Hickory Dickory

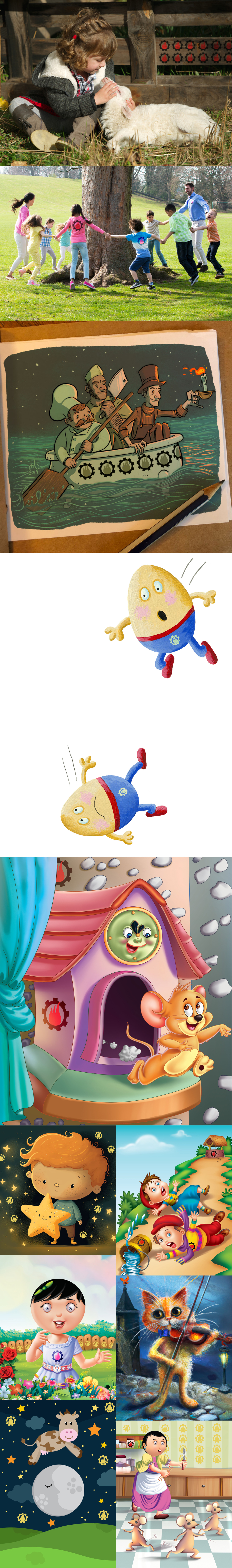

Rhymes twist the tongue and tickle mind. Besides the rhymes in this blog, there are six more illustrated above. Can you name them all? Let me know in an email. :))))

OK, I’ll admit it – I love being a Grandpa. There’s just something about the little ones that make me smile and laugh out loud. Seems, no matter how challenging my day is, or how many things are still on my “to do” list, I revel in the priority we make to “go see the grandkids”. Playing silly made-up games, (my favorite is when they hand you a broken toy, and say “here, you be this guy”), or having them ask me to chase them around the house! Climbing around on the floor with them, listening to them play by themselves, or just being together is a treat. Recently I found myself reading some nursery rhymes – you know , those silly rhyming poems that don’t seem to make much sense. So, of course, I did some digging, and found some great history/trivia to share. Much thanks to Wikipedia, Britannica.com, mentalfloss.comand interestingfacts.com for the insights. Now you know. Enjoy!

A nursery rhyme is a verse customarily told or sung to small children. The oral tradition of nursery rhymes is ancient, but new verses have steadily entered the culture. Most nursery rhymes date from the 16th, 17th, and, most frequently, the 18th centuries, but some are much older.

A French poem numbering the days of the month, similar to “Thirty days hath September,” was recorded in the 13th century; but such latecomers as “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” (by Ann and Jane Taylor; pub. 1806) and “Mary Had a Little Lamb” (by Sarah Josepha Hale; pub. 1830) seem to be just as firmly established.

The earliest known published collection of nursery rhymes was Tommy Thumb’s (Pretty) Song Book, 2 vol. (London, 1744). It included “Little Tom Tucker,” “Sing a Song of Sixpence,” and “Who Killed Cock Robin?” The most influential was Mother Goose’s Melody: or Sonnets for the Cradle, published by the firm of John Newbery in 1781. Among its 51 rhymes were “Jack and Jill,” “Ding Dong Bell,” and “Hush-a-bye baby on the tree top.”

Nursery rhymes have left a strong mark on many of our childhoods, but we often don’t realize where they came from. Some have evolved over centuries, bringing a whole new version to modern children, while others have remained tried and true since their inception. Here’s a couple favorites:

“Mary Had A Little Lamb”

Mary had a little lamb

Little lamb, little lamb

Mary had a little lamb

Its fleece was white as snow.

Poet Sarah Josepha Hale first published a version of this poem in 1830. Around 50 years later, an elderly woman named Mary Sawyer stepped forward as the real Mary. Sawyer’s story goes pretty much like the version we know and love today. She did take one to school. In a letter included in a 1928 book detailing the story, Sawyer says that the lamb grew up and had a few lambs of its own.

“Ring Around the Rosie”

Ring around the rosie

A pocket full of posies

Ashes, ashes

We all fall down.

