Brilliant

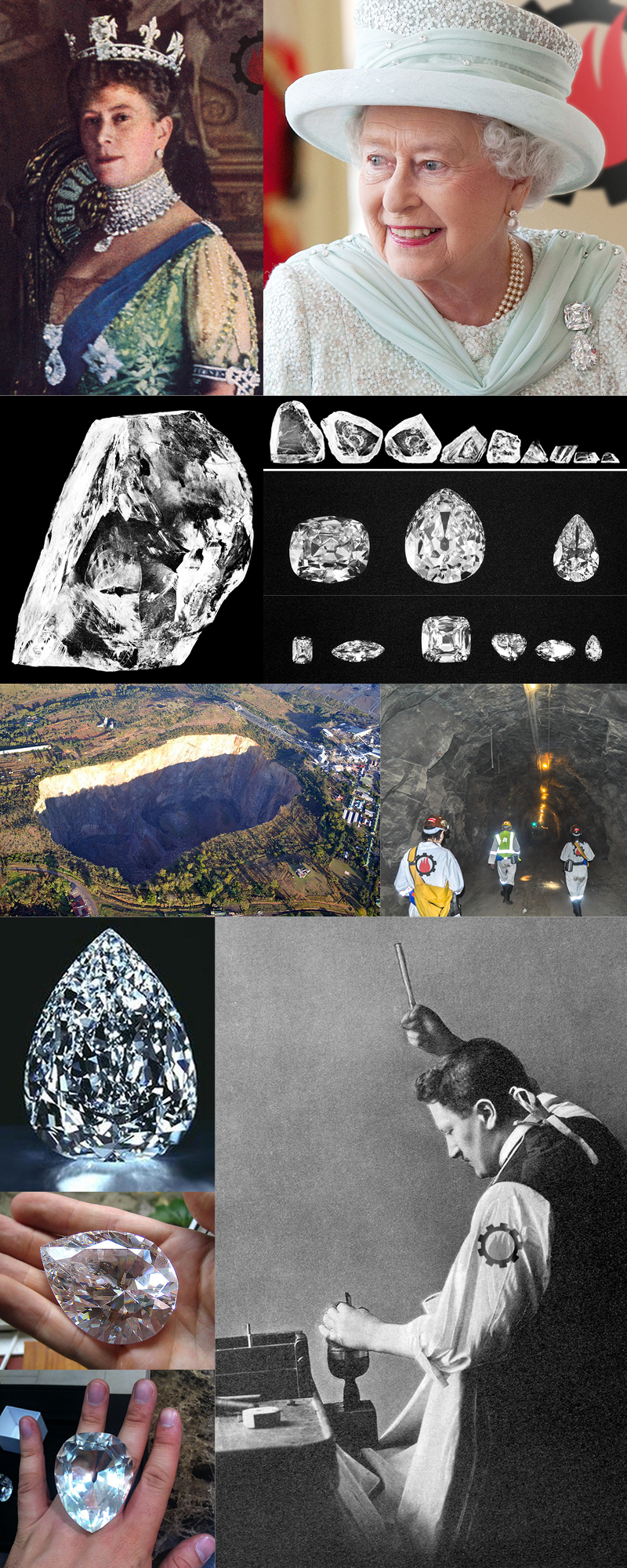

(top, l to r) 1914 ,Queen Mary wearing Cullinans I and II as a brooch on her chest, III as a pendant on the Coronation Necklace, and IV in the base of her crown, below the Koh-i-Noor; Queen Elizabeth II wearing the same Cullinan diamonds brooch more than 100 years later. (row 2 left) The raw diamond (row 2 right top) The nine rough cut diamonds (row 2 right bottom) The nine Cullinans in all their glory. (row 3) The Cullinan Mine in South Africa; Inside the mine. (bottom left) The Cullinan I, or the Great Star of Africa, 530.2 carats of beauty and fun for some lucky enough to touch it. (bottom right) Joseph Asscher ready to take the first whack at splitting the Cullinan diamond. No pressure there.

