Sneak a Kiss

I just love the holidays and holiday traditions. For me, they never get tired – all the fun, music, nostalgia, and decorations just add to the holidays. So, after taking down the Halloween decorations and putting away the Thanksgiving decorations, it’s now time to be sure we decorate for Christmas in my house. Jackie does a wonderful job, mixing in things we’ve inherited from the family with things of our own, to one day pass along to the kids and grandkids. And one of my favorites is to hang some mistletoe in the doorway, with hopes of stealing a kiss here or there again and again from Jackie! I wanted to learn more about where mistletoe comes from, and the history behind it, and of course, I turned to the internet. I hope you enjoy the info and make mistletoe a tradition in your home, too. ENJOY!

Fun Music to listen to while you read!

Mistletoe isn’t just a cute excuse to steal a kiss under the doorway – it’s a real, living plant with a surprisingly wild lifestyle. Botanically speaking, mistletoe is a parasitic evergreen, which means it grows directly on the branches of other trees and shrubs, stealing water and nutrients from its host.

The plant’s name actually has a rather earthy origin. “Mistletoe” comes from the Old English words mistel (meaning dung) and tan (meaning twig). Early observers thought the plant grew from bird droppings, since mistletoe often popped up where birds perched. They weren’t far off – in the 1500s, botanists confirmed that birds do indeed spread the sticky seeds after a berry snack.

Despite its reputation as a mooch, mistletoe isn’t completely lazy; it is a hemiparasite. Its green leaves still photosynthesize – in other words, it makes some of its own food. It attaches itself to a tree using special roots called haustoria, which burrow just deep enough to “borrow” a drink without killing the host.

In winter, mistletoe puts on its holiday best: clusters of small, white, waxy berries that are mildly toxic to humans but irresistible to birds. After a snack, birds help spread the plant by wiping sticky seeds onto new branches … nature’s own version of tree-to-tree gift giving!

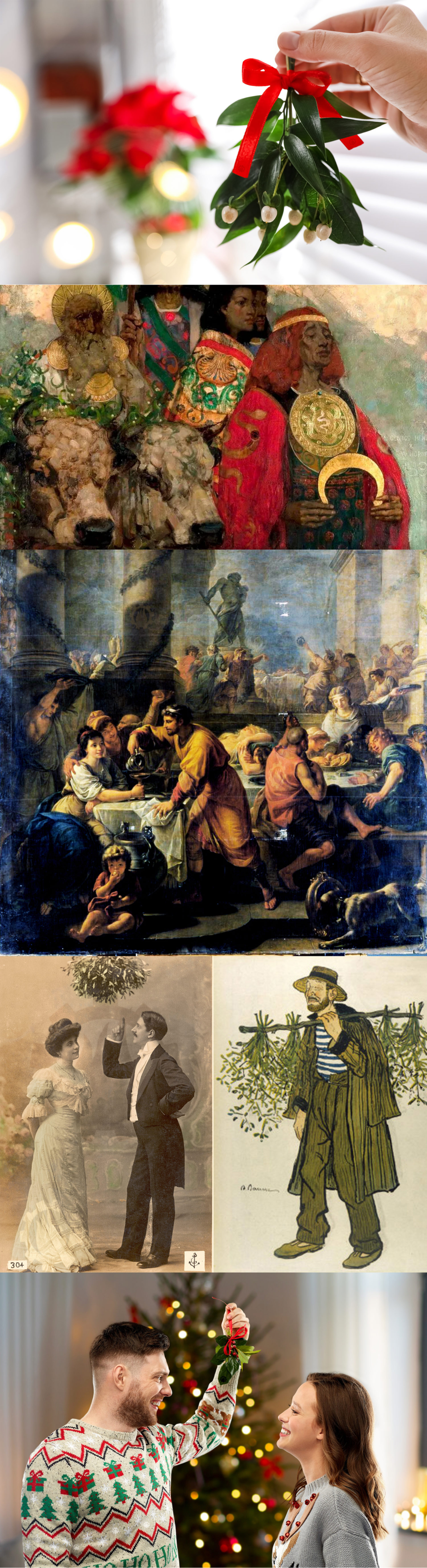

Long before mistletoe became a Christmas decoration, it was considered a sacred and mysterious plant by ancient civilizations. The earliest associations go back thousands of years to the Celtic Druids, Norse mythology, and early Romans.

Celtic Druids (circa 1st century BCE): The Druids regarded mistletoe as a symbol of life and fertility. Seemingly “rootless,” which gave it mystical significance as a plant that could live without touching the earth. During winter solstice ceremonies, Druids would cut mistletoe with a golden sickle, catching it before it hit the ground (as touching the earth was believed to drain its power). They used it in rituals for protection, healing, and blessing homes for the coming year.

Norse Mythology: The most famous legend involves Baldur, the god of light and purity. According to the myth, Baldur’s mother, Frigg, made every plant and creature promise not to harm her son – except mistletoe, which she overlooked. Loki, the trickster god, fashioned a spear or arrow from mistletoe, which killed Baldur. After his death, Frigg’s tears turned into white berries on the mistletoe, and she declared the plant a symbol of love and forgiveness, promising to kiss anyone who passed beneath it – the beginning of the “underkiss”. (I made up that word!)

Roman Saturnalia (around 200 BCE – 400 CE): During Saturnalia, the ancient Roman festival held in December, celebrating Saturn, the god of agriculture, mistletoe was used as a symbol of fertility and peace. Enemies meeting under mistletoe were said to lay down their arms and declare a truce.

The practice of kissing under mistletoe didn’t appear until 18th-century England, where it evolved during Christmas festivities. In Georgian England (1700s), mistletoe balls – bundles of greenery with mistletoe and ribbons – were hung in doorways at Christmas parties. It was customary for a man to steal a kiss from a woman standing beneath it. If she refused, it was considered bad luck. For each kiss, a berry was plucked from the mistletoe; when the berries were gone, so were the kisses.

By the Victorian era, the tradition was solidly romanticized as mistletoe became a symbol of holiday courtship. Charles Dickens, in The Pickwick Papers (1836), wrote of mistletoe kisses at Christmas gatherings, helping popularize the idea in both England and America. Illustrations from the mid-1800s often depicted young couples sharing a shy kiss under mistletoe, cementing it in popular culture as part of Christmas charm and merriment.

Here in the U.S., the most common Christmas mistletoe (Phoradendron serotinum) grows throughout the East and South, while the West is home to bigleaf mistletoe and desert mistletoe – the latter producing clusters of pink or red fruits that stand out dramatically against bare desert trees.

So, Next Time You Hang the Mistletoe… Remember that this little sprig carries centuries of myth, science, and symbolism. It’s a plant that steals a bit to give a lot – feeding birds, inspiring legends, and bringing people together (for at least one quick kiss). SMOOCH!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!