Up, Up and Away

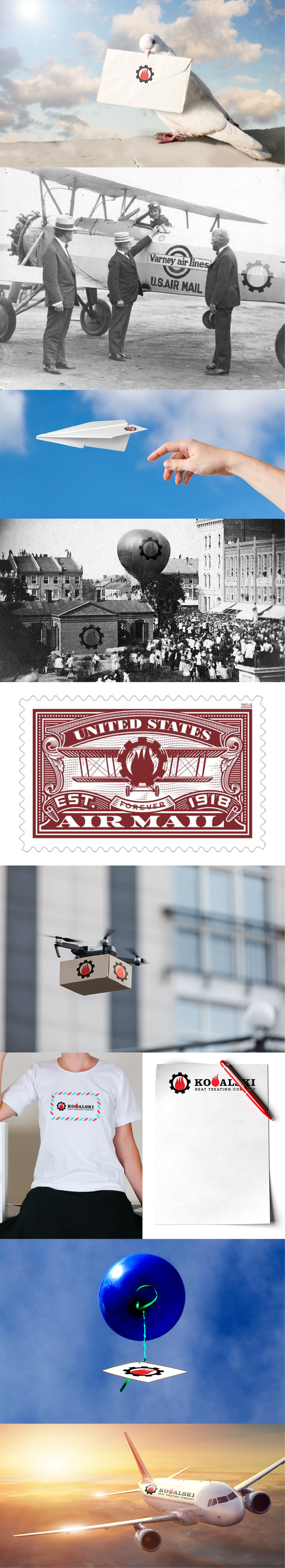

Airmail is a whole lot different since its humble balloon beginnings in 1859. (Fourth image down.)

>> And here’s something to LISTEN TO while you’re reading this fascinating post. :))))

We have some amazing technology today at our fingertips. I just finished an email to one of my very special customers, providing not only well wishes, but a quote and production schedule on his important PIA (Pain in the @%$) Job! What ease to type, insert info, instantly format, and then ”send” knowing within seconds the “letter” would safely and simply arrive on her desk. Guess we can call it our version of “air mail” today. Not so many years ago here in the good old US of A. airmail made its official debut. Hard to image, but next week on August 17th marks the 161st anniversary of the very first air mail flight over land, when a hot air balloon carried a package of 123 letters into the air destined to arrive in NY City. It launched what became known as the US Post Office “air mail” service, through some amazing efforts by the military, townspeople and really, really brave pilots. It also become the framework for local airports, lighted runways and early navigation systems. Here’s some fun history about the first official flight, and subsequent milestones in mail delivery aviation. Hats off to all of my aerospace customers – you continue the make it possible to fly. Special thanks to Wired Magazine and the USPO for the info. Enjoy!

- On a hot summer day on August 17th 1859, the temperature soared toward 91 degrees, John Wise stood at the town square in Lafayette, Indiana, standing next to a balloon named Jupiter. Even for a balloon enthusiast and a well-known aeronaut, it was a big moment. Wise was set to carry what would be the first U.S. airmail. A postmaster had handed him a bag with 123 letters. Destination of the balloonist and his precious cargo: New York City.

- Delivering letters by air had been attempted before and there had always been carrier pigeons. And in 1785, a balloon flight from Dover, England, to Calais, France, had carried mail. Wise’s attempt was to be the big event for the United States. Wise, who was 51, was also hoping to set a record for the longest balloon flight. He took off at 2 p.m.

- But the weather wasn’t on his side. He found that the wind was blowing southwest, not east. Still, he went up to 14,000 feet. But five hours – and just 30 miles later – Wise gave up and landed in Crawfordsville, Indiana. A piece of mail from Wise’s first flight has survived over the decades and now resides at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. The letter bearing a 3-cent stamp (about 80 cents in today’s buying power) was sent to the address: “W H Munn, No. 24 West 26 St., N York City.”

- The mail had only gone partway by air but was ignominiously put on a train to New York City to assure the swift completion of its appointed round. (The Lafayette Daily Courier mocked the flight as “trans-county-nental.”)

- A month later, Wise tried again. This time he made it as far as Henderson, New York – flying nearly 800 miles. A storm forced a crash landing, and he lost the mail in the crash.

- On June 14, 1910, Representative Morris Sheppard of Texas introduced a bill to authorize the Postmaster General to investigate the feasibility of “an aeroplane or airship mail route.” The bill died in committee. The New York Telegraph deemed airmail service a fanciful dream, predicting that, when it was offered: “Love letters will be carried in a rose-pink aeroplane, steered by Cupid’s wings and operated by perfumed gasoline. … [and] postmen will wear wired coat tails, and on their feet will be wings.”

