I had a dream the other night after finishing this week’s blog post. I combined my love of beer with my love for my logo. I know, crazy right? Anyhow, any bar, restaurant, or back yard party I went to, people were drinking my beer… And loving it!!!!! So I had some mockups made of the bottle label from my dream and put them on a brown bottle and a green bottle. (I like the brown bottle.) Then I thought I’d have different colored bottle caps for the different types of beers: Ales, Stout, Wheat, Lager, Porter, etc. And in my dream I had 14 beer & brats trucks to go to local fairs and other events!! Ha!!! Not only that, I had a fleet of tankers that look like beer cans transporting my beers all over the country. Cool, huh. Then there’s my beer taster, Dingo. Nothing goes out the door unless Dingo says so. (Dingo also protects the beer recipes.) Whacky dream, right? But so much fun. What do you think of the beer’s name in my dream: “Kowalski’s World Famous Brewskis”? Should I make this a beer brand?? Let me know. I’m tempted…really tempted. And now I’m really thirsty. And really hungry. :)))

A little song to get you in the mood to read on.

Now that I have “both my shots”, I thought it would finally be fun to get out a bit and reconnect with some of my good friends. (I hope this is something you all are doing as well). After many text message exchanges, we decided to get our “boy’s” group (Actually, we call it our “playgroup”!) together. You are never too old to have a great playgroup! We decided to get in an early season round of golf. Challenged by the NE Ohio weather, we caught a brisk, bright sunny day and enjoyed “knocking” the ball around (some good pars, bogies, doubles and yes, some not so good “snowmen”) Talk about a PIA (pain in the @%$) Job! All told, I have to admit – it was a blast. Not having the opportunity to visit together for almost a year, we wrapped up our round and met in the clubhouse afterwards to share some good laughs about our “flog” while catching up on family, kids, grandkids, work, “jabs” and more. For those of you who understand golf, our “19th hole” of course included having a snack or two (or three) and a fresh, cool draft beverage. Our attentive waitress passed around a menu filled with dozens of beer choices – light, dark, lagers, stouts, ales, porters, IPA’s – oh my! Perhaps it was the setting, or the fun of seeing friends, but I must admit, my selection was immediately refreshing and delicious. It got me to thinking about why we still have beer as a beverage option and how popular this truly ancient beverage still is today. I went exploring online and found some cool info on the history and early regulations of beer. With so much history to write about, I picked some of my favorite nuggets to share, with lots of links to help you dig deeper. Thanks to Wikipedia, NPR & heinonline.com. Enjoy, and next time on the links, be sure to finish up with a “cold one” and think of your buds at KHT.

- Beer is one of the oldest drinks humans have produced. The first chemically confirmed barley beer dates back to the 5th millennium BC in Iran and was recorded in the written history of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia before spreading throughout the world. Ancient Chinese artifacts suggest that beer was brewed with grapes, honey, hawthorns, and rice and produced as far back as 7,000 BC. (wonder if they played golf too??).

- In Mesopotamia, the oldest evidence of beer is believed to be a 6,000-year-old Sumerian tablet depicting people consuming a drink through reed straws from a communal bowl. A 3,900-year-old Sumerian poem honoring Ninkasi, the patron goddess of brewing (of course there is a beer goddess!), contains the oldest surviving beer recipe, describing the production of beer from bread made from barley.

- Beer became vital to all the grain-growing civilizations of Eurasian and North African antiquity, including Egypt—so much so that in 1868 James Death put forward a theory in The Beer of the Bible that the manna from heaven that God gave the Israelites was a bread-based, porridge-like beer called wusa. These beers were often thick, more of a gruel than a drink, and drinking straws were used by the Sumerians to avoid the bitter solids left over from fermentation.

- Though beer was drunk in Ancient Rome, it was replaced in popularity by wine. Tacitus wrote disparagingly of the beer brewed by the Germanic peoples of his day. Their name for beer was brutos, or brytos. The Romans called their brew cerevisia, from the Celtic word for it.

- It was discovered early that reusing the same container for fermenting the mash would produce more reliable results, so brewers on the move carried their tubs with them.

- Beer was part of the daily diet of Egyptian pharaohs, made from baked barley bread, and was also used in religious practices. During the building of the Great Pyramids in Giza, Egypt, each worker got a daily ration of four to five liters of beer, which served as both nutrition and refreshment that was crucial to the pyramids’ construction. (Beer as nutrition – wonder if Jackie will buy that one??)

