Just Sign Here

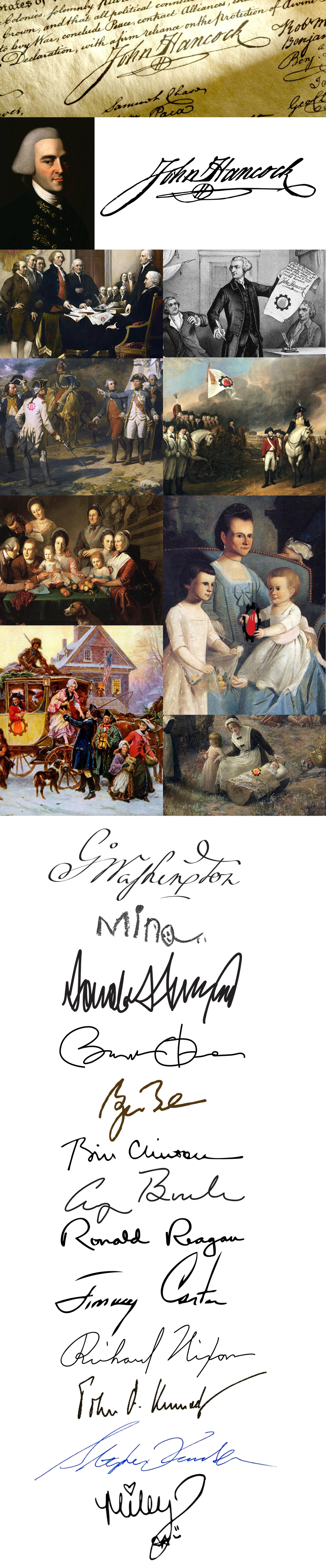

(top and row two) Maybe the most famous signature ever, John Hancock. That’s a painting of him next to a clean look at his wonderful sig; (row three) Debating the declaration of Independence and getting the signing process underway; (row four) depictions of the good guys getting ready to battle the British; (the rest of the images) Paintings depicting colonial life. I especially like the portrait on the right with the baby on mom’s lap playing with her favorite toy. (presidential signatures from top to bottom) Our very first president, George Washington. His signature on his personal copy of the Acts of Congress is currently worth $9.8 Million; Next is my friend’s granddaughter Mina’s signature. She will be eligible to run for president in 2050. She’s four. But she will be president. At this point her running platform rests on free ice cream and unlimited views of Frozen for all. That may evolve over time; Next is the current resident of the white house, President Donald Trump; Then Barack Obama; George W. Bush; Bill Clinton; George H. W. Bush; Ronald Reagan (nice sig); Jimmy Carter (another nice sig); Richard Nixon; John F. Kennedy; And the president of Kowalski Heat Treating Company, me; And that last one is Miley Cyrus’ sig. She’s not a president and isn’t planning to run as far as I know but Mina likes her and how she dots her “i” with a heart and tucks in that smiley face by the “y.”

Working at the desk early this morning, I was reviewing some letters that had to go out (yes, you remember, those typed pages of 8 ½ x 11 paper, with dates on the top, customer names, body text and a formal signature) – unlike the e communications we zip around day and night – and I took pause as I applied my signature Not sure why, but I thought back to when I was a wee tot reviewing my penmanship grades with my parents. Unfortunately, I always received the dreaded U-. Back then we all still were taught to write in cursive, the wonderful Nuns kept telling my parents that I was hopeless! If you were to ask Jackie or my girls, they simply will tell you I am “unique”! Our signatures are a real statement of approval, confirmation and credence to documents. Once you “sign” something it becomes permanent, meaningful and often a binding obligation (think credit card agreements). “If it is not in writing it doesn’t happen” – this adage is something I live by both professionally and personally – just ask my kids! I’ve always been a big fan of American history and the famous John Hancock signature (that dude had seriously good penmanship, as many did back then) on our Declaration. Turns out, today, August 2, is the official recognized day that the remaining signers of the Declaration completed the document (56 signatures) – it was only partially signed when it became official on July 4th. I jumped on the internet and dug up some cool info on how this amazing document came to be and the history about our brave declaration to the King of England. Enjoy, and thanks Wikipedia and history.com for the info and history lesson. I am continually amazed at what these folks created all those years ago!

- The United States Declaration of Independence is the statement adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on July 4, 1776. The Declaration announced that the Thirteen Colonies at war with the Kingdom of Great Britain would regard themselves as thirteen independent sovereign states, no longer under British rule. With the Declaration, these new states took a collective first step toward forming the United States of America.

- The colonies were not directly represented in Parliament, and colonists argued that Parliament had no right to levy taxes upon them. This tax dispute was part of a larger divergence between British and American interpretations of the British Constitution and the extent of Parliament’s authority in the colonies. The orthodox British view, dating from the Glorious Revolution of 1688, was that Parliament was the supreme authority throughout the empire, and so, by definition, anything that Parliament did was constitutional. In the colonies, however, the idea had developed that the British Constitution recognized certain fundamental rights that no government could violate, not even Parliament.

- The issue of Parliament’s authority in the colonies became a crisis after Parliament passed the Coercive Acts (known as the Intolerable Acts in the colonies) in 1774 to punish the colonists for the Gaspee Affair of 1772 and the Boston Tea Party of 1773. Many colonists saw the Coercive Acts as a violation of the British Constitution and thus a threat to the liberties of all of British America, so the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in September 1774 to coordinate a response. Congress organized a boycott of British goods and petitioned the king for repeal of the acts. These measures were unsuccessful because King George and the ministry of Prime Minister Lord North were determined to enforce parliamentary supremacy in America. As the king wrote to North in November 1774, “blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent”.

