One If by Land…

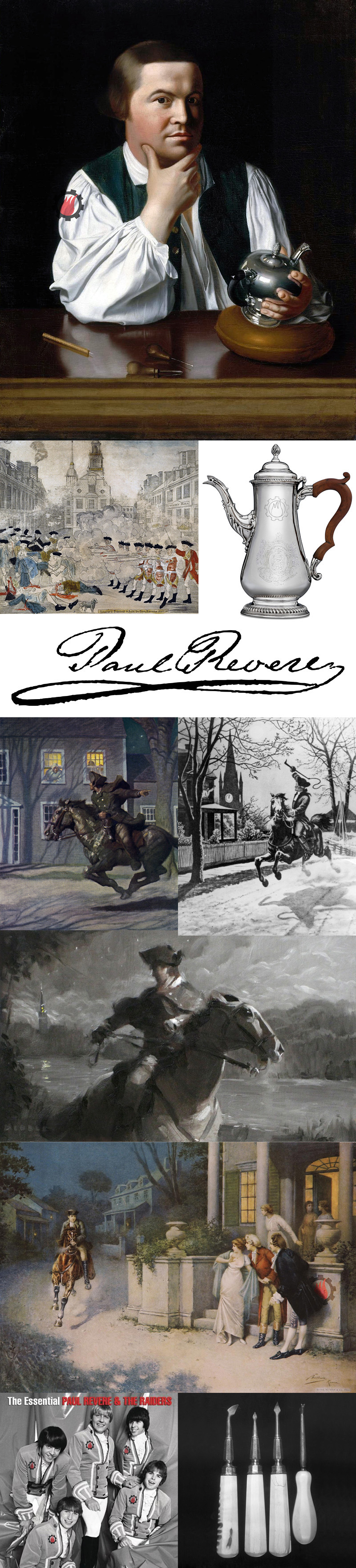

(top) Portrait of silversmith Paul Revere with one of his silver pieces by J. S. Copley. (row two l) An engraving by Paul Revere depicting the Boston Massacre. (row two r) Pre-Revolutionary War Paul Revere Silver Coffee Pot, circa 1775. (row three) Paul’s sig. (rows four – six) Some of the many paintings of Paul Revere. (bottom left) Paul Revere and the Raiders album cover, circa 1967. (bottom right) Paul was a dentist, too. He made his own dental instruments. That was 130 years before novocaine. Yikes!

Networking. Something that we’ve come quite accustomed to today. Whether it’s clicking your social media links, joining a conference call, logging in to a podcast, shouting across the shop floor or just visiting with friends at the local coffee shop, we all rely on networks to communicate, share information and keep ourselves up to date. History is filled with famous networks – from the cults of ancient Rome, to plotting European kings and queens, the silk rode of China, South American trading routes, Stalin’s secret police, the banking and investment industries, the Free Masons and of course modern-day Alibaba, Instagram and Twitter. Staying connected and getting news to the people changed when Guttenberg started pushing paper through his press and has now been overtaken by the immediacy of the internets. One network that is entwined in our American history is the famous ride of Paul Revere. Last weekend marked the anniversary of his 1775 ride through New England towns, supported by a network of lanterns, church bells and fellow riders. I absolutely love re-learning the history of our great country! Special thanks to Wikipedia and history.com for the insights and details. Enjoy the unique details below and be sure to turn your porch light on tonight in memory of his efforts.

- Paul Revere was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, and Patriot in the American Revolution. He is best known for his midnight ride to alert the colonial militia in April 1775 to the approach of British forces before the battles of Lexington and Concord.

- Revere was born in the North End of Boston on December 21, 1734. His father, a French Huguenot born Apollos Rivoire came to Boston at the age of 13 and was apprenticed to the silversmith John Coney. By the time he married Deborah Hitchborn, a member of a long-standing Boston family that owned a small shipping wharf, in 1729, Rivoire had anglicized his name to Paul Revere. Their son, Paul Revere, was the third of 12 children and eventually the eldest surviving son.

