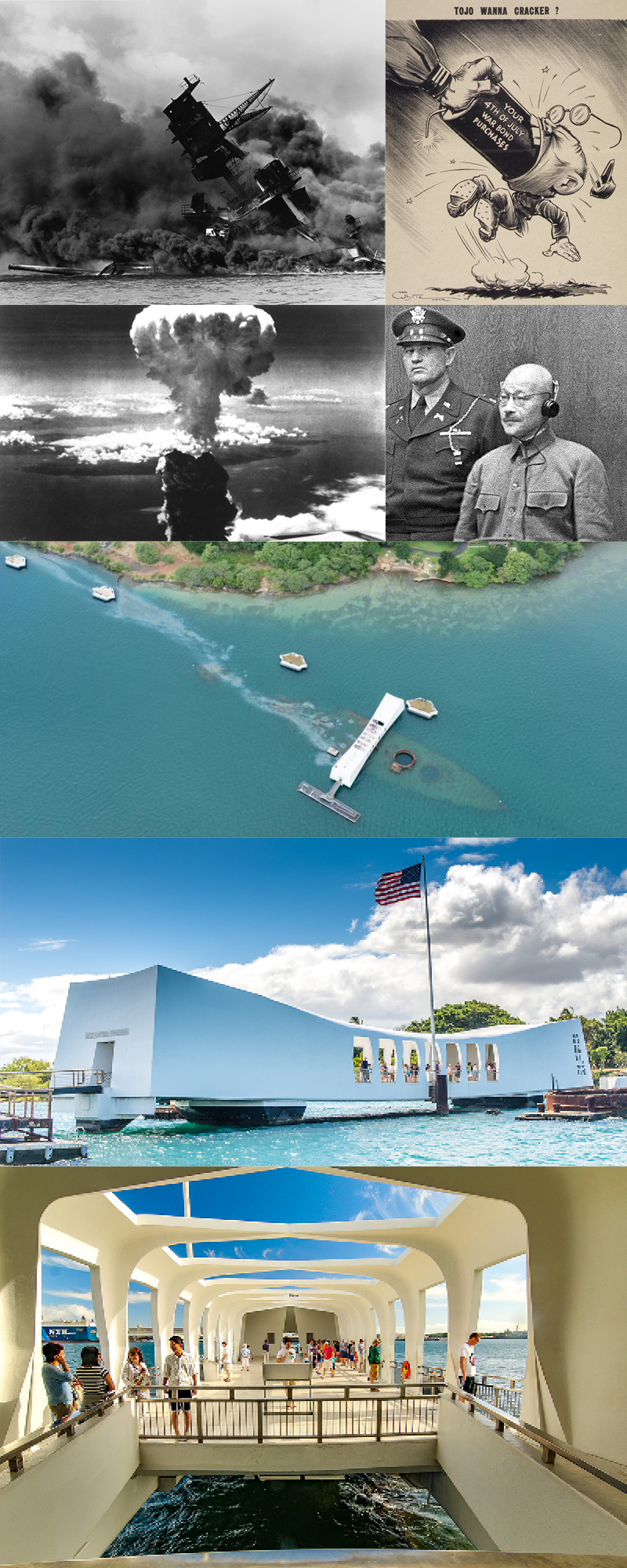

Live in Infamy

(top left) The USS Arizona during the attack on Hawaii. (top right) A war bonds poster. The headline says “Tojo Wanna Cracker?” (row 2 left) The bombs on Hiroshima (Aug. 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (Aug. 9, 1945) finally ended the war in the Pacific. (row 2 right) Hideki Tojo, prime minister of Japan (1941–44), at his war crimes trial in 1948, was hanged as a Class-A war criminal December 23, 1948. (the other three images) Three views of the USS Arizona Memorial in Hawaii.

Today we are reminded of “a date which will live in infamy” – the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Let us take a moment to respect those brave individuals who serve(d), better understand the events leading up to the event and reflect on the ongoing role of the US as the world’s peacekeeper. Special thanks to Wikipedia and Air and Space Museum for the insights.

- The attack on Pearl Harbor, many believe, can be traced back to the 1850’s, when U.S. Naval Captain Matthew C. Perry sailed to Japan and negotiated the opening of Japanese ports for trade. After more than 200 years of self-imposed isolation, Japan wanted to engage with the rest of the world and knew its fortunes lie outside its shores.

- To compete globally, Japan needed resources—a theme that persistently and eventually pushes the narrative of Pearl Harbor to its climax. Iron and coal were key natural resources in the steam era at the end of the 19th century but were not available in any significance on the Japanese island. Japan needed to look elsewhere for oil and vital manufacturing resources.

- Beginning around 1894, Japan engaged in war with China and in 1904 with Russia to secure more resources. A 1905 win against the Russian Navy shocked the world and alerted the U.S. that they needed to be prepared for new relations with a more aggressive Japan.

- As early as 1911, the U.S. Navy drafted plans for dealing with a possible war with Japan, known as War Plan Orange. The 1921 Washington Naval Treaty set out to prevent expensive naval building races between nations, but limited Japan to a much smaller navy than the U.S., a result that further soured the relationship between the two countries.

- The relationship between the two countries was cordial enough that they remained trading partners. Tensions did not seriously grow until Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Over the next decade, Japan expanded into China, leading to the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. Japan spent considerable effort trying to isolate China and endeavored to secure enough independent resources to attain victory on the mainland. The “Southern Operation” was designed to assist these efforts.

