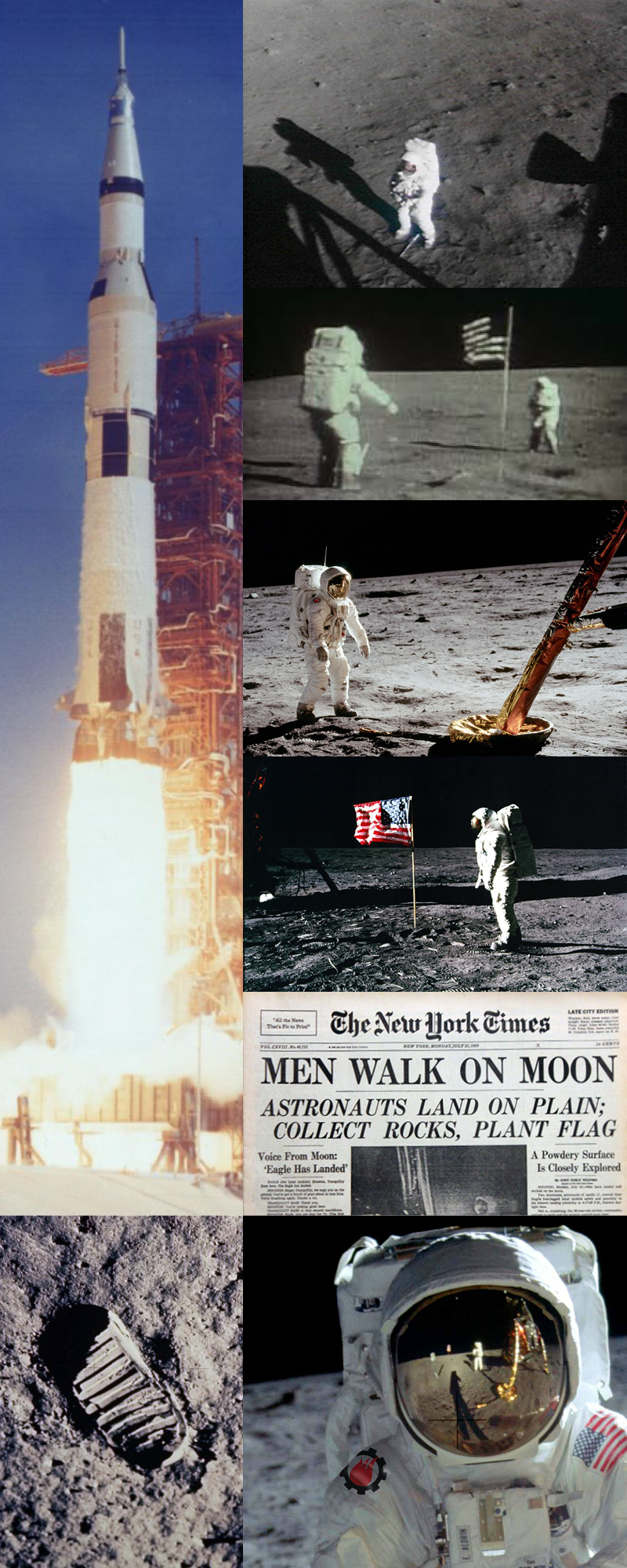

On July 20

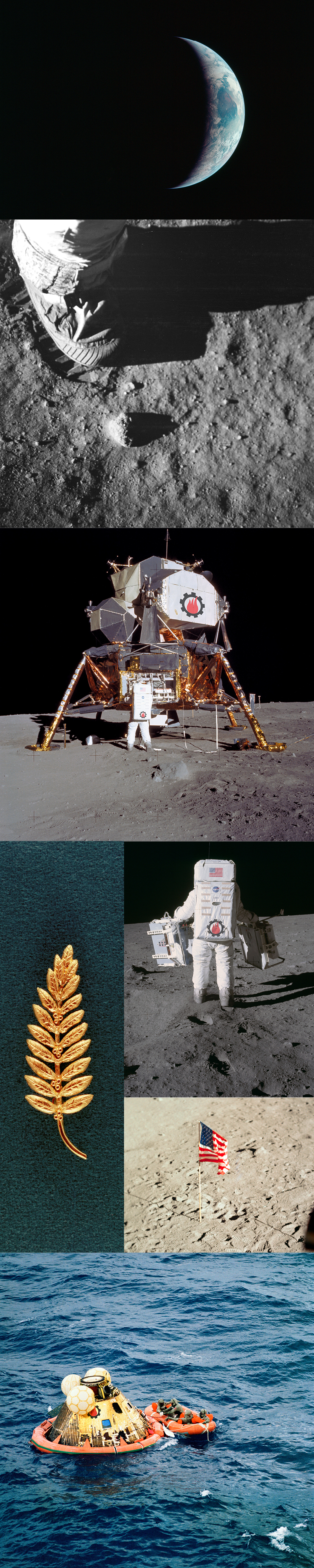

(top) Earth sweet earth; (row two) You know that image that everyone has seen again and again of the footprint on the moon? Well, this is what it looked like before he got his foot out of the way; (row three) Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., lunar module pilot, prepares to deploy the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package; (row four left) The gold replica of an olive branch, the traditional symbol of peace, which was left on the moon’s surface by Apollo 11 crewmembers. It is less than half a foot in length. The gesture represents a fresh wish for peace for all mankind; (row four, top right) Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. moves to deploy two components of the Scientific Experiments. The Passive Seismic Experiments Package is in his left hand and in his right hand is the Laser Ranging Retro-Reflector. Neil Armstrong took this photograph with a 70mm lunar surface camera; (row four, bottom right) Our wonderful flag (with all of the footprints) planted on the moon! Are you kidding!!! (bottom) The Apollo 11 crew await pickup by a helicopter from the USS Hornet. They splashed down at 11:49 a.m. (CDT), July 24, 1969, about 812 nautical miles southwest of Hawaii and only 12 nautical miles from the USS Hornet. Wow!! God Bless America!!!

Talk about a PIA (Pain in the @%$) Job! When the President of the United States gives you a project, never before attempted, you accept. And then set out to accomplish the greatest event in history. Given all the space specials and history news this week, you probably know tomorrow marks the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Lunar Landing. With so many amazing problem-solving solutions that had to come together, it’s tough to find them all. A task this big, with no past history, is simply unheard of – but we did it. My team solves PIA (Pain in the @%$) jobs each and every day. When I explored deeper into the history of Apollo 11 I was amazed and humbled at the dedication of this previous generation. All of us Americans should /can be so proud of their accomplishments and know that together there is nothing we in these wonderful United States can’t solve together! Here is some fun trivia from the mission. Enjoy! And special thanks to NASA, Smithsonian, cnet, and Wikipedia.

The ultimate PIA (pain in the @%$ Job(s)! – On May 25, 1961, when Kennedy asked Congress to send Americans to the Moon before the 1960s were over, NASA had no rockets to launch astronauts to the Moon, no computer portable enough to guide a spaceship to the Moon, no spacesuits to wear on the way, no spaceship to land astronauts on the surface (let alone a Moon car to let them drive around and explore), no network of tracking stations to talk to the astronauts en route, no Mission Control, no nutrition plan, no multi-gravity food – in essence we didn’t even know what was needed.