- Revere grew up in the environment of the extended Hitchborn family, and never learned his father’s native language. At 13 he left school and became an apprentice to his father. The silversmith trade afforded him connections with a cross-section of Boston society, which would serve him well when he became active in the American Revolution.

- Revere’s father died in 1754, when Paul was legally too young to officially be the master of the family silver shop. In February 1756, during the French and Indian War, he enlisted in the provincial army. Possibly he made this decision because of the weak economy, since army service promised consistent pay. Commissioned a second lieutenant in a provincial artillery regiment, he spent the summer at Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George in New York as part of an abortive plan for the capture of Fort St. Frédéric, but soon returned to run the family business.

- Revere’s business began to suffer when the British economy entered a recession in the years following the Seven Years’ War and declined further when the Stamp Act of 1765 resulted in a further downturn in the Massachusetts economy. Business was so poor that an attempt was made to attach his property in late 1765. To help make ends meet he even took up dentistry, a skill set he was taught by a practicing surgeon who lodged at a friend’s house. One client was Doctor Joseph Warren, a local physician and political opposition leader with whom Revere formed a close friendship. Revere and Warren, in addition to having common political views, were also both active in the same local Masonic lodges.

- Although Revere was not one of the “Loyal Nine”—organizers of the earliest protests against the Stamp Act—he was well connected with its members, who were laborers and artisans. Revere did not participate in some of the more raucous protests, such as the attack on the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. In 1765, a group of militants who would become known as the “Sons of Liberty” formed, of which Revere was a member. From 1765 on, in support of the dissident cause, he produced engravings and other artifacts with political themes. Among these engravings are a depiction of the arrival of British troops in 1768 (which he termed “an insolent parade”) and a famous depiction of the March 1770 Boston Massacre.

- In 1770 Revere purchased a house on North Square in Boston’s North End. Now a museum, the house provided space for his growing family while he continued to maintain his shop at nearby Clark’s Wharf. His wife Sarah died in 1773, and on October 10 of that year, Revere married Rachel Walker (1745–1813). They had eight children, three of whom died young.

- In November 1773 the merchant ship Dartmouth arrived in Boston harbor carrying the first shipment of tea made under the terms of the Tea Act. This act authorized the British East India Company to ship tea directly to the colonies, bypassing colonial merchants. Passage of the act prompted calls for renewed protests against the tea shipments, on which Townshend duties were still levied. Revere and Warren, as members of the informal North End Caucus, organized a watch over the Dartmouth to prevent the unloading of the tea. Revere took his turns on guard duty and was one of the ringleaders in the Boston Tea Party of December 16, when colonists, some disguised as Indians, dumped tea from the Dartmouth and two other ships into the harbor.

- From December 1773 to November 1775, Revere served as a courier for the Boston Committee of Public Safety, traveling to New York and Philadelphia to report on the political unrest in Boston. Research has documented 18 such rides. In 1774, his cousin John on the island of Guernsey wrote to Paul that John had seen reports of Paul’s role as an “express” courier in London newspapers.

- In 1774, the military governor of Massachusetts, General Thomas Gage, dissolved the provincial assembly on orders from Great Britain, closed the port of Boston and all over the city forced private citizens to quarter (provide lodging for) soldiers in their homes.

- During this time, Revere and a group of 30 “mechanics” began meeting in secret at his favorite haunt, the Green Dragon, to coordinate the gathering and dissemination of intelligence by “watching the Movements of British Soldiers”. Around this time Revere regularly contributed politically charged engravings he made at his silversmith shop to the recently founded Patriot monthly, Royal American Magazine.

- He rode to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in December 1774 upon rumors of an impending landing of British troops there, a journey known in history as the Portsmouth Alarm. Although the rumors were false, his ride sparked a rebel success by provoking locals to raid Fort William and Mary, defended by just six soldiers, for its gunpowder supply.

- When British Army activity on April 7, 1775, suggested the possibility of troop movements, Joseph Warren sent Revere to warn the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, then sitting in Concord, the site of one of the larger caches of Patriot military supplies. After receiving the warning, Concord residents began moving the military supplies away from the town.

