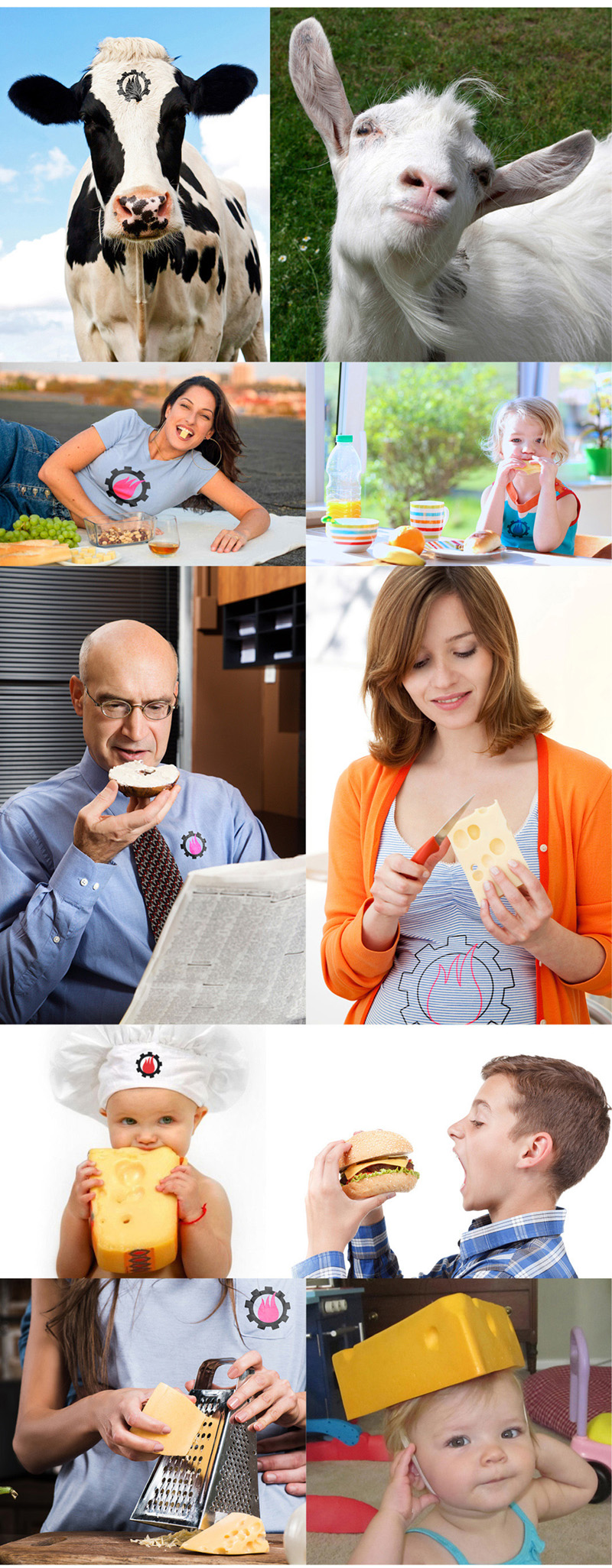

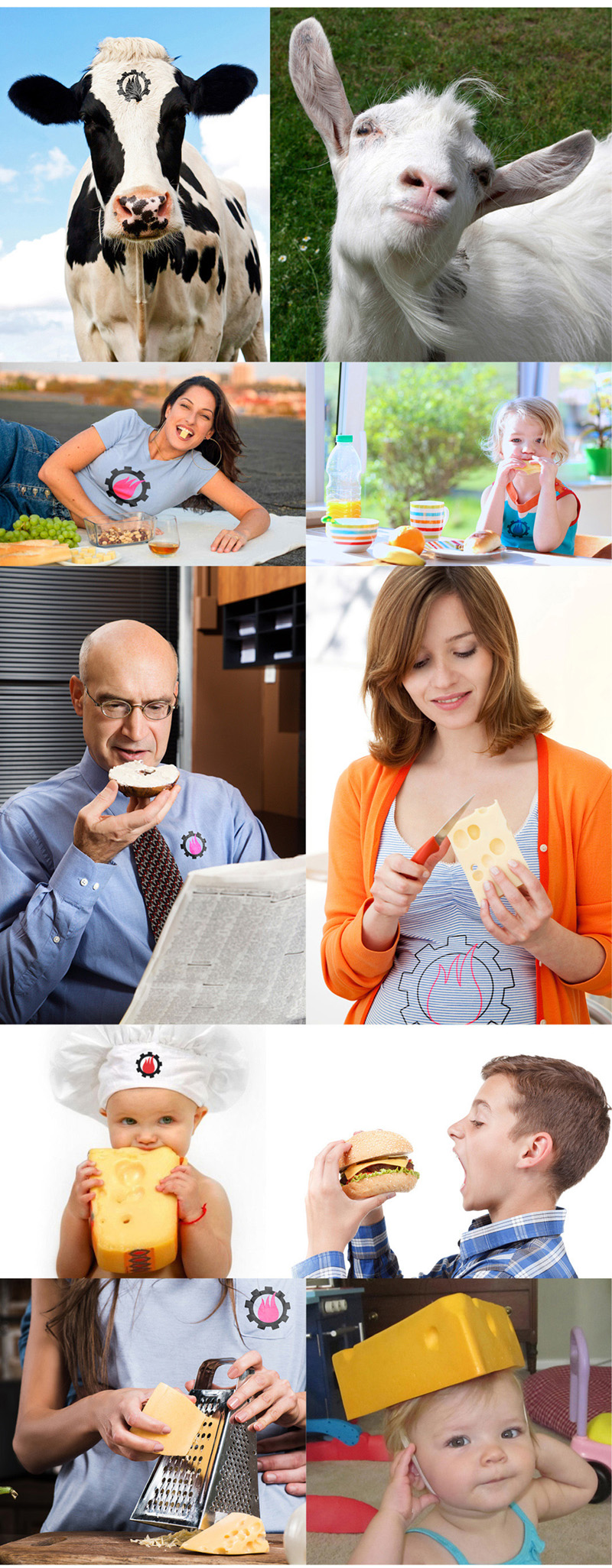

Cheese starts with Cow or goat milk mostly. Although other animals get into the act, too. (read on to find out what animals) But it’s just fun and nutritious to eat cheese. Spread it, cut bites, throw a couple of slices on a sandwich. The uses are many. And it’s all enjoyable. People are so passionate about cheese that an industry of clothing, costumes and jewelry has grown around the stuff. Me? I’ll eat it any way I can get it. See that picture near the bottom? That’s my head. I had the x-ray just before lunch last week and if you look really carefully, you’ll see what I was thinking. The picture at the bottom is what I had for lunch that day. :))))

Cheese. And my love of food. A partnership of devotion and enjoyment. Last weekend, while grilling one of my perfect hamburgers, (see prior KHT Blog) I ran into the house to grab some cheese to put on top of my seared beauties. I paused with the refrigerator door open, trying to satisfy my tastebuds – let’s see, what to choose… American, cheddar, swiss, smokey, pepperjack, blue, mozzarella, Kraft Singles (how do they get those little babies into the plastic wrapper anyway?) or one of my childhood wonders of the world – Velveeta – yikes. (what’s really inside that silver foil block of gold anyway – and who doesn’t remember using Mom’s wire cheese cutter and slicing off a big hunk of gooey love). Talk about a PIA (pain in the @%$) Job! I picked sharp cheddar and must admit it was perfecto! Of course, there are countless types of cheese, all of which with their own distinct textures and flavors. I’m learning that most good cheeses start out with the same star ingredient: milk. Variations include cow, sheep, goat, buffalo (and yep – camel, yak, and even horse). So, I decided to write a bit about cheese. Today’s blog is the detail on how it’s made – future blogs will explore flavors and techniques from around the world – along with some yummy recipes. Thanks to sclyderweaver.com for the step-by-step details, and YouTube and Cricketer Farm for the fun production videos (I’m still amazed how much handwork goes into some cheese production). Enjoy, and be sure to make a “toasted” (or grilled) cheese sandwich this weekend. If you have a personal recipe, please share: skowalski@khtheat.com.