Our unpreparedness for the task goes a level deeper: We didn’t even know how to fly to the Moon. We didn’t know what course to fly to get there from here. And as the small example of lunar dirt shows, we didn’t know what we would find when we got there. Physicians worried that people wouldn’t be able to think in micro-gravity conditions. Mathematicians worried that we wouldn’t be able to calculate how to rendezvous two spacecraft in orbit—to bring them together in space and dock them in flight both perfectly and safely.

Ten thousand problems had to be solved to get us to the Moon. Every one of those challenges was tackled and mastered between May 1961 and July 1969. The astronauts, the nation, flew to the Moon because hundreds of thousands of scientists, engineers, managers and factory workers unraveled a series of puzzles, often without knowing whether the puzzle had a good solution.

Here are just some of the PIA Jobs that were solved:

- That computer navigated through space and helped the astronauts operate the ship. But the astronauts also traveled to the Moon with paper star charts so they could use a sextant to take star sightings—like 18th-century explorers on the deck of a ship—and cross-check their computer’s navigation.

- The software of the computer was stitched together by women sitting at specialized looms—using wire instead of thread.

- The heat shield was applied to the spaceship by hand with a fancy caulking gun;

- The parachutes were sewn by hand, and then folded by hand. The only three staff members in the country who were trained and licensed to fold and pack the Apollo parachutes were considered so indispensable that NASA officials forbade them to ever ride in the same car, to avoid their all being injured in a single accident.

- Three times as many people worked on Apollo as on the Manhattan Project to create the atomic bomb. In 1961, the year Kennedy formally announced Apollo, NASA spent $1 million on the program for the year. Five years later NASA was spending about $1 million every three hours on Apollo, 24 hours a day.

- The LM was, in fact, perhaps the strangest flying craft ever created. It was the first, and remains the only, manned spacecraft designed solely for use off Earth. It would never have to fly through an atmosphere, so it didn’t need the structural robustness that would require.

- The lunar module’s other significant challenge was that it could never be test-flown before being used for its critical role. There’s no place on Earth to take a spaceship designed for flight in a zero-gravity vacuum and fly it around. So the people who would pilot the lunar modules to the Moon never practiced flying them, except in simulators, which were designed and built by people who had never flown a lunar module.

