OUCH!

Yikes!!!!!

See how needles are made HERE.

See how a machine pre-fills syringes HERE.

And see some historical collectables at the bottom.

What’s the most common question these days? …. Yep, “did you get your shot(s) yet.” Seems like it opens just about every conversation. As you know, the government, retailers and industry are racing to distribute the vaccine as quickly as possible. Depending on your age, and health status, you may already have received your shot(s). I know “getting a shot” is not always the most enjoyable event, but it’s just part of medicine distribution these days. Here’s some history on the syringe and needles (thanks again to the Greeks and Romans for their genius). Enjoy. Thanks to University of Queensland and omnisurge.co.za for the cool info.

How I learned to get a shot (how cool is this doc?)

Syringes are pretty basic, standard items that are used daily in the medical industry. Their design is fairly simple and straightforward, and completely effective for their purpose. It’s not a medical tool we think about too much, it’s there, it gets used, and it’s disposed of. But did you know that this commonplace device has a rich and varied history dating back thousands of years? It had quite the journey to get to where it is today.

A syringe is a simple pump consisting of a plunger that fits tightly into a cylindrical tube. The plunger can be pulled and pushed along inside the tube, allowing the syringe to pull in or push out a liquid or gas through the opening at the end of the tube. That open end may also be fitted with a hypodermic needle, a nozzle, or tubing to help direct the flow into and out of the tube.

The word “syringe” is derived from the Greek word syrinx, meaning “tube”.

The first syringes were used in Roman times during the 1st century AD. They are mentioned in a journal called De Medicina as being used to treat medical complications. Then, in the 9th century AD, an Egyptian surgeon created a syringe using a hollow glass tube and suction.

In 1650 Blaise Pascal invented a syringe as an application of fluid mechanics that is now called Pascal’s law. He used it in testing his theory that pressure exerted anywhere in a confined fluid is transmitted equally in all directions and that the pressure variations remain the same.

An Irish physician named Francis Rynd invented the hollow needle and used it to make the first recorded subcutaneous injections in 1844. Then shortly thereafter in 1853 Charles Pravaz and Alexander Wood developed a medical hypodermic syringe with a needle fine enough to pierce the skin. Alexander Wood experimented with injected morphine to treat nerve conditions. He and his wife subsequently became addicted to morphine and his wife is recorded as the first woman to die of an injected drug overdose.

In 1899 Letitia Mumford Geer of New York was granted a patent for a syringe design that permitted the user to operate it one-handed.

However, things got more interesting and advanced in 1946 when Chance Brothers in England produced the first all-glass syringe with an interchangeable barrel and plunger. This was revolutionary because it allowed the mass-sterilization of the different components without needing to match up the individual parts.

Shortly thereafter Australian inventor Charles Rothauser created the world’s first plastic, disposable hypodermic syringe made from polyethylene at his Adelaide factory in 1949. However, because polyethylene softens with heat, the syringes had to be chemically sterilized prior to packaging, which made them expensive. Two years later he produced the first injection-molded syringes made of polypropylene, a plastic that can be heat-sterilized. Millions were made for Australian and export markets.

Then in 1956 a New Zealand pharmacist and inventor Colin Murdoch was granted patents for a disposable plastic syringe. It was closely followed by the Plastipak – a plastic disposable syringe introduced by Becton Dickinson in 1961. In 1974 African American inventor Phil Brooks received a US patent for a “Disposable Syringe”.

These days syringes are used, not only in the medical and health industry, but in various other areas too. They can be used in certain forms of cooking to inject liquids into certain foods. They are also commonly used to refill ink cartridges for printers, inject glue or lubricants into hard-to-reach places, for precision measurement when mixing liquids, and even to feed small animals when they are being hand-reared.

Indeed, there are few medical tools so commonplace, and yet so indispensable, as the plastic disposable syringe and replacement needles.