Fun Production Video

Great Cheese Guide

Cheese Joke: What’s a basketball player’s favorite cheese? (Swish).

While all cheeses have milk in common, the type of milk can differ from cheese to cheese. Some common types of milk used in cheese making include:

- Cow’s milk: Most cheeses are made with cow’s milk. This is due in part to the wide availability of cow’s milk and the fact that it offers optimal amounts of fat and protein. Some examples of cow’s milk cheeses include cheddar, swiss and gouda, among many others.

- Sheep’s milk: Sheep’s milk isn’t commonly enjoyed as a beverage since it’s so high in lactose, but it makes an excellent base for cheese. Some popular types of sheep’s milk cheeses are feta, Roquefort, manchego and petit basque.

- Goat’s milk: Goat’s milk is also used to make some delicious cheeses, with a distinctive tangy flavor. Goat’s milk cheese is known in French as chèvre. In addition to fresh chèvre, other examples of goat’s milk cheeses include Le Chevrot and French Bucheron.

- Buffalo milk: Water buffalo milk is not a common cheese ingredient, but it has made a name for itself in the world of cheese making as the traditional choice for mozzarella. (most mass-produced mozzarella today is made with cow’s milk).

- Bit Obscure: Camel milk is common to make South Africa caracane cheese. Horse and yak.

– Milk doesn’t turn into delicious cheese on its own. Another important ingredient in cheese is a coagulant, which helps the milk turn into curds. The coagulant may be a type of acid or, more commonly, rennet. Rennet is an enzyme complex that is genetically engineered through microbial bioprocessing. Traditional rennet cheeses are actually made with rennin, the enzyme rennet is meant to replicate. Rennin, also known as chymosin, is an enzyme that is naturally produced in the stomachs of calves and other mammals to help them digest milk.

– Milk and coagulant are the main components of cheese, but cheese can also include sources of flavoring, such as salt, brine, herbs, spices and even wine. Some cheeses may be made with identical ingredients, but the end product will differ based on different aging processes.

– It’s a natural process that requires some help from artisans, known as fromagers or, simply, cheesemakers. Another term you may hear is a cheesemonger, but this technically refers to someone who sells cheese.

– The cheese-making process comes down to 10 essential steps:

STEP 1: PREPARING THE MILK

Since milk is the star of the show, to make cheese just right, you need your milk to be just right. “Just right” will differ from cheese to cheese, so many cheesemakers start by processing their milk however they need to in order to standardize it. This may involve manipulating the protein-to-fat ratio. It also often involves pasteurization or a more mild heat treatment (we like this step!!) Heating the milk kills organisms that could cause the cheese to spoil and can also prime the milk for the starter cultures to grow more effectively. Once the milk has been heat treated or pasteurized, it is cooled to 90°F so it is ready for the starter cultures. If a cheese calls for raw milk, it will need to be heated to 90°F before adding the starter cultures. See how all things require us heat treaters!!

STEP 2: ACIDIFYING THE MILK

The next step in the cheese-making process is adding starter cultures to acidify the milk. If you’ve ever tasted sour milk, then you know that left long enough, milk will acidify on its own. However, there is any number of bacteria that can grow and sour milk. Instead of letting milk sour on its own, the modern cheese-making process typically standardizes this step. Cheesemakers add starter and non-starter cultures to the milk that acidify it. The milk should already be 90°F at this point, and it must stay at this temperature for approximately 30 minutes while the milk ripens. During this ripening process, the milk’s pH level drops, and the flavor of the cheese begins to develop.

STEP 3: CURDLING THE MILK

The milk is still liquid milk at this point, so cheesemakers need to start manipulating the texture. The process of curdling the milk can also happen naturally. In fact, some nursing animals, such as calves, piglets or kittens, produce the rennin enzyme in their stomachs to help them digest their mother’s milk. Cheesemakers cause the same process to take place in a controlled way. In the past, natural rennin was typically the enzyme of choice for curdling the milk, but cheesemakers today usually use rennet, the lab-created equivalent. This reaction allows the milk to form coagulated lumps, known as curds. As the solid curd forms, a liquid byproduct remains, known as whey.