- For the first Moonwalk ever, Sonny Reihm was inside NASA’s Mission Control building, watching every move on the big screen. Reihm was a supervisor for the most important Moon technology after the lunar module itself: the spacesuits, the helmets, the Moonwalk boots. The spacesuits were the work of Playtex, the folks who brought America the “Cross Your Heart Bra” in the mid-1950s, a company with a lot of expertise developing clothing that had to be flexible as well as form-fitting. The suits were hand stitched marvels: 21 layers of nested fabric, strong enough to stop a micrometeorite, but still flexible enough for Aldrin’s kangaroo hops and quick cuts.

And here is some trivia about the mission:

- On July 20, 1969, an estimated 650 million people around the world watched the same televised image of an otherworldly sight. It’s an amazing number, based on the lack of cable, dish, the internet and global communications today.

- The American flag the Apollo 11 astronauts planted on the moon was manufactured by Sears, but NASA wanted that information kept secret.

- Tang. The powder-based orange drink from General Foods – ideal for consumption in a zero-gravity environment – soared to celebrity status in 1962 when Mercury astronaut John Glenn performed eating experiments while orbiting Earth aboard Friendship 7. Astronauts brought Tang on their missions and all manned space flights from 1965–1975.

- There’s a mystery surrounding Neil Armstrong’s famous quote. “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Fake news? Not exactly. Armstrong has always insisted that he said “one small step for a man,” not the widely quoted “one small step for man,” and the grainy NASA audio recordings don’t offer a definitive answer. Researchers from Michigan State University and Ohio State University set out to solve the mystery, and their findings seem to back up Armstrong’s assertion. They analyzed recordings of conversational speech from 40 people raised in Columbus, Ohio, near Armstrong’s hometown of Wapakoneta, and found that they typically blended the words “for a” so they sound like “frrr(uh)”.

- Your cellphone is more powerful than Apollo 11’s computers. While the Apollo Guidance Computer systems that powered Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins to the moon and back in July 1969 were cutting-edge for the time, they’re technologically primitive compared to the cell phones and smartwatches we use half a century later. Today’s Samsung Galaxy S10 Smartphone6, with its eight gigabytes of memory, is light years ahead of the Apollo 11’s computer, which propelled our fearless astronauts to the moon and back with only two kilobytes.

- Krispy Kreme doughnuts were served. This marketing ploy is not just empty calories: Krispy Kreme was at the launch of Apollo 11 in 1969, serving fresh doughnuts to Americans who had gathered to witness lift-off of this monumental mission.

- “The Eagle has landed,” is one of the most famous quotes in NASA history. It was named in honor of America’s national bird, while the mission’s command module, Columbia, was named after Columbiad, the giant canon that launched the moonship in Jules Verne’s novel From the Earth to the Moon.

- The Apollo’s Saturn rockets were packed with enough fuel to throw 100-pound shrapnel three miles, and NASA couldn’t rule out the possibility that they might explode on takeoff. NASA seated its VIP spectators three and a half miles from the launchpad.

- Drinking water was a fuel-cell by-product, but Apollo 11’s hydrogen-gas filters didn’t work, making every drink bubbly, making going to the bathroom troublesome.

- When Apollo 11’s lunar lander, the Eagle, separated from the orbiter, the cabin wasn’t fully depressurized, resulting in a burst of gas equivalent to popping a champagne cork. It threw the module’s landing four miles off-target.

- Pilot Neil Armstrong nearly ran out of fuel landing the Eagle, and many at mission control worried he might crash. Apollo engineer Milton Silveira, however, was relieved: His tests had shown that there was a small chance the exhaust could shoot back into the rocket as it landed and ignite the remaining propellant.

- The “one small step for man” wasn’t actually that small. Armstrong set the ship down so gently that its shock absorbers didn’t compress. He had to hop 3.5 feet from the Eagle’s ladder to the surface.

- The astronauts all carried Duro-brand felt-tip pens, and if not for these the mission would not have made it home. In the cramped environment, someone had broken off the switch to the circuit breaker that activated the ascent engine. This is where Aldrin had a flash of ingenuity. “Since it was electrical, I decided not to put my finger in, or use anything that had metal on the end. I had a felt-tipped pen in the shoulder pocket of my suit that might do the job. After moving the countdown procedure up by a couple of hours in case it didn’t work, I inserted the pen into the small opening where the circuit breaker switch should have been, and pushed it in; sure enough, the circuit breaker held. We were going to get off the moon, after all.”

- The toughest moonwalk task? Planting the flag. NASA’s studies suggested that the lunar soil was soft, but Armstrong and Aldrin found the surface to be a thin wisp of dust over hard rock. They managed to drive the flagpole a few inches into the ground and film it for broadcast, and then took care not to accidentally knock it over.