- In 450BCE, Greek writer Sophocles discussed the concept of moderation when it came to consuming beer in Greek culture, and believed that the best diet for Greeks consisted of bread, meats, various types of vegetables, and beer (obvious these guys were golfers too!).

- The use of hops in beer was written of in 822 by the Carolingian Abbot Adalard of Corbie. Flavoring beer with hops was known at least since the 9th century. Hopped beer was perfected in the medieval towns of Bohemia by the 13th century. German towns pioneered a new scale of operation with standardized barrel sizes that allowed for large-scale export.

- The use of hops spread to the Netherlands and then to England. In 15th century England, an unhopped beer would have been known as an ale, while the use of hops would make it a beer. Hopped beer was imported to England from the Netherlands as early as 1400 in Winchester, and hops were being planted on the island by 1428.

- On this day, April 23,1516, William IV, Duke of Bavaria, adopted the Reinheitsgebot (purity law), perhaps the oldest food regulation still in use through the 20th century. The Gebot ordered that the ingredients of beer be restricted to water, barley, and hops.

- Yeast was added to the list after Louis Pasteur‘s discovery in 1857. To this day, the Gebot is considered a mark of purity in beers, although this is controversial.

- Recently excavated tombs indicate that the Chinese brewed alcoholic drinks from both malted grain and grain converted by mold from prehistoric times, (the resulting molded rice being (called Jiǔ qū in Chinese and Koji in Japanese)

- Some Pacific island cultures ferment starch that has been converted to fermentable sugars by human saliva, similar to the chicha of South America. This practice is also used by many other tribes around the world, who either chew the grain and then spit it into the fermentation vessel or spit into a fermentation vessel containing cooked grain, which is then sealed up for the fermentation. Enzymes in the spittle convert the starch into fermentable sugars, which are fermented by wild yeast. Whether or not the resulting product can be called beer is sometimes disputed, but I’m guessing my foursome would pass on my “spittle” beer!

- Asia’s first brewery was incorporated in 1855 (although it was established earlier) by Edward Dyer at Kasauli in the Himalayan Mountains in India under the name Dyer Breweries. The company still exists and is known as Mohan Meakin, today comprising a large group of companies across many industries.

- The hydrometer transformed how beer was brewed. Before its introduction beers were brewed from a single malt: brown beers from brown malt, amber beers from amber malt, pale beers from pale malt. Using the hydrometer, brewers could calculate the yield from different malts. They observed that pale malt, though more expensive, yielded far more fermentable material than cheaper malts.

- The invention of the drum roaster in 1817 by Daniel Wheeler allowed for the creation of very dark, roasted malts, contributing to the flavor of porters and stouts. Its development was prompted by a British law of 1816 forbidding the use of any ingredients other than malt and hops. Porter brewers, employing a predominantly pale malt grist, urgently needed a legal colourant. Wheeler’s patent malt was the solution.

- In 1912, the use of brown bottles began to be used by Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin in the U.S. This innovation has since been accepted worldwide and prevents harmful rays from destroying the quality and stability of beer.

- Modern breweries now brew many types of beer, ranging from ancient styles such as the spontaneously-fermented lambics of Belgium; the lagers, dark beers, wheat beers and more of Germany; the UK’s stouts, milds, pale ales, bitters, golden ale and new modern American creations such as chili beer, cream ale, and double India pale ales.

- Today, the brewing industry is a huge global business, consisting of several multinational companies, and many thousands of smaller producers ranging from brewpubs to regional breweries. Advances in refrigeration, international and transcontinental shipping, marketing and commerce have resulted in an international marketplace, where the consumer has literally hundreds of choices between various styles of local, regional, national and foreign beers.

- From my personal research, beer goes good with pretzels, chips, dip, crackers, pizza, wings, hot dogs, burgers, steak, spaghetti, cheese dip, nachos …. You?

Beer Mythology includes:

- The Finnish epic Kalevala, collected in written form in the 19th century but based on oral traditions many centuries old, devotes more lines to the origin of beer and brewing than it does to the origin of mankind.

- The mythical Flemish king Gambrinus (from Jan Primus (John I)), is sometimes credited with the invention of beer.

- According to Czech legend, deity Radegast, god of hospitality, invented beer.

- Ninkasi was the patron goddess of brewing in ancient Sumer.

- The immense blood-lust of the fierce lioness Egyptian goddess Sekhmet was only sated after she was tricked into consuming an extremely large amount of red-colored beer (believing it to be blood): she became so drunk that she gave up slaughter altogether and became docile.