STEP 4: CUTTING THE CURD

The curds and whey mixture is allowed to separate and ferment until the pH reaches 6.4. At this point, the curd should form a large coagulated mass in the cheese-making vat. Then, cheesemakers use long curd knives that can reach the bottom of the vat to cut through the curds. Cutting the curd creates more surface area on the curd, which allows the curds and why to separate even more. Cheesemakers usually make crisscrossing cuts vertically, horizontally and diagonally to break up the curd. The size of the curds after cutting can influence the cheese’s level of moisture – larger chunks of curd retain more moisture, leading to a moisture cheese, and smaller pieces of curd can lead to a drier cheese.

STEP 5: PROCESSING THE CURD

After being cut, the curd continues to be processed. This might involve cooking the curds, stirring the curds or both. All of this processing is still aimed at the same goal of separating the curds and whey. In other words, the curds continue to acidify and release moisture as they are processed. The more the curds are cooked and stirred, the drier the cheese will be. Another way curd can be processed at this stage is through washing. Washing the curd means replacing whey with water. This affects the flavor and texture of the cheese. Washed curd cheeses tend to be more elastic and have a nice, mild flavor. Some examples of washed curd cheeses are gouda, havarti and Swedish fontina.

STEP 6: DRAINING THE WHEY

At this point, the curds and whey should be sufficiently separated, so it’s time to remove the whey completely. This means draining the whey from the vat, leaving only the solid chunks of curd. These chunks could be big or small, depending on how finely the curd has been cut. With all the whey drained, the curd should now look like a big mat. There are different means of draining whey. In some cases, cheesemakers allow it to drain off naturally. However, especially when it comes to harder cheeses that require a lower moisture content, cheesemakers are likely to get help from a mold or press. Putting pressure on the curd compacts and forces more whey out.

STEP 7: CHEDDARING THE CHEESE

With the whey drained, the curd should form a large slab. For some cheeses, another step remains to remove even more moisture from the curd. This step is known as cheddaring. After cutting the mat of curd into sections, the cheesemaker will stack the individual slabs of curd. Stacking the slabs puts pressure on them, forcing out more moisture. Periodically, the cheesemaker will repeat the process, cutting up the slabs of curd again and restacking them. The longer this process goes on, the more whey is removed from the curd, resulting in a denser, more crumbly finished cheese texture. Fermentation also continues during the cheddaring process. Eventually, the curd should reach a pH of 5.1 to 5.5. When it’s ready, the cheesemaker will mill the curd slabs, producing smaller pieces.

STEP 8: SALTING THE CHEESE

The curd is now beginning to look more like cheese in its final form. To add flavor, cheese makers can salt or brine the cheese at this point. This can either involve sprinkling on dry salt or submerging the cheese into brine. An example of a cheese that gets soaked in brine is mozzarella. Drier cheeses will be dry salted. Some cheeses have flavor added in other forms as well. Some examples of spices that find their way into some types of cheese are black pepper, horseradish, garlic, paprika, habanero and cloves. Cheese can also contain herbs, such as dill, basil, chives or rosemary. The options for flavoring cheeses are endless. For many cheeses, though, the focus is simply on developing the natural flavors of the cheese and adding salt to intensify those flavors.

STEP 9: SHAPING THE CHEESE

There are no more ingredients to add to the cheese at this point, so it’s ready to be shaped. This is where the final product really begins to reveal itself. Even with so much moisture removed from the curd, it is still malleable and soft. Therefore, cheesemakers are able to press the curd into molds to create standardized shapes. Molds can take the form of baskets or hoops. Baskets are molds that are only open on one end, and hoops are bottomless molds, meaning they only wrap around the sides of the curd. In either case, the milled curd mixture is pressed into the mold and left there for a certain amount of time to solidify into the right shape. These molds are usually round or rectangular.

