Nice Moves

top row l to r: Gary Kasparov in 1997 training for his May rematch with an upgraded Deep Blue; Time cover May 5, 1997 (cover price $2.95); Garry Kasparov retired from professional chess March 10, 2005. This photo is from 2007.

middle row l to r: Garry at age 11; Kasparov becomes World Junior Champion at Dortmund in 1980; Kasparov-after winning the FIDE World Championship title in 1985; Interesting quote referring to Deep Blue by Yasser Seirawan.

bottom row l to r: The 6′ 5″, 1.4 ton Deep Blue; Deep Blue’s processor board; The MacBook Pro’s processor board (you’ve come a long way, baby).

Hopefully most of you had a chance to watch the Superbowl last weekend. Wow! So much to take away (I could probably use the game and coaching highlights as my blog reference and write about it for months) – effort, perseverance, hard work, leadership, strategy, witty commercials, flying Gaga, surprises and NEVER QUITTING! Dozens and dozens of top athletes going head to head competing on the world stage.

For all of the history around this game, twenty years ago on this day, another champion was on the world stage, forever changing our perception of human and machine intelligence. On Feb 10th in Philadelphia, Garry Kosparov took on Deep Blue, a chess-playing computer developed by IBM, known for being the first computer chess-playing system to win a chess game against a reigning world champion under regular time controls. Fast forward to today, chess-playing computers, and super-advanced artificial intelligence (AI), are now accessible to the average consumer. There are many chess engines to choose from, such as Stockfish, Crafty, Fruit and GNU Chess that can be downloaded for free, able to play a game that, when run on an up-to-date personal computer or mobile phone, can defeat most master players under tournament conditions. For those who have played chess, and have the inclination to learn more, here’s some trivia I know you’ll enjoy (and thanks Wikipedia for the info!)

- Using “ends-and-means” heuristics, a human chess player can intuitively determine optimal outcomes and how to achieve them regardless of the number of moves necessary, but a computer must be systematic in its analysis.

- Most players agree that looking at least five moves ahead, called five plies, when necessary is required to play well. Normal tournament rules give each player an average of three minutes per move. On average there are more than 30 legal moves per chess position, so a computer must examine a quadrillion possibilities to look ahead ten plies (five full moves); one that could examine a million positions a second would require more than 30 years.

- After discovering refutation screening (the application of alpha-beta pruning to optimizing move evaluation), in 1957, a team at Carnegie Mellon University predicted that a computer would defeat the world human champion by 1967. The team did not anticipate the difficulty of determining the right order to evaluate branches. Researchers worked to improve programs’ ability to identify killer heuristics, unusually high-scoring moves to reexamine when evaluating other branches.

- Into the 1970s, most top chess players believed that computers would not soon be able to play at a Masters level. In 1968 International Master David Levy made a famous bet that no chess computer would be able to beat him within ten years. In 1976 Senior Master and professor of psychology Eliot Hearst of Indiana University wrote that “the only way a current computer program could ever win a single game against a master player would be for the master, “perhaps in a drunken stupor while playing 50 games simultaneously, to commit some once-in-a-year blunder”.

- In the late 1970s chess programs suddenly began defeating top human players. The year of Hearst’s statement, Northwestern University’s Chess 4.5 at the Paul Masson American Chess Championship’s Class B level became the first to win a human tournament. Levy won his bet in 1978 by beating Chess 4.7, but it achieved the first computer victory against a Master-class player at the tournament level by winning one of the six games. In 1980 Belle, the first computer designed for chess playing, began often defeating Masters.

- The sudden improvement without a theoretical breakthrough surprised humans, who did not expect that Belle’s ability to examine 100,000 positions a second—about eight plies—would be sufficient. The Spracklens, creators of the successful microcomputer program Sargon, estimated that 90% of the improvement came from faster evaluation speed and only 10% from improved evaluations. New Scientist stated in 1982 that computers “play terrible chess … clumsy, inefficient, diffuse, and just plain ugly”, but humans lost to them by making “horrible blunders, astonishing lapses, incomprehensible oversights, gross miscalculations, and the like” much more often than they realized.

- By the early ‘80’s microcomputer chess programs could evaluate up to 1,500 moves a second and were as strong as mainframe chess programs of five years earlier, able to defeat almost all players. While only able to look ahead one or two plies more than at their debut in the mid-1970s, doing so improved their play more than experts expected; seemingly minor improvements “appear to have allowed the crossing of a psychological threshold, after which a rich harvest of human error becomes accessible.” In 1984 BYTE magazine wrote that “Computers—mainframes, minis, and micros—tend to play ugly, inelegant chess”, but noted Robert Byrne’s statement that “tactically they are freer from error than the average human player”.