- One week later, on April 14, General Gage received instructions from Secretary of State William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth, to disarm the rebels, who were known to have hidden weapons in Concord, among other locations, and to imprison the rebellion’s leaders, especially Samuel Adams and John Hancock.

- Dartmouth gave Gage considerable discretion in his commands, issuing orders to Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith to proceed from Boston “with utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy… all Military stores…. But you will take care that the soldiers do not plunder the inhabitants or hurt private property.” Gage did not issue written orders for the arrest of rebel leaders, as he feared doing so might spark an uprising.

- Between 9 and 10 p.m. on the night of April 18, 1775, Joseph Warren told Revere and William Dawes that the king’s troops were about to embark in boats from Boston bound for Cambridge and the road to Lexington and Concord. Warren’s intelligence suggested that the most likely objectives of the regulars’ movements later that night would be the capture of Adams and Hancock. They did not worry about the possibility of regulars marching to Concord, since the supplies at Concord were safe, but they did think their leaders in Lexington were unaware of the potential danger that night. Revere and Dawes were sent out to warn them and to alert colonial militias in nearby towns.

- In the days before April 18, Revere had instructed Robert Newman, the sexton of the North Church, to send a signal by lantern to alert colonists in Charlestown as to the movements of the troops when the information became known. In what is well known today by the phrase “one if by land, two if by sea”, one lantern in the steeple would signal the army’s choice of the land route while two lanterns would signal the route “by water” across the Charles River (the movements would ultimately take the water route, and therefore two lanterns were placed in the steeple).

- Revere first gave instructions to send the signal to Charlestown. He then crossed the Charles River by rowboat, slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset at anchor. Crossings were banned at that hour, but Revere safely landed in Charlestown and rode to Lexington, avoiding a British patrol and later warning almost every house along the route. The Charlestown colonists dispatched additional riders to the north.

- Riding through present-day Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Revere warned patriots along his route, many of whom set out on horseback to deliver warnings of their own. By the end of the night there were probably as many as 40 riders throughout Middlesex County carrying the news of the army’s advance.

- Revere did not shout the phrase later attributed to him (“The British are coming!”): his mission depended on secrecy, the countryside was filled with British army patrols, and most of the Massachusetts colonists (who were predominantly English in ethnic origin) still considered themselves British. Revere’s warning, according to eyewitness accounts of the ride and Revere’s own descriptions, was “The Regulars are coming out.”

- Revere arrived in Lexington around midnight, with Dawes arriving about a half-hour later. They met with Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were spending the night with Hancock’s relatives (in what is now called the Hancock–Clarke House), and they spent a great deal of time discussing plans of action upon receiving the news. They believed that the forces leaving the city were too large for the sole task of arresting two men and that Concord was the main target. The Lexington men dispatched riders to the surrounding towns, and Revere and Dawes continued along the road to Concord accompanied by Samuel Prescott, a doctor who happened to be in Lexington “returning from a lady friend’s house at the awkward hour of 1 a.m.”

- Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British Army patrol in Lincoln at a roadblock on the way to Concord. Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods; he eventually reached Concord. Dawes also escaped, though he fell off his horse not long after and did not complete the ride.

- Revere was captured and questioned by the British soldiers at gunpoint. He told them of the army’s movement from Boston, and that British army troops would be in some danger if they approached Lexington, because of the large number of hostile militia gathered there. He and other captives taken by the patrol were still escorted east toward Lexington, until about a half mile from Lexington they heard a gunshot. The British major demanded Revere explain the gunfire, and Revere replied it was a signal to “alarm the country”.

- As the group drew closer to Lexington, the town bell began to clang rapidly, upon which one of the captives proclaimed to the British soldiers “The bell’s a’ringing! The town’s alarmed, and you’re all dead men!”. The British soldiers gathered and decided not to press further towards Lexington but instead to free the prisoners and head back to warn their commanders. The British confiscated Revere’s horse and rode off to warn the approaching army column. Revere walked to Rev. Jonas Clarke’s house, where Hancock and Adams were staying. As the battle on Lexington Green unfolded, Revere assisted Hancock and his family in their escape from Lexington, helping to carry a trunk of Hancock’s papers.