STEP 10: AGING THE CHEESE

For some cheeses, the process is already finished, but for many cheeses, what’s known as aging remains. Aging should occur in a controlled, cool environment. As the cheese ages, molecular changes take place that cause the cheese to harden and the flavor to intensify. The aging process can take anywhere from a few days to many years. In some cases, mold develops, which adds unique color and flavor to the cheese. Once the cheese has finished aging, it is finally ready to be enjoyed by consumers. Cheeses can be sold in whole weels or blocks or by the wedge. When you know how much time, effort and care went into making your favorite cheese, it’s likely to taste even more delicious.

WHAT ABOUT “FRESH” CHEESE?

Fresh cheeses tend to be smooth, creamy and mild in flavor. There is one main difference that separates fresh cheese like feta, ricotta or fresh mozzarella, from other cheeses — they are not aged. Fresh cheeses must still go through the bulk of the steps we outlined above to varying degrees. If all you did was drain some of the whey off after initially forming curds and whey, you would have cottage cheese. For other fresh cheeses, you must continue to strain the curds to remove more moisture and pack the cheese into a shape. Making fresh cheese is a simpler process, so some home cooks attempt this type of cheese making in their own kitchens.

HOW IS CHEESE AGED?

Aging cheese doesn’t just mean leaving it lying around for a while. It is a carefully controlled and timed process, and even subtle changes can affect the texture and taste of the finished cheese. In general, cheeses are aged in cool environments with relatively high humidity levels. Another term for aging when it comes to cheese is ripening. There are two basic types of ripening that can take place:

- Interior-ripened cheeses are coated with an artificial rind of wax or some other material to protect the surface. This causes the aging process to occur from the inside out. Two common examples of interior-ripened cheese are cheddar and swiss.

- Surface-ripened cheeses are not sealed off on the outside, so a natural rind develops with the help of bacteria being introduced. This process causes the cheese to age from the outside in. Brie and Muenster are two examples of surface-ripened cheese.

Beyond these basic distinctions, it’s helpful to understand the process that goes into aging specific categories of aged cheese, including red mold (also known as washed rind) cheese, white mold (or bloomy rind) cheese and blue cheese.

RED MOLD CHEESE

As the name suggests, red mold cheeses are covered in a reddish rind. Some popular types of red mold cheeses include French Morbier, Reblochon and Taleggio. Red mold cheeses are also often called washed rind cheeses, which hints at how they are aged. These cheeses are stored in a very humid environment and are washed frequently in some type of liquid, such as wine or a salty brine, for example. The thinner the cheese, the more the liquid will permeate and soften the cheese.

WHITE MOLD CHEESE

Cheesemakers spray or rub a white penicillin mold onto aging cheeses to create white mold cheeses, also known as bloomy rind cheeses. When these cheeses are done aging, they are covered in a fuzzy white mold. This process results in a soft cheese that is creamy and pasty in texture. The most popular type of white mold cheese is brie, which is loved for its silky smoothness and mild flavor. Some other examples include French Normandy Camembert, Le Chevrot and St. Marcellin.

BLUE CHEESE

Some aged cheese doesn’t just have mold on the rind but throughout the inside of the cheese, as well. Blue cheeses, like the ever-popular French Roquefort, creamy gorgonzola or English blue stilton contain streaks of blue or green mold and have a characteristically sharp flavor. First, mold spores are added to the cheese at some point during the cheese-making process. Then, during the aging process, cheesemakers encourage the mold to grow and spread throughout the cheese by poking air tunnels into it.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

DO YOU LIKE CONTESTS?

Me, too.

As you may know the Kowalski Heat Treating logo finds its way

into the visuals of my Friday posts.

I. Love. My. Logo.

One week there could be three logos.

The next week there could be 15 logos.

And sometimes the logo is very small or just a partial logo showing.

But there are always logos in some of the pictures.

So, I challenge you, my beloved readers, to count them and send me a

quick email with the total number of logos in the Friday post.

On the following Tuesday I’ll pick a winner from the correct answers

and send that lucky person some great KHT swag.

So, start counting and good luck!

Oh, and the logos at the very top header don’t count.

Got it? Good. :-))))

Have fun!!

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::