- Most colonists still hoped for reconciliation with Great Britain, even after fighting began in the American Revolutionary War at Lexington and Concord in April 1775. The Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in May 1775, and some delegates hoped for eventual independence, but no one yet advocated declaring it. Many colonists no longer believed that Parliament had any sovereignty over them, yet they still professed loyalty to King George, who they hoped would intercede on their behalf. They were disappointed in late 1775 when the king rejected Congress’s second petition, issued a Proclamation of Rebellion, and announced before Parliament on October 26 that he was considering “friendly offers of foreign assistance” to suppress the rebellion.

- Despite this growing popular support for independence, Congress lacked the clear authority to declare it. Delegates had been elected to Congress by 13 different governments, and they were bound by the instructions given to them. Regardless of their personal opinions, delegates could not vote to declare independence unless their instructions permitted such an action.

- While many of the colonies were split on independence, as was the custom, Congress appointed a committee to draft a preamble to explain the purpose of the resolution. John Adams wrote the preamble, which stated that because King George had rejected reconciliation and was hiring foreign mercenaries to use against the colonies, “it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed”. Adams’s preamble was meant to encourage the overthrow of the governments of Pennsylvania and Maryland, which were still under proprietary governance. Congress passed the preamble on May 15 after several days of debate, but four of the middle colonies voted against it, and the Maryland delegation walked out in protest.Adams regarded his May 15 preamble effectively as an American declaration of independence, although a formal declaration would still have to be made.

- On the same day that Congress passed Adams’s radical preamble, the Virginia Convention set the stage for a formal Congressional declaration of independence. On May 15, the Convention instructed Virginia’s congressional delegation “to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain”. In accordance with those instructions, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented a three-part resolution to Congress on June 7. The motion was seconded by John Adams, calling on Congress to declare independence, form foreign alliances, and prepare a plan of colonial confederation. The part of the resolution relating to declaring independence read:

Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved. - Total support for a Congressional declaration of independence was consolidated in the final weeks of June 1776. Connecticut, New Hampshire and Delaware authorized their delegates to declare independence. In Pennsylvania, political struggles ended with the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and a new Conference of Committees under Thomas McKean authorized Pennsylvania’s delegates to declare independence on June 18. The Provincial Congress of New Jersey had been governing the province since January 1776; they resolved on June 15 that Royal Governor William Franklin was “an enemy to the liberties of this country” and had him arrested. On June 21, they chose new delegates to Congress and empowered them to join in a declaration of independence.

- Only Maryland and New York had yet to authorize independence towards the end of June. Previously, Maryland’s delegates had walked out when the Continental Congress adopted Adams’s radical May 15 preamble, and had sent to the Annapolis Convention for instructions, rejecting Adams’s preamble, instructing its delegates to remain against independence. But Samuel Chase went to Maryland and, thanks to local resolutions in favor of independence, was able to get the Annapolis Convention to change its mind on June 28.

- Only the New York delegates were unable to get revised instructions. When Congress had been considering the resolution of independence on June 8, the New York Provincial Congress told the delegates to wait.But on June 30, the Provincial Congress evacuated New York as British forces approached, and would not convene again until July 10. This meant that New York’s delegates would not be authorized to declare independence until after Congress had made its decision.

- Political maneuvering was setting the stage for an official declaration of independence even while a document was being written to explain the decision. On June 11, 1776, Congress appointed a “Committee of Five” to draft a declaration, consisting of John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. The committee took no minutes, so there is some uncertainty about how the drafting process proceeded. What is certain is that the committee discussed the general outline which the document should follow and decided that Jefferson would write the first draft.

- Congress ordered that the draft “lie on the table”and then methodically edited Jefferson’s primary document for the next two days, shortening it by a fourth, removing unnecessary wording, and improving sentence structure. They removed Jefferson’s assertion that Great Britain had forced slavery on the colonies in order to moderate the document and appease persons in Great Britain who supported the Revolution. Jefferson wrote that Congress had “mangled” his draft version, but the Declaration that was finally produced was “the majestic document that inspired both contemporaries and posterity,” in the words of his biographer John Ferling.

- A vote was taken after a long day of speeches, each colony casting a single vote, as always. The delegation for each colony numbered from two to seven members, and each delegation voted amongst themselves to determine the colony’s vote. Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against declaring independence. The New York delegation abstained, lacking permission to vote for independence. Delaware cast no vote because the delegation was split between Thomas McKean, who voted yes, and George Read, who voted no. The remaining nine delegations voted in favor of independence, which meant that the resolution had been approved by the committee of the whole. The next step was for the resolution to be voted upon by Congress itself. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina was opposed to Lee’s resolution but desirous of unanimity, and he moved that the vote be postponed until the following day.

- On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained, allowing the delegation to vote three-to-two in favor of independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the timely arrival of Caesar Rodney, who voted for independence. The New York delegation abstained once again since they were still not authorized to vote for independence, although they were allowed to do so a week later by the New York Provincial Congress.

- The resolution of independence was adopted with twelve affirmative votes and one abstention, and the colonies officially severed political ties with Great Britain. John Adams wrote to his wife on the following day, writing:

I am apt to believe that [Independence Day] will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more. - The Declaration was transposed on paper and signed by John Hancock, President of the Congress, on July 4, 1776, according to the 1911 record of events by the U.S. State Department. About thirty-four delegates signed the Declaration on July 4, and the others signed on or after August 2.Some historians maintain that most delegates signed on August 2, and that those eventual signers who were not present added their names at a later date.

EXTRAS…

Video of a talented guy making John Hancock’s calligraphy signature

All the President’s Pens: Video of White House Staff Secretary Lisa Brown explains why presidents use so many pens to sign legislation.

An historical event: President Kennedy Signs Test Ban Treaty (1963)