You may have heard the popular Black Plague origin story for this rhyme, with the titular “ring” representing the red rings that would appear on the skin of people with the disease. However, there are other variations of the rhyme, such as 1883’s “Ring a ring a rosie/A bottle full of posie/All the girls in our town/Ring for little Josie,” that present different theories.

When he analyzed this version, folklorist Philip Hiscock offered a less deadly translation. Religious bans on dancing in Britain and North America in the 19th century led to “play parties,” with ring games that were similar to square dancing but without music, so the events quietly flew under the radar. “The rings referred to in the rhymes are literally the rings formed by the playing children,” explains Hiscock. “‘Ashes, ashes’ probably comes from something like ‘Husha, husha,’ another common variant which refers to stopping the ring and falling silent. And the falling down refers to the jumble of bodies in that ring when they let go of each other and throw themselves into the circle.”

“Rub a Dub Dub”

Rub-a-dub-dub,

Three men in a tub,

And who do you think they be?

The butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker,

And all of them out to sea.

Most American children know a heavily revised version of this rhyme with only men in a tub. But you need the original version to understand the origins of this 14th-century phrase: Hey, rub-a-dub – Ho, rub-a-dub – Three maids in a tub – And who do you think were there? – The butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker – And all of them going to the fair. According to author Chris Roberts, the “tub” here refers to a bawdy fairground attraction. “Today it would be perhaps a seedy venue,” Roberts said in 2005. “The upper-class, the respectable tradesfolk — the candlestick maker and the butcher and the baker — are ogling, getting an eyeful of some young ladies in a tub.” Mercy!

“Humpty Dumpty”

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

There’s nothing that makes Humpty an egg in this rhyme! That image was popularized by Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass in 1871, decades after the rhyme’s inception. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “humpty dumpty” had a few meanings before the wall came into it, including a drink with brandy and a short, dumpy, clumsy person. An 1881 book even features images of Humpty as a clown. A popular theory is that “humpty dumpty” refers to a cannon used during the Siege of Colchester in 1648. The idea that this rhyme is some kind of wartime ballad is pretty common. Before the cannon theory got traction, many believed the rhyme was about the usurpation of Richard III in 1483. However, according to the Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, the root of this nursery rhyme could be more innocent. While it’s unclear whether this game predates the rhyme, Humpty Dumpty was a popular game in the 19th century where girls would tuck their legs into their skirts, fall back, and then try to regain balance without letting go of their skirts. “Eggs do not sit on walls,” authors Peter and Iona Opie write. “But the verse becomes intelligible if it describes human beings who are impersonating eggs.”

“Hickory Dickory Dock”

Hickory dickory dock

The mouse went up the clock

The clock struck one

The mouse went down

Hickory dickory dock.

Some believe this counting rhyme was inspired by the astronomical clock at Exeter Cathedral in Devon, England, which was plagued by mice. Around 1600, the presiding bishop directed carpenters to cut a hole in the door to the clock room — or, as the records said at the time, “Paid ye carpenters 8d for cutting ye hole in ye north transept door for ye Bishop’s cat.” The cathedral’s cats got easy access to prey, cutting down the vermin population. Centuries later, the door is still there. But there’s a reason mice were so common around the clockwork: Animal fat was often used to lubricate clock parts during that time. It’s possible it was just written about a pretty normal thing to be happening on a clock at the time, but that’s not as fun.

To learn more, CLICK HERE

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

DO YOU LIKE CONTESTS?

Me, too.

As you may know the Kowalski Heat Treating logo finds its way

into the visuals of my Friday posts.

I. Love. My. Logo.

One week there could be three logos.

The next week there could be 15 logos.

And sometimes the logo is very small or just a partial logo showing.

But there are always logos in some of the pictures.

So, I challenge you, my beloved readers, to count them and send me a

quick email with the total number of logos in the Friday post.

On the following Tuesday I’ll pick a winner from the correct answers

and send that lucky person some great KHT swag.

So, start counting and good luck!

Oh, and the logos at the very top header don’t count.

Got it? Good. :-))))

Have fun!!

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::