- The ride of the three men triggered a flexible system of “alarm and muster” that had been carefully developed months before, in reaction to the colonists’ impotent response to the Powder Alarm of September 1774. This system was an improved version of an old network of widespread notification and fast deployment of local militia forces in times of emergency. The colonists had periodically used this system all the way back to the early years of Indian wars in the colony, before it fell into disuse in the French and Indian War.

- In addition to other express riders delivering messages, bells, drums, alarm guns, bonfires, and a trumpet were used for rapid communication from town to town, notifying the rebels in dozens of eastern Massachusetts villages that they should muster their militias because the regulars in numbers greater than 500 were leaving Boston with possible hostile intentions. This system was so effective that people in towns 25 miles from Boston were aware of the army’s movements while they were still unloading boats in Cambridge. Unlike in the Powder Alarm, the alarm raised by the three riders successfully allowed the militia to confront the British troops in Concord, and then harry them all the way back to Boston.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow popularized Paul Revere in The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, a poem first published in 1863 as part of Tales of a Wayside Inn.

- Revere’s friend and compatriot Joseph Warren was killed in the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. Because soldiers killed in battle were often buried in mass graves without ceremony, Warren’s grave was unmarked. On March 21, 1776, several days after the British army left Boston, Revere, Warren’s brothers, and a few friends went to the battlefield and found a grave containing two bodies. After being buried for nine months, Warren’s face was unrecognizable, but Revere was able to identify Warren’s body because he had placed a false tooth in Warren’s mouth and recognized the wire he had used for fastening it. Warren was given a proper funeral and reburied in a marked grave.

- After the war, Revere developed advanced manufacturing for gunpowder, mastered the iron casting process and realizing substantial profits from this new product line. Revere identified a burgeoning market for church bells in the religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening that followed the war. Beginning in 1792 he became one of America’s best-known bell casters, working with sons Paul Jr. and Joseph Warren Revere in the firm Paul Revere & Sons. This firm cast the first bell made in Boston and ultimately produced hundreds of bells, a number of which remain in operation to this day.

- In 1794, Revere decided to take the next step in the evolution of his business, expanding his bronze casting work by learning to cast cannon for the federal government, state governments, and private clients. Although the government often had trouble paying him on time, its large orders inspired him to deepen his contracting and seek additional product lines of interest to the military.

- Revere remained politically active throughout his life. His business plans in the late 1780s were often stymied by a shortage of adequate money in circulation. Alexander Hamilton’s national policies regarding banks and industrialization exactly matched his dreams, and he became an ardent Federalist committed to building a robust economy and a powerful nation. Of particular interest to Revere was the question of protective tariffs; he and his son sent a petition to Congress in 1808 asking for protection for his sheet copper business. He continued to participate in local discussions of political issues even after his retirement and circulated a petition offering the government the services of Boston’s artisans in protecting Boston during the War of 1812.

- Revere died on May 10, 1818, at the age of 83, at his home on Charter Street in Boston. He is buried in the Granary Burying Ground on Tremont Street.

- After Revere’s death, the family business was taken over by his oldest surviving son, Joseph Warren Revere. The copper works founded in 1801 continues today as the Revere Copper Company, with manufacturing divisions in Rome, New York and New Bedford, Massachusetts.

- The song “Me and Paul Revere”, written by musician Steve Martin and performed with his bluegrass group Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers, was inspired by the tale of Paul Revere’s ride and told from the point of view of Revere’s horse, Brown Beauty.

If you are intrigued by “networks” throughout history and up to the present day, be sure to read Niall Ferguson’s latest book, The Square and the Tower, Penguin Press 2018.

Hmmmmmm…

Hey, check it out. Jack Black looks a whole lot like Paul Revere.

And for your listening pleasure…

>> Steve Martin ‘Me and Paul Revere’ (lyrics from the perspective of Paul’s horse)

>> Paul Revere and The Raiders – Kicks 1967