- Aviator Earle Ovington had the distinction of piloting the first history-making flight, on September 23, 1911. The pilots made daily flights from Garden City Estates to Mineola, New York, dropping mailbags from the plane to the ground where they were picked up by Mineola’s Postmaster, William McCarthy.

- In 1913, 22-year-old Katherine Stinson became the first woman to fly the U.S. Mail when she dropped mailbags from her plane at the Montana State Fair. Stinson captivated audiences worldwide with her fearless feats of aerial derring-do. In 1918, she became the first woman to fly both an experimental mail route from Chicago to New York and the regular route from New York to Washington, D.C.

- Pilots followed landmarks on the ground; in fog they flew blind. Unpredictable weather, unreliable equipment, and inexperience led to frequent crashes. Gradually, through trial and error and personal sacrifice, U.S. Air Mail Service employees developed reliable navigation aids and safety features for planes and pilots.

- In 1916, Congress finally authorized the use of $50,000 from steamboat and powerboat service appropriations for airmail experiments. The Department advertised for bids for contract service in Massachusetts and Alaska but received no acceptable responses.

- Congress authorized airmail postage of 24 cents per ounce, including special delivery. The rate was lowered to 16 cents on July 15, 1918, and to 6 cents on December 15 (without special delivery).

- On February 22, 1921, the first daring, round-the-clock, transcontinental airmail flight started out with four planes. Two westbound planes left New York’s Hazelhurst Field while two eastbound planes left San Francisco. One of the westbound trips abruptly ended when icing forced the pilot down in a Pennsylvania field. The other was halted by a snowstorm in Chicago. One of the eastbound pilots fared even worse — William E. Lewis crashed and died near Elko, Nevada. The mail was salvaged and loaded onto another eastbound plane.

- It was after dark when the airmail reached North Platte, Nebraska, and pilot Jack Knight was ready to fly the next leg of the relay, to Omaha. A former Army flight instructor, Knight looked bad and felt worse, suffering a broken nose and bruises from a crash landing the week before in Wyoming. He had flown to Omaha many times — but never at night.

- Knight’s first taste of night-flying was nerve-wracking. Residents of the towns below lit bonfires to help mark the route. As the weather worsened, Knight set down in Omaha, wind-chilled, famished and exhausted. Then he got more bad news: the pilot scheduled to fly the next leg, to Chicago, was a no-show. Though the route was unfamiliar, Knight volunteered to fly the mail to Chicago himself.

- Between Omaha and Chicago lay a refueling stop in Iowa City, which Knight had never seen in the daytime, let alone at night in a snowstorm. There were no bonfires or beacons marking the airfield — the ground crew had gone home, assuming the flight had been canceled — but by some miracle Knight found it. He buzzed the field until the night watchman heard his airplane and lit a flare. After landing and refueling he was back in the cockpit. He touched down at Maywood Field, outside Chicago, at 8:40 a.m. The mailbags were quickly loaded onto a plane bound for Cleveland and then the final stretch to New York.

- The mail from San Francisco reached New York in record time — 33 hours and 20 minutes. Newspapers hailed Knight as the “hero who saved the airmail.” Congress, which had debated eliminating funding for airmail, instead increased it.

- To better its delivery time on long hauls and entice the public to use airmail, the Department’s long-range plans called for a transcontinental air route from New York to San Francisco. The first legs of this transcontinental route — from New York to Cleveland with a stop at Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, then from Cleveland to Chicago, with a stop at Bryan, Ohio — opened in 1919. A third leg opened in 1920 from Chicago to Omaha, via Iowa City, and feeder lines were established from St. Louis and Minneapolis to Chicago.

- The last transcontinental segment — from Omaha to San Francisco, via North Platte, Nebraska; Cheyenne, Rawlins, and Rock Springs in Wyoming; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Elko and Reno in Nevada — opened on September 8, 1920. Initially, mail was carried on trains at night and flown by day. Still, the service was 22 hours faster than the cross-country all-rail time.

- To prepare for night flying, the Post Office Department equipped its planes with luminescent instruments, navigational lights, and parachute flares. In 1923, it began building a lighted airway along the transcontinental route, to guide pilots at night. The first section completed was Chicago to Cheyenne, 885 miles.

- The now famous 5-cent airmail stamp issued on July 25, 1928, depicted the beacon light tower at the emergency airmail landing field near Sherman, Wyoming.

- In 1922 and 1923, the Department was awarded the Collier Trophy for important contributions to the development of aeronautics, especially in safety and for demonstrating the feasibility of night flights.

