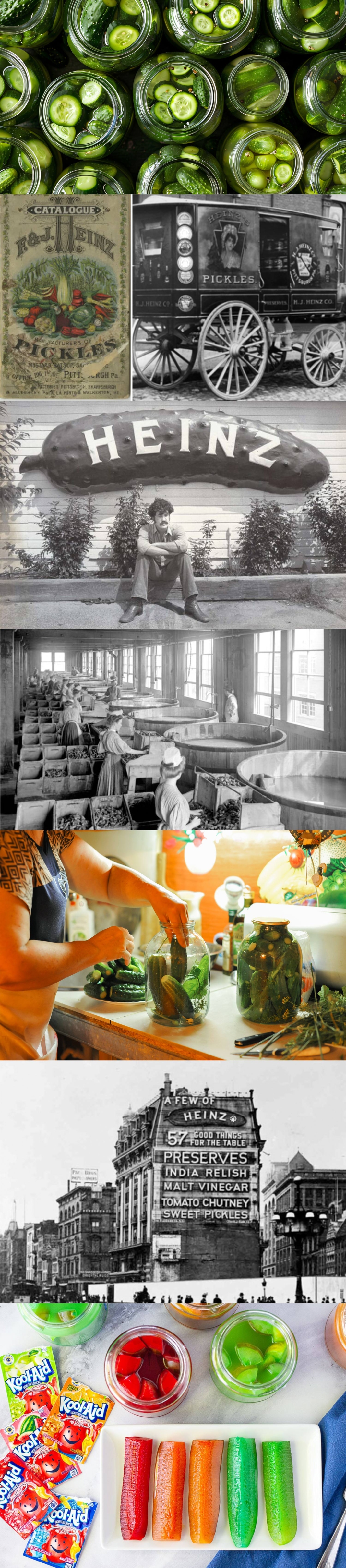

At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, “Pickle King” H.J. Heinz dispatched a few local boys to tempt fairgoers with a “free gift” if they visited Heinz’s out-of-the-way booth and tasted his wares. By the end of the fair, Heinz had given out some 1 million “pickle pins,” launching one of the most successful marketing gambits in U.S. history. H.J. Heinz Company, Inc. repeated the pickle pin promotion at the World’s Fairs of 1896, 1898 and 1939. Heinz’s dark-green pickle pins can still be bought today, joined by spin-offs like the ketchup pin and the golden pickle pin.

During World War II, the U.S. government rationed pickles, and 40 percent of the nation’s production of pickles went to the armed forces. In 1948, the trade organization Pickle Packers International, founded in 1893, launched International Pickle Week. Go ahead, say it…”Peter Piper Picked A Pack….”

After beating the Dallas Cowboys 41-14 on a day when temperatures reached 109˚ F, players from the Philadelphia Eagles football team famously credited their endurance to drinking pickle juice. A later study at Brigham Young University backed these claims with science, showing that knocking back pickle juice “relieved a cramp 45 percent faster” than drinking no fluids and about 37 percent faster than water.

America eats a lot of pickles—about 9 pounds per person per year. The biggest pickle festival is in Rosendale, New York, where pickle ice cream, pickle beer, and even pickle pizza are on the menu (our local restaurant sells this – yummy!!) There’s even a tradition in some homes of hiding a “Christmas Pickle” ornament on the tree—first child to find it gets an extra present!

Lime – Lime pickles are soaked in pickling lime (not to be confused with the citrus fruit) rather than in a salt brine. This is done more to enhance texture (by making them crisper) rather than as a preservative. The lime is then rinsed off the pickles. Vinegar and sugar are often added after the 24-hour soak in lime, along with pickling spices. The crisping effect of lime is caused by its calcium content.

Kool-Aid pickles – Kool-Aid pickles, or “koolickles”, enjoyed by children in parts of the Southern US, are created by soaking dill pickles in a mixture of powdered Kool-Aid and pickle brine. Southern Living reported that fruit punch and cherry Kool-Aid were the most popular flavors for pickling. The flesh of Kool-Aid pickles typically takes on a pink color.

Dill pickles can be fried, typically deep-fried with a breading or batter surrounding the spear or slice. This is a popular dish in the southern US and a rising trend elsewhere in the US. (I love them!)

In Russia and Ukraine , pickles are used in rassolnik: a traditional soup made from pickled cucumbers, pearl barley, pork or beef kidneys, and various herbs. The dish is known to have existed as far back as the 15th century when it was called kalya.

In southern England, large gherkins pickled in vinegar are served as an accompaniment to fish and chips and are sold from big jars on the counter at a fish and chip shop, along with pickled onions. In the Cockney dialect of London, this type of gherkin is called a “wally”.

In the US, we consume about 20 billion pickles each year. (that’s like 54 million a day!)

“In a pickle” – Ever find yourself in a tough spot? You’re “in a pickle.” This phrase dates back to the 1500s, and Shakespeare even used it in The Tempest. The idea: just like a cucumber soaking in brine, you’re stuck in an uncomfortable mess.

“A pickle” – Before it was food, “pickle” could mean a rascal or mischievous child. If someone in the 16th century called you “a pickle,” they probably meant you were a bit of a troublemaker!

“To get pickled” – No jars required. To “get pickled” is to get drunk — slang that started in the 1700s. People soak up alcohol like cucumbers soak up brine, and the nickname stuck.

“Pickled” (adjective) – Besides describing preserved veggies, “pickled” can also mean plastered. Sailors in the 19th century joked about being “pickled in rum.”

“In a pickle” (Baseball Edition) – In America’s pastime, a runner caught between two bases while fielders toss the ball back and forth is said to be “in a pickle.” Or “pickle in the middle”. Just like the phrase’s original meaning, it’s a tight and uncomfortable spot to be in.

“Cool as a cucumber” – Technically pre-pickle, but still part of the family! This 1700s phrase comes from the fact that cucumbers are cool inside even on a hot day. It means staying calm under pressure — no sweat.

“A dilly” or A dilly of a pickle” – Now this one’s extra tangy. A “dilly” can mean delightful or tricky, depending on who’s saying it. Put it together with pickle, and you’ve got a phrase for a problem that’s hard to solve… or something delightfully unique.

How did you do on last week’s logo contest?

Check out our logo guide for the “Salt and Peppah” post here!

Image sources:

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!