Understanding El Niño

With all the talk this weekend of big snowstorms in the East, the mercury dropping and our love of everything thermal, I thought it would be fun to share the history and science behind an El Nino. Bundle up!

.

Simple, clear explanation:

Click to see VIDEO HERE

Geeky, nerdy, complex explanation:

El Niño – is so termed because it generally reaches full strength toward the end of the year, and early Christian inhabitants of western equatorial South America equated the warm water current and the resulting impacts with their holiday celebrating the birth of Jesus (known as El Niño in Spanish).

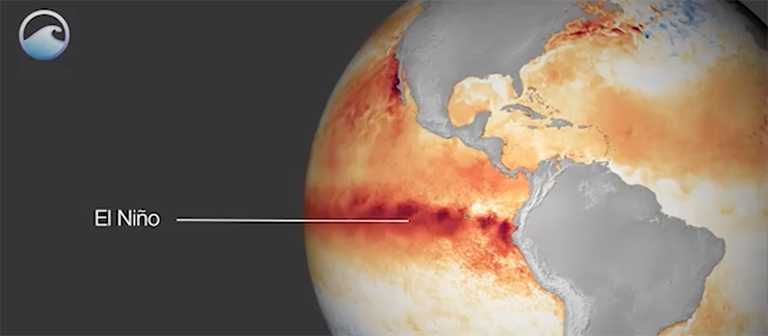

El Niño and the Humboldt Current – in normal, non-El Niño conditions, trade winds blow in a westerly direction along the equator, piling up warm surface water in the western Pacific, causing the sea surface to be as much as 18 inches higher than the east. These trade winds are one of the main sources of fuel for the Humboldt Current – a cold ocean current that flows north along the coasts of Chile and Peru, then turns west and warms as it moves out into the Central Pacific. So, the normal situation is warmer water in the western Pacific, cooler in the eastern.

In an El Niño, the equatorial westerly winds diminish, and as a result, the Humboldt Current weakens. This allows the waters along the coast of Chile and Peru to warm and creates warmer than usual conditions along the coast of South America. As far as we know, other forces, such as volcanic eruptions and sunspots, do not cause El Niños.

ENSO – El Niño and this Southern Oscillation (known as ENSO) is a periodic fluctuation in sea surface temperature (El Niño) and the air pressure of the overlying atmosphere (Southern Oscillation). This bimodal variation in sea level barometric pressure is measured between observation stations at Darwin, Australia and Tahiti and quantified in the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), a standardized difference between the two barometric pressures. Normally, lower pressure over Darwin and higher pressure over Tahiti encourages a circulation of air from east to west, drawing warm surface water westward and bringing precipitation to Australia and the western Pacific. When the pressure difference weakens, which is strongly coincidental with El Niño conditions, parts of the western Pacific, such as Australia experience severe drought, while across the ocean, heavy precipitation can bring flooding to the west coast of equatorial South America and changes to the north American continent.

Causes – The exact initiating causes of an ENSO warm or cool event are not fully understood. The strengthening and weakening of the trade winds is a function of changes in the pressure gradient of the atmosphere over the tropical Pacific. Ironically, the warming of the sea surface works to decrease the atmospheric pressure above it by transferring more heat to the atmosphere and making it more buoyant.

Infrared Radiation Effect – The connection between the Southern Oscillation and precipitation is also manifest in the quantity of long–wave (e.g., infrared) radiation leaving the atmosphere. Under clear skies, a great deal of the long–wave radiation released into the atmosphere from the surface can escape into space. Under cloudy skies, some of this radiation is prevented from escaping. Satellites are able to measure the amount of long–wave radiation reaching space, and from these observations, the relative amount of convection in different parts of the basin can be estimated.

For more detailed and more technical explanations, visit our article source at NOAA National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration – https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!