- In Norse mythology the sea god Ægir, his wife Rán, and their nine daughters, brewed ale (or mead) for the gods. In the Lokasenna, it is told that Ægir would host a party where all the gods would drink the beer he brewed for them. He made this in a giant kettle that Thor had brought. The cups in Ægir’s hall were always full, magically refilling themselves when emptied. Ægir had two servants in his hall to assist him; Eldir [Fire-Kindler] and Fimafeng [Handy].

- Recent Irish Mythology attributes the invention of beer to fabled Irishman Charlie Mops.

|

| How does he do it???????

|

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

DO YOU LIKE CONTESTS?

Me, too.

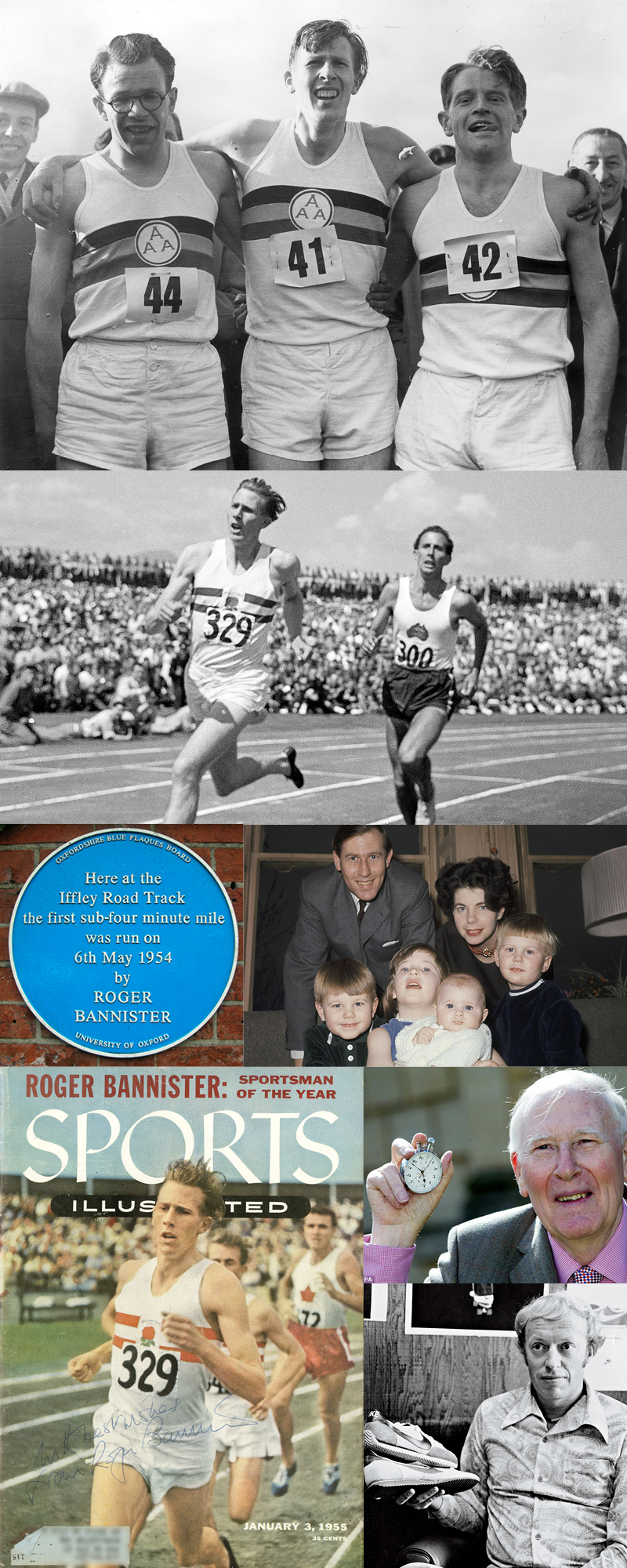

As you may know the Kowalski Heat Treating logo finds its way

into the visuals of my Friday posts.

I. Love. My. Logo.

One week there could be three logos.

The next week there could be 15 logos.

And sometimes the logo is very small or just a partial logo showing.

But there are always logos in some of the pictures.

So, I challenge you, my beloved readers, to count them and send me a

quick email with the total number of logos in the Friday post.

On the following Tuesday I’ll pick a winner from the correct answers

and send that lucky person some great KHT swag.

So, start counting and good luck!

Oh, and the logos at the very top header don’t count.

Got it? Good. :-))))

Have fun!!

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::