- At the 1982 North American Computer Chess Championship, Monroe Newborn predicted that a chess program could become world champion within five years; tournament director and International Master Michael Valvo predicted ten years; the Spracklens predicted 15; Ken Thompson predicted more than 20; and others predicted that it would never happen. The most widely held opinion, however, stated that it would occur around the year 2000.

- In 1989, Levy was defeated by Deep Thought in an exhibition match. Deep Thought, however, was still considerably below World Championship Level, as the then reigning world champion Garry Kasparov demonstrated in two strong wins in 1989.

- It was not until a 1996 match with IBM’s Deep Blue that Kasparov lost his first game to a computer at tournament time controls in Deep Blue – Kasparov, 1996, Game 1. For my “chess friendly” readers, the first match went as follows: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Y9hriLylIo

- This game was, in fact, the first time a reigning world champion had lost to a computer using regular time controls. However, Kasparov regrouped to win three and draw two of the remaining five games of the match, for a convincing victory.

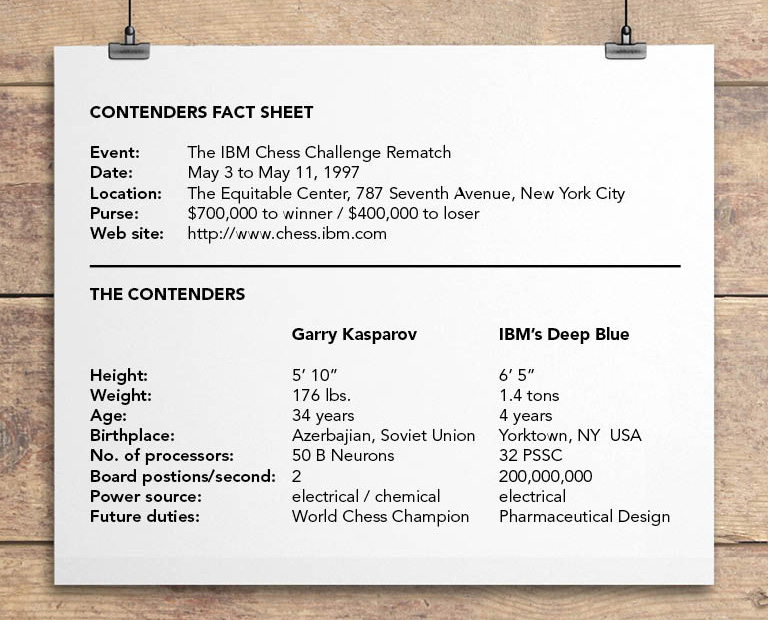

- In May 1997, an updated version of Deep Blue defeated Kasparov 3 1/2 – 2 1/2 in a return match. A documentary mainly about the confrontation was made in 2003, titled Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine. IBM keeps a web site of the event.

- The 1997 match took place not on a standard stage, but rather in a small television studio. The champion and computer met at the Equitable Center in New York, with cameras running, press in attendance and millions watching the outcome. The audience watched the match on television screens in a basement theater in the building, several floors below where the match was actually held. The theater seated about 500 people, and was sold out for each of the six games. The media attention given to Deep Blue resulted in more than three billion impressions around the world.

- The odds of Deep Blue winning were not certain, but the science was solid. The IBM team knew their machine could explore up to 200 million possible chess positions per second. The chess grandmaster won the first game, Deep Blue took the next one, and the two players drew the three following games. Game 6 ended the match with a crushing defeat of the champion by Deep Blue.

- The match’s outcome made headlines worldwide, and helped a broad audience better understand high-powered computing. Deep Blue had an impact on computing in many different industries. It was programmed to solve the complex, strategic game of chess, so it enabled researchers to explore and understand the limits of massively parallel processing. This research gave developers insight into ways they could design a computer to tackle complex problems in other fields, using deep knowledge to analyze a higher number of possible solutions.

- The architecture used in Deep Blue was applied to financial modeling, including marketplace trends and risk analysis; data mining—uncovering hidden relationships and patterns in large databases; and molecular dynamics, a valuable tool for helping to discover and develop new drugs.

- Ultimately, Deep Blue was retired to the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C.