Looking to the future of the parenteral administration of medicines and vaccines, it’s likely that there will be increasing use of direct percutaneous absorption, especially for children. Micro-silicon-based needles, so small that they don’t trigger pain nerves are being developed, however, these systems cannot deliver intravenous or bolus injections so hypodermic needles, with or without syringes, are likely to be with us for a long time. They are also required for catheter-introduced surgical procedures in deep anatomical locations.

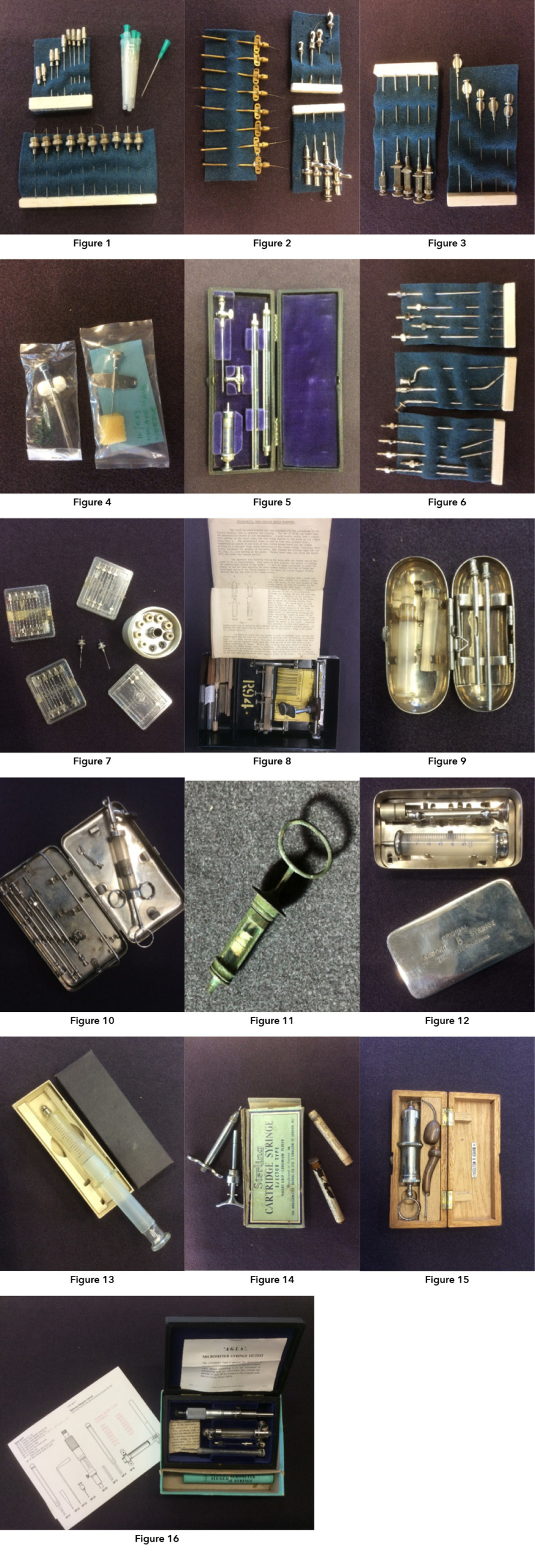

Some needles from the collection:

- Figure 1 shows three generations of needles. The top left ones are single-use needles from the 1950s with various lengths and gauges. At the top right is small sample of needles of a currently used type, supplied in a patent wrapper in their individual protective sheathes, with colour coded plastic hubs. Below these are the 1930s screw-on double ended needles patented by Boots & Co Ltd to fit their cartridge loading syringes. The internal point pierced the rubber bung on pre-dosed cartridges which could be inserted in the patent syringe.

- The range of needles is extensive. Each manufacturer produced a different shaped hub. Also, the taper of the nozzle was non-standard though most used were the ‘Luer’ and then the more tapered ‘Record’ but in addition to this were different locking devices to fit different syringe nozzles. The gauge and length of needles varies greatly according to their purpose. Figure 2 illustrates infusion needles in which the bulbous hub fits directly on to rubber tubing. Pneumothorax needles are for withdrawing air from the pleural cavity. The side arm allows for the attachment of a suction bottle using a two-way tap. The Hamilton Bailey type infusion canulae needles are eight from the early 20th century, made of gold for sterility, with slots through which to thread a support tape.