- Starting in December 1937, events such as the Japanese attack on USS Panay, the Allison incident, and the Nanking Massacre swung Western public opinion sharply against Japan. Fearing Japanese expansion, the United States, United Kingdom, and France assisted China with loans for war supply contracts. The goal was simple – keep Japan at bay.

- In 1940, Japan invaded French Indochina, attempting to stymie the flow of supplies reaching China. The United States halted shipments of airplanes, parts, machine tools, and aviation gasoline to Japan, which the latter perceived as an unfriendly act. The United States did not stop oil exports, however, partly because of the prevailing sentiment in Washington: given Japanese dependence on American oil, such an action was likely to be considered an extreme provocation.

- In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the Pacific Fleet from San Diego to Hawaii. He also ordered a military buildup in the Philippines, taking both actions in the hope of discouraging Japanese aggression in the Far East. Because the Japanese high command was (mistakenly) certain any attack on the United Kingdom’s Southeast Asian colonies, including Singapore, would bring the U.S. into the war, a devastating preventive strike appeared to be the only way to prevent American naval interference.

- In September 1940, Japan aligned with Germany and Italy. Japan hoped the war would result in a boon of new resources and saw the alignment as a way to push back against the U.S. embargos. If America wanted to declare war on Japan, they would also have to declare war on Germany meaning a fight across two oceans.

- An invasion of the Philippines was also considered necessary by Japanese war planners. The U.S. War Plan Orange had envisioned defending the Philippines with an elite force of 40,000 men; this option was never implemented due to opposition from Douglas MacArthur, who felt he would need a force ten times that size. By 1941, U.S. planners expected to abandon the Philippines at the outbreak of war.

- The U.S. finally ceased oil exports to Japan in July 1941, following the seizure of French Indochina after the Fall of France, in part because of new American restrictions on domestic oil consumption. Because of this decision, Japan proceeded with plans to take the oil-rich Dutch East Indies. On August 17, Roosevelt warned Japan that America was prepared to take opposing steps if “neighboring countries” were attacked. The Japanese were faced with a dichotomy—either withdraw from China and lose face or seize new sources of raw materials in the resource-rich European colonies of Southeast Asia.

- The U.S. believed that Japan would run out of necessary resources in six months and would have to agree to negotiations or cease military action. Japan did the same math and realized they needed to act. Japan began to plan the attack on Pearl Harbor.

- Many within the Japanese military were wary of the risks—Japanese carriers did not have the range to make it to Pearl Harbor and would need to refuel at sea, a maneuver that was unfamiliar to their navy. But to Japan, the potential reward outweighed the risks. They believed an attack on the U.S. would prevent America from entering the war for up to six months. In that time, Japan could shift the balance of power and take Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. Japan also hoped the attack would demoralize the United States into inaction.

- The Japanese Marshal Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto knew that to be successful secrecy was key. Few within the military were aware of what was conspired. Japanese carriers would take an extremely northern path to avoid shipping routes, and while travelling they were under complete radio silence. Even ship-to-ship communication was done using flags or blinker lights.

- The final orders to attack Pearl Harbor were delivered to the ships by hand before they sailed on November 26th. Burke noted that, at the time, the U.S. had only broken Japan’s diplomatic codes, not their naval codes. But even if the U.S. could read Japanese naval codes, there was no radio traffic to intercept.

- Japan set an internal deadline: If negotiations with the U.S. did not go as desired, Pearl Harbor would be attacked. They pushed the deadline to November 29th. Three days later, the Japanese high command sent the message, “Climb Mount Niitaka,” to tell the listening Japanese carrier force to proceed with the attack. War declaration communications were drafted and sent to the U.S. leadership, but never arrived on time.

- What unfolded in the days to come is the story we’re more familiar with—2,403 Americans were killed, 188 U.S. aircraft were destroyed, and the heart of the Pacific Fleet was left sitting on the harbor’s bottom.

- Said Pearl Harbor curator Lawrence Burke said, “We can see why Americans should have anticipated war with the Japanese.” But the specifics of the attack were a surprise. The U.S. knew something was afoot but anticipated being attacked in the Philippines not Pearl Harbor. The U.S. knew the risks that Japan faced with an attack on Pearl and believed it to be impossible. And the U.S. did not believe that Japan was capable of planning and executing such an attack.

- To say that Pearl Harbor was a complete surprise, as most history books do, does not take into account the complex history and relationships between the U.S. and Japan leading up to the attack. The war with Japan was not a surprise, but the location and nature of the first strike was.

To learn more, visit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pearl_Harbor_looking_southwest-Oct41.jpg, and God bless the brave souls who lost their lives defending our great nation.

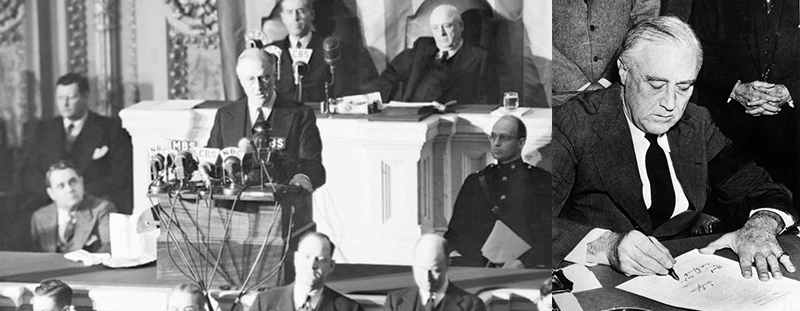

On December 8, 1941 President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivers his Declaration of War Address to congress and later officially signs it. WATCH HERE