- The Department extended the lighted airway eastward to Cleveland and westward to Rock Springs, Wyoming, in 1924. In 1925, the lighted airway stretched from New York to Salt Lake City.

- Regular cross-country through service, with night flying, began on July 1, 1924. In 1926, the trip from New York to San Francisco included 15 stops for service and the exchange of mail. Pilots and planes changed six times en route, at Cleveland, Chicago, Omaha, Cheyenne, Salt Lake City, and Reno. The longest leg was between Omaha and Cheyenne, 476 miles; the shortest, 184 miles, was between Reno and San Francisco.

- Before Charles Lindbergh made his record-breaking solo transatlantic flight in 1927, he flew the mail. Lindbergh was the chief pilot for the Robertson Aircraft Corporation, which held the contract to provide airmail service between Chicago and St. Louis beginning April 15, 1926.

- As commercial airlines took over, the Department transferred its lights, airways, and radio service to the Department of Commerce, including 17 fully equipped stations, 89 emergency landing fields, and 405 beacons. Terminal airports, except government properties in Chicago, Omaha, and San Francisco, were transferred to the municipalities in which they were located.

- Airplanes were used to transport mail internationally with the establishment of routes from Seattle to Victoria, British Columbia, on October 15, 1920, and from Key West, Florida, to Havana, Cuba, beginning November 1, 1920. The Havana route was discontinued in 1923, but resumed on October 19, 1927, marking the beginning of regularly scheduled international airmail service.

- Transpacific airmail routes began operating on November 22, 1935, with FAM Route 14, from San Francisco via Hawaii, Midway, Wake, and Guam to the Philippines. Airmail service was extended to Hong Kong on April 21, 1937; to New Zealand on July 12, 1940; to Singapore on May 3, 1941; to Australia on January 28, 1947; and to China on July 15, 1947.

- Transatlantic airmail routes connected the United States with Europe beginning May 20, 1939, with the 29-hour flight of Pan American Airways’ Yankee Clipper from New York to Marseilles, France, via Bermuda, the Azores, and Portugal. That same year, on June 24, a route was inaugurated between New York and Great Britain by way of Newfoundland, Greenland, and Iceland.

- On December 6, 1941, direct airmail service to Africa was made possible by the inauguration of a route from Miami via Rio de Janeiro to the Belgian Congo. Though interrupted during WWII, improvements in aviation fostered the rapid expansion of international airmail routes in the postwar years.

- On October 4, 1958, a jet airliner was used to transport mail between London and New York for the first time, cutting the transatlantic trip from 14 hours to 8.

- Airmail as a separate class of domestic mail officially ended on May 1, 1977, although in practice it ended in October 1975, when the Postal Service announced that First-Class postage — which was three cents cheaper — would buy the same or better level of service. By then, transportation patterns had changed, and most First-Class letters were already zipping cross-country via airplane.

- Airmail as a separate class of international mail ended on May 14, 2007, when rates for the international transportation of mail by surface methods were eliminated.

- That simple “send” button we push was created by Ray Tomlinson, generally credited as having sent the first email across a network, initiating the use of the “@” sign to separate the names of the user and the user’s machine in 1971, when he sent a message from one Digital Equipment Corporation DEC-10 computer to another DEC-10.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

DO YOU LIKE CONTESTS?

Me, too.

As you may know the Kowalski Heat Treating logo finds its way

into the visuals of my Friday posts.

I. Love. My. Logo.

One week there could be three logos.

The next week there could be 15 logos.

And sometimes the logo is very small or just a partial logo showing.

But there are always logos in some of the pictures.

So, I challenge you, my beloved readers, to count them and send me a quick email with the total number of logos in the Friday post.

On the following Tuesday I’ll pick a winner from the correct answers

and send that lucky person some great KHT swag.

So, start counting and good luck!

Oh, and the logos at the very top header don’t count.

Got it? Good. :-))))

Have fun!!

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

DO YOU LIKE CONTESTS?

Me, too.

As you may know the Kowalski Heat Treating logo finds its way

into the visuals of my Friday posts.

I. Love. My. Logo.

One week there could be three logos.

The next week there could be 15 logos.

And sometimes the logo is very small or just a partial logo showing.

But there are always logos in some of the pictures.

So, I challenge you, my beloved readers, to count them and send me

a quick email with the total number of logos in the Friday post.

On the following Tuesday I’ll pick a winner from the correct answers

and send that lucky person some great KHT swag.

So, start counting and good luck!

Oh, and the logos at the very top header don’t count.

Got it? Good. :-))))

Have fun!!

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!