- Figure 4. Shows aspiration needles. They have a bevel-pointed introducer to facilitate insertion of the needle.

- Figure 4 below, shows two unused, ‘Gord’ type, infusion needles. Both are fitted with detachable rubber diaphragms to make repeated intravenous injection easier. With several minor variations they were used for many years until the 1960s when single use ‘Butterfly Needles’ were introduced.

- Figure 5: This is a 1930s portable lumbar puncture set used to measure the pressure of and test the cerebrospinal fluid which flows when the spinal meninges have been punctured.

- Figure 6: Haemorrhoid needles are characterised by a shoulder on the haft a few millimetres short of the needle tip to prevent deep penetration when injecting the haemorrhoids. A secure needle-lock ensured that the increased pressure required to inject the viscous oil did not detach the needle.

- The needles pictured below represent the range of needles and packaging which were commonplace between 1920 and 1950. They often became blunt with multiple use, were impossible to clean and sterilise adequately and caused infections leading to cellulitis and abscesses. Sharpening needles was sometimes solved by including a suitably shaped carborundum stone in the injection set. Needle sharpening devices were needed for rapid and consistent sharpening of many needles by large institutions (Figures 7. & 8.).

Syringes and Injection Sets:

- The Mussel Shell (Figure 9.), a pocket-sized syringe set, was patented by Burroughs Welcome, about 1910, particularly for use with tabloids, containing a standardised dose of soluble preparations to be injected after dissolving in distilled water. It was not until later that pharmaceutical manufacturers prepared sterile injections in sealed glass ampoules. Probably the oldest syringe in the collection (c1875) has a small metal barrel with a plain glass tube to contain a medication. It is crude and has a waxed linen piston with thumb-hold on the plunger. The needle has a screw fitting like another of the older syringes in the collection with its ferrous metal ends and non-sterilisable, ivory thumb piece on a plunger with a rubber piston. (Figure 11.)

- There were a variety in syringes made from all glass to all metal, but the Rekordspritze introduced by the Berlin instrument makers Dewitt and Hertz in 1906 gained prominence through its dependability, lack of leakage and jamming, and ease of dismantling to enable sterilisation. This pattern persisted until plastic superseded it. It was manufactured by many companies with minor modification all over the world. All glass syringes retained some popularity but were more susceptible to jamming and leaking (Figure 13.). Cartridge syringes were popular with dentists, and for emergency kits (Figure 14.).

- The collection contains several special purpose syringes and syringe sets. The anaesthetic syringe set was in common use by GPs and specialists. (Figure 10.). One that took us a while to identify is shown in Figure 15. The copper cased cannulas and the thick metal syringe with a robust screw lock retain heat to enable the injection of melted paraffin wax into hollow organs and vessels for demonstration specimens for morbid anatomy classes. Another unusual syringe is the AGLA Micrometre Syringe Outfit shown in Figure 16.This was designed for analysis of diluted concentrations of biological fluid components where accurate measurement of precise quantities is required. The enclosed booklet suggests that it was particularly used in immunology research and assessment where serial dilutions are critical, but toxicology would suggest itself as another application.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

DO YOU LIKE CONTESTS?

Me, too.

As you may know the Kowalski Heat Treating logo finds its way

into the visuals of my Friday posts.

I. Love. My. Logo.

One week there could be three logos.

The next week there could be 15 logos.

And sometimes the logo is very small or just a partial logo showing.

But there are always logos in some of the pictures.

So, I challenge you, my beloved readers, to count them and send me a

quick email with the total number of logos in the Friday post.

On the following Tuesday I’ll pick a winner from the correct answers

and send that lucky person some great KHT swag.

So, start counting and good luck!

Oh, and the logos at the very top header don’t count.

Got it? Good. :-))))

Have fun!!

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::