Things We Can Count On

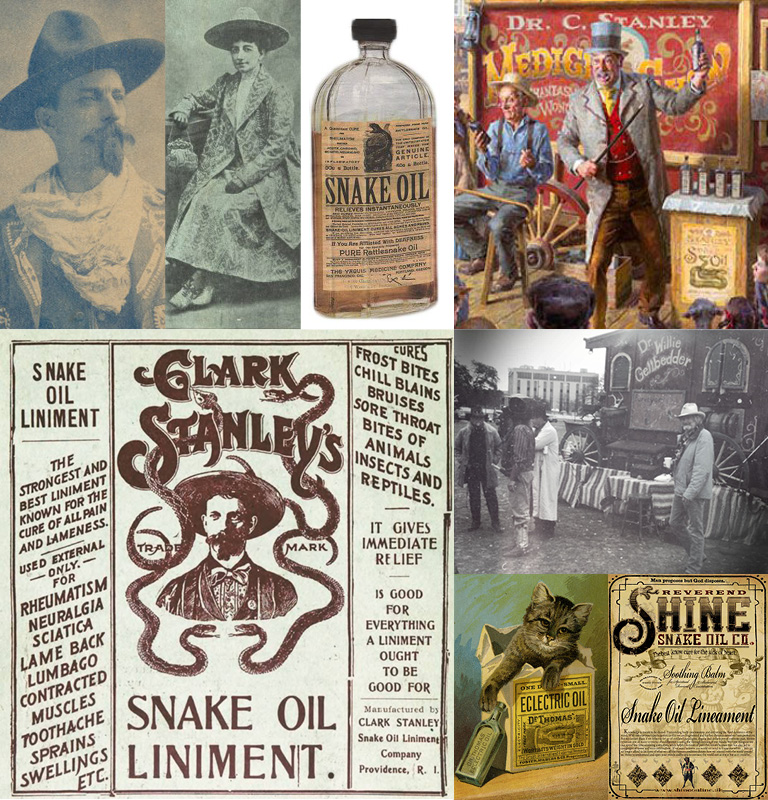

Clockwise starting at top left: Clark Stanley, Mrs. Clark Stanley in her rattlesnake suit (nice hat), Snake Oil bottle, a depiction of Clark Stanley in action, Others get in on the action: Dr. Willie Gellbedder’s wagon, an ad from the Reverend Shine Snake Oil Co., Dr. Thomas Electric Oil (whaaaat? And what does a cat have to do with it?), Clark Stanley’s newspaper ad.

At KHT, we keep things pretty simple and traditional. Put in a hard day’s work. Be honest and straightforward with customers. Give our word and stand by it. And when looking someone in the eye, it’s ok to close an agreement with a nod, smile and a firm handshake. Seems pretty simple really. But lately there’s been so much noise about what’s “real”, what’s fake, who to trust, who to blame. I don’t know about you, but my inbox and online accounts seem flooded with articles and opinions around fake news, unmet promises and misinformation. Add to that all the clickbait, spam, and junk mail, and it’s a wonder we can navigate our workday at all. Recently I saw an ad making all these crazy promises and thought “geez, that guy seems like a snake oil salesman.” Which got me to thinking, where did that term come from. Like I often do, I turned to the internet, and found some recaps of the backstory, a delightful marketing tale that includes a cowboy, a socialist, and Teddy Roosevelt. Enjoy.

In 1893, the world turned its eyes to Chicago, when the city hosted the Chicago World’s Fair, a spectacle seen by 27 million people over six months. Big brands were launched like Juicy Fruit gum, Cream of Wheat and Pabst Blue Ribbon beer.

In the middle of that pageantry was a self-described cowboy and “Rattlesnake King” by the name of Clark Stanley. He had rolled into town to sell one thing to the revelers at the Fair: Snake Oil, and he did so with great fanfare and showmanship, deftly grabbing rattlesnakes from his bag, slicing them open, and dropping them into a great vat of boiling water. As the snake’s fat rose to the top, he skimmed it off, mixed it with a concoction of patented ingredients, bottled it, and sold it in .50 bottles as Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment –“Good for Everything a Liniment Ought to Be Good For”.

