Legend, Teamwork & The Impossible

Ever set a crazy goal … and then reach it? Ever been told “oh, that’s impossible”, then feeling larger than life when it happens? Ever convince a small group, that even though the goal is crazy (BHAG’s as the motivation experts like to call them today), you overcome the odds, and deliver. That drive, passion and purpose, lives everyday here at KHT – it’s the engine behind our PIA (Pain in the @%$) Jobs solutions – digging, testing, discovering and delivering. It’s an amazing feeling for sure. Last week a legend passed away at the age of 88 – Sir Roger Bannister, famously known as the first person to break the four-minute mile barrier, an accomplishment, at its time, most felt was “simply impossible”. Being a bit of a running junkie, I dug into the history books a bit, and found out some things I never knew – like the fact that two other runners were chasing the same dream and pushing Bannister to hit his goal – like the fact that Roger had a pack of runners help him during the race to set the correct pace – that prior to breaking the record, Roger finished far behind in the pack of runners in many of his previous races, was unsure of this ever happening, and even thought of not running at all that glorious day, and about a month later, another runner broke Mr. Bannister’s record time. Special thanks to The Guardian and Wikipedia and for the info, and congratulations Roger for reminding us all that sometimes, the impossible is possible.

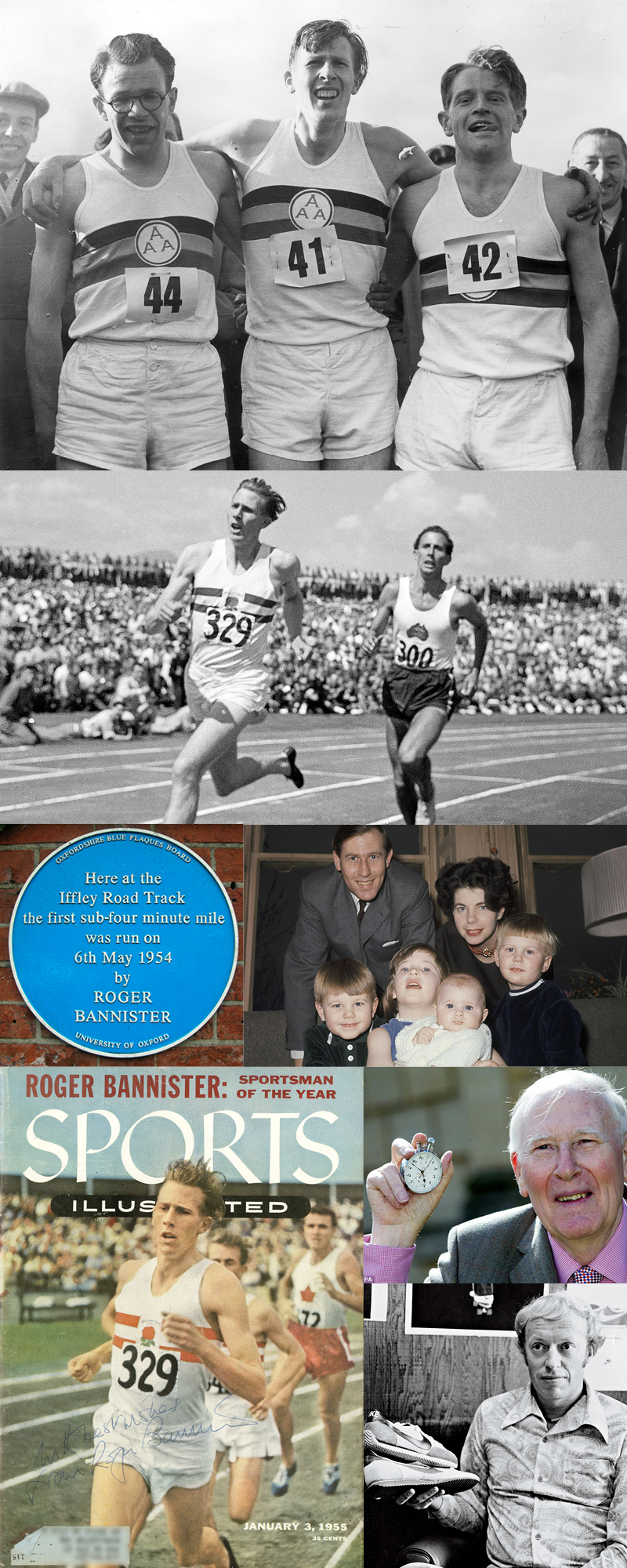

- Sir Roger Gilbert Bannister was a British middle-distance athlete, doctor and academic who ran the first sub-4-minute mile (3 minutes 59.4 seconds) on 6 May 1954 at Iffley Road track in Oxford, with Chris Chataway and Chris Brasher providing the pacing.

- Bannister was born in Harrow, England. He went to Vaughan Road Primary School in Harrow and continued his education at City of Bath Boys’ School and University College School, London; followed by medical school at the University of Oxford Exeter College and Merton College and at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School, now part of Imperial College London.

- Bannister started his running career at Oxford in the autumn of 1946 at the age of 17. He had never worn running spikes previously or run on a track. His training was light, even compared to the standards of the day, but he showed promise in running a mile in 1947 in 4:24.6 on only three weekly half-hour training sessions.

- He was selected as an Olympic “possible” in 1948 but declined as he felt he was not ready to compete at that level. Inspired to become a great miler by watching the 1948 Olympics, he set his training goals on the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki.

- In 1949, he improved in the 880 yards to 1:52.7 and won several mile races in 4:11. By 1950 Bannister saw more improvements as he finished a relatively slow 4:13 mile on 1 July with an impressive 57.5 last quarter. Then, he ran the AAA 880 in 1:52.1, losing to Arthur Wint, and then ran 1:50.7 for the 800 m at the European Championships on 26 August, placing third. Chastened by this lack of success, Bannister started to train harder and more seriously.

- His increased attention to training paid quick dividends, as he won a mile race in 4:09.9. In 1951 at the Penn Relays, Bannister broke away from the pack with a 56.