This past weekend, I had the pleasure, along with my neighbors, of shoveling and snow blowing after our first major storm of the year hit us hard. As a native northeast Ohioan, I was ok with lacing up my boots, throwing on the hat and gloves, and tackling the task. The little kid in me still enjoys firing up the snow blower and slowly blasting it up in the air and out across the lawn. Of course, with the wind, and driving snow, I had to revisit the driveway and do it all over again on Sunday. During my time in the cold, the sun came out, and the snow turned to an amazing layer of sparkles and light, shimmering in front of me as I worked along, like a field of diamonds. Once I finished, I came inside, warmed back up, and started poking around on the computer, looking for cool and fun facts for this week’s blog. I discovered the Cullinan, and a great article on Wikipedia about the world’s largest diamond ever found. Turns out, it celebrates its 114th year birthday this weekend. And, sorry Jackie, I inquired, but looks like the Queen’s not gonna give ‘em up soon. Enjoy!

The Cullinan Diamond is the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found, weighing 3,106.75 carats (621.35 g), discovered at the Premier No. 2 mine in Cullinan, South Africa, on 26 January 1905.

It was found 18 feet below the surface at Premier Mine in Cullinan, Transvaal Colony, by Frederick Wells, surface manager at the mine. It was approximately 10.1 centimetres (4.0 in) long, 6.35 centimetres (2.50 in) wide, 5.9 centimetres (2.3 in) deep.

Four of its eight surfaces were smooth, indicating that it once had been part of a much larger stone broken up by natural forces. (wonder just how big that was) It had a blue-white hue and contained a small pocket of air, which at certain angles produced a rainbow, or Newton’s rings, a phenomenon in which an interference pattern is created by the reflection of light between two surfaces—a spherical surface and an adjacent touching flat surface.

Newspapers called it the “Cullinan Diamond”, a reference to Sir Thomas Cullinan, who opened the mine in 1902. It was three times the size of the previous largest Excelsior Diamond, found in 1893 at Jagersfontein Mine, weighing 972 carats. Shortly after its discovery, Cullinan went on public display at the Standard Bank in Johannesburg, where it was seen by an estimated 8,000–9,000 visitors.

In April 1905, the rough gem was deposited with Premier Mining Co.’s London sales agent, S. Neumann & Co. Due to its immense value, detectives were assigned to a steamboat that was rumored to be carrying the stone. A parcel was ceremoniously locked in the captain’s safe and guarded on the entire journey. It was a diversionary tactic – the stone on that ship was fake, meant to attract those who would be interested in stealing it. Cullinan was sent to the United Kingdom in a plain box via registered post.

On arriving in London, it was conveyed to Buckingham Palace for inspection by King Edward VII. It drew considerable interest from potential buyers, but Cullinan went unsold for two years. In 1907 the Transvaal Colony government bought the Cullinan to formally present to the king.

Initially, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, then British Prime Minister, advised the king to decline the offer, but he later decided to let Edward VII choose whether or not to accept the gift. Eventually, he was persuaded by Winston Churchill, then Colonial Under-Secretary. (For his trouble, Churchill was sent a replica of the diamond, which he enjoyed showing off to guests on a silver plate). The Transvaal Colony government bought the diamond on for £150,000 or about US$750,000 at the time, which adjusted for pound-sterling inflation is equivalent to about £20 million today. Unnoticed, due to a 60% tax imposed on mining profits at the time, the Treasury received most of its money back from the Premier Diamond Mining Company.

The diamond was presented to the king at Sandringham House on November 9, 1907 – his sixty-sixth birthday – in the presence of a large party of guests, including the Queen of Norway, the Queen of Spain, the Duke of Westminster and Lord Revelstoke. The king asked his colonial secretary, Lord Elgin, to announce that he accepted the gift “for myself and my successors” and that he would ensure “this great and unique diamond be kept and preserved among the historic jewels which form the heirlooms of the Crown”.

The king chose Asscher Brothers of Amsterdam to cleave and polish the rough stone into brilliant gems of various cuts and sizes. (talk about your PIA (Pain in the @%$) Jobs! Abraham Asscher collected it from the Colonial Office in London in January 1908. He returned to the Netherlands by train and ferry with the diamond in his coat pocket. Meanwhile, to much fanfare, a Royal Navy ship carried an empty box across the North Sea, again throwing off potential thieves. Even the captain had no idea that his “precious” cargo was a decoy.