Long before it became synonymous with quackery, snake oil was a real medicinal substance that was potentially effective. The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad in the 1800s brought thousands of Chinese immigrants to the American West and Pacific Coast, and they brought many traditional medical remedies with them, including snake oil, made from the Chinese water snake, rich in omega-3 fatty acids, a potent anti-inflammatory agent.

According to Stanley, he spent years conquering the West—conquests he detailed in pamphlets that also happened to serve as advertisements for his Snake Oil Liniment – (how’s that for “content marketing”?). claiming he learned of the powers of snake oil for medicinal purposes from the Hopi people, recounting tales of “snake dancers” who stared deadly rattlesnakes in the face without fear. Business was booming.

Eventually, he met a druggist from Boston who convinced him to move east and open a manufacturing facility to sell his product in bulk. A newspaper interview recounted how Stanley fearlessly handled the snakes in his Massachusetts office, telling the reporter how he makes the liniment over the winter, then spends the rest of the year traveling from town to town with his family to sell it.

Around 1901, Stanley moved his headquarters to an even larger facility in Rhode Island, still printing his cowboy tales in pamphlets, always accompanied by ads for his product. But in five short years, a book would be published by a socialist activist that would lead to the end of Stanley’s growing business.

In the early 1900s, a socialist author, Upton Sinclair, (remember your 7th grade history class?) went undercover in Chicago’s stockyards to investigate the exploitation of poor immigrant workers at the hands of the powerful meatpacking businesses. He described in his work called “The Jungle” the long hours, dangerous work conditions, wage theft, and predatory lenders who preyed on a Lithuanian family who had come to America in search of a better life. The work was republished as a book the next year and became a runaway hit. The public was shocked and outraged.

The public outcry—and the endless barrage of letters from Sinclair himself—was enough to force Teddy Roosevelt (who had previously described Sinclair as a “crackpot”) and his administration to pass two important pieces of legislation: The Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, a measure that caused a big problem for Clark Stanley and his snake oil.

With the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act, the government finally had some teeth with which to crack down on hucksters of phony “patent medicines.” (the Act would later evolve into the modern day Food and Drug Administration). While other laws had provided some protections, the Act defined “misbranding” and “adulteration” for the first time—stating that a drug would violate the law if it is “falsely labeled in any respect.”

It took another decade for the government to catch up to Clark Stanley, but in 1916, a shipment of his Snake Oil Liniment was seized by the District Attorney and tested by the Bureau of Chemistry. They found Stanley’s miracle cure was nothing more than mineral oil, 1% fatty oil (probably beef fat), capsicum, and a trace amount of camphor and turpentine. Not a drop of snake oil to be found.

The D.A. took issue with the claimed uses on the bottle, and concluded that Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment was misbranded. Their decision did not mince words:

“The article was misbranded for the reason that certain statements, appearing on the label…and included in the booklet accompanying it, falsely and fraudulently represented it as a remedy for all pain and lameness, for rheumatism, neuralgia, sciatica, sprains, bunions, and sore throat, for bites of animals and reptiles, for all pains and aches in flesh, muscle and joints, as a relief for tic douloureux, and as a cure for partial paralysis of the arms and of the lower limbs, and as a remedy for paralysis and effective to reduce enlarged joints to their natural size, as a perfect antidote to pain and inflammation, and effective to kill the poison from bites of animals, insects or reptiles, and heal the wounds resulting from bites of animals, insects, or reptiles, when, in truth and in fact, it was not.”

On June 15th of that year, Clark Stanley pleaded no contest to the charges, and was fined $20, the equivalent of $459.27 today.

After several amendments, the Act eventually became the FDA, a powerful government office today with a $4 billion annual budget, charged with protecting the health and safety of Americans. The formation of the FDA was part of a larger movement—the “Progressive Era”—that saw a push towards more protections for consumers against unfair business practices. In 1914, the Federal Trade Commission was formed, which would be responsible for enforcing false advertising laws, preventing other businesses beyond the food and drug industry from misbranding their products.

Apparently, the Rattlesnake King didn’t find the truth to be all that profitable, because he disappeared after 1916. Historians don’t even know if Clark Stanley was his real name, or whether it was simply a stage name for his snake-wrangling cowboy persona.

What is known is that the term “snake oil” took on a life of its own, becoming a catch-all term for fraud. The “Snake Oil Salesman” became a stock character in Western movies, and lives on today.