- A few minutes after Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong landed on the moon, fellow Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins remained in orbit. They sent a message back asking for a moment’s silence. In this time, Aldrin, an elder in his local Presbyterian Church, had a little communion ceremony of his own, reading scripture and taking the sacrament. “I ate the tiny Host and swallowed the wine. I gave thanks for the intelligence and spirit that had brought two young pilots to the Sea of Tranquility. It was interesting for me to think: The very first liquid ever poured on the moon, and the very first food eaten there, were the communion elements.”

- Along with the American flag, the Apollo 11 mission left behind a small collection of items. Among them were medallions honouring Russian cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, and Vladimir Komarov, both of whom died tragically. Komarov’s death is particularly shocking. The story goes that he knew he was probably going to die on the 1967 mission to put a man into Earth orbit. He didn’t back out, because Gagarin was his back-up and he didn’t want Gagarin to die.

- On their return to Earth, the three astronauts were brought back via Hawaii. On their entry, they had to be processed like any other traveler, filling out customs declarations. In the “Departure From” field, they simply wrote “Moon,” and declared the “moon dust” and “moon rock” as items they were bringing back into America.

- Life insurance premiums for a trip to the moon were well beyond the means of Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins. As a preemptive measure to take care of their loved ones if they didn’t come back, the astronauts signed hundreds of postal covers. If they did not return, their families could sell these signatures. Today, these signed postal covers occasionally show up in space memorabilia auctions, where they can sell for thousands of dollars.

- President Richard Nixon had a contingency speech lined up for if the mission failed, too. You can read it here.

- The Moon has a smell. It has no air, but it has a smell. Each pair of Apollo astronauts to land on the Moon tramped lots of Moon dust back into the lunar module—it was deep gray, fine-grained and extremely clingy—and when they unsnapped their helmets, Neil Armstrong said, “We were aware of a new scent in the air of the cabin that clearly came from all the lunar material that had accumulated on and in our clothes.” To him, it was “the scent of wet ashes.” To his crewmate Buzz Aldrin, it was “the smell in the air after a firecracker has gone off.

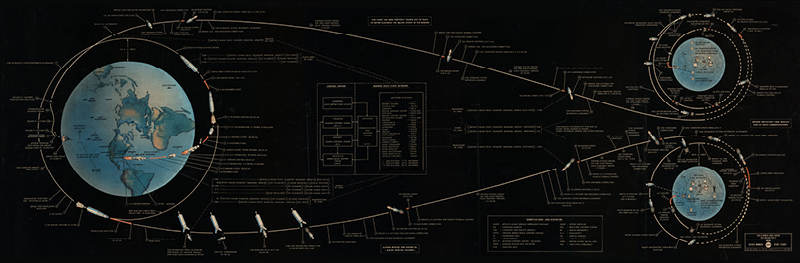

CLICK HERE to download this cool chart I found on the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s website. It shows the major events of the Apollo 11 mission from ignition to splashdown. Everything had to go absolutely right on this mega PIA job.

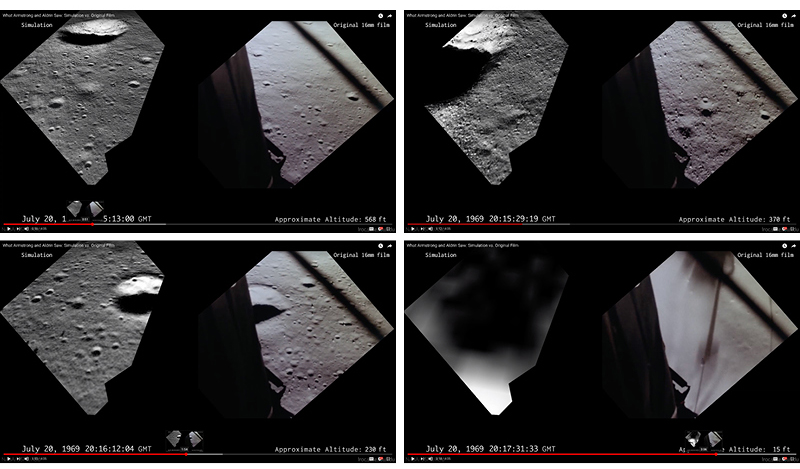

What Armstrong and Aldrin Saw: Simulation vs. Original 16mm Film

WANT CHILLS TO GO UP YOUR SPINE? WATCH AND LISTEN TO THIS! The only visual record of the historic Apollo 11 landing is from a 16mm time-lapse (6 frames per second) movie camera mounted in Buzz Aldrin’s window. The visual above is from the footage (l to r) at 568 feet, 370 feet, 230 feet and 15 feet. More notes and links on the You Tube page.