On 10 February 1908, the rough stone was split in half by Joseph Asscher at his diamond-cutting factory in Amsterdam. At the time, technology had not yet evolved to guarantee the quality of modern standards, and cutting the diamond was difficult and risky. After weeks of planning, an incision 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) deep was made to enable Asscher to cleave the diamond in one blow. Making the incision alone took four days, and a steel knife broke on the first attempt, but a second knife was fitted into the groove and split it clean in two along one of four possible cleavage planes. In all, splitting and cutting the diamond took eight months, with three people working 14 hours per day to complete the task.

“The tale is told of Joseph Asscher, the greatest cleaver of the day,” wrote Matthew Hart in his book Diamond: A Journey to the Heart of anObsession (2002), “that when he prepared to cleave the largest diamond ever known … he had a doctor and nurse standing by and when he finally struck the diamond … he fainted dead away”. Lord Ian Balfour, in his book Famous Diamonds (2009), dispels the fainting story, suggesting it was more likely Joseph would have celebrated, opening a bottle of champagne.

Cullinan produced 9 major stones of 1,055.89 carats (211.178 g) in total, and 96 minor brilliants weighing 7.55 carats (1.510 g) (on average, 0.079 carats each) – a yield from the rough stone of 34.25 per cent. There are also 9.5 carats (1.90 g) of unpolished fragments.

- Cullinan I, or the Great Star of Africa, is a pendeloque-cut brilliant weighing 530.2 carats (106.04 g) and has 74 facets. It is set at the top of the Sovereign’s Scepter with Cross which had to be redesigned in 1910 to accommodate it.

- Cullinan II, or the Second Star of Africa, is a cushion-cut brilliant with 66 facets weighing 317.4 carats (63.48 g) set in the front of the Imperial State Crown, below the Black Prince’s Ruby (a large spinel).

- Cullinan III, or the Lesser Star of Africa, is pear-cut and weighs 94.4 carats (18.88 g). In 1911, Queen Mary, wife and queen consort of George V, had it set in the top cross pattée of a crown that she personally bought for her coronation.

- Cullinan IV, also referred to as a Lesser Star of Africa, is square-cut and weighs 63.6 carats (12.72 g). On 25 March 1958, while she and Prince Philip were on a state visit to the Netherlands, the Queen Elizabeth II revealed that Cullinan III and IV are known in her family as “Granny’s Chips”. They visited the Asscher Diamond Company, where Cullinan had been cut 50 years earlier. During her visit, she unpinned the brooch and offered it for examination to Louis Asscher, nephew of Joseph Asscher, who split the rough diamond. Aged 84, he was deeply moved by the fact the Queen had brought the diamonds with her, knowing how much it would mean to him seeing them again after so many years.

- Cullinan V is an 18.8-carat (3.76 g) heart-shaped diamond set in the center of a platinum brooch that formed a part of the stomacher made for Queen Mary to wear at the Delhi Durbar in 1911. The brooch was designed to show off Cullinan V and is pavé-set with a border of smaller diamonds. It can be suspended from the VIII brooch and can be used to suspend the VII pendant.

- Cullinan VI is marquise-cut and weighs 11.5 carats (2.30 g). It hangs from the brooch containing Cullinan VIII and forming part of the stomacher of the Delhi Durbar parure. Cullinan VI along with VIII can also be fitted together to make yet another brooch, surrounded by some 96 smaller diamonds. The design was created around the same time that the Cullinan V heart-shaped brooch was designed, both having a similar shape.

- Cullinan VII is also marquise-cut and weighs 8.8 carats (1.76 g). It was originally given by Edward VII to his wife and consort Queen Alexandra. After his death she gave the jewel to Queen Mary, who had it set as a pendant hanging from the diamond-and-emerald Delhi Durbar necklace, part of the parure.

- Cullinan VIII is an oblong-cut diamond weighing 6.8 carats (1.36 g). It is set in the center of a brooch forming part of the stomacher of the Delhi Durbar parure. Together with Cullinan VI it forms a brooch.

- Cullinan IX is smallest of the principal diamonds to be obtained from the rough Cullinan. It is a pendeloque or stepped pear-cut stone, weighs 4.39 carats (0.878 g), and is set in a platinum ring known as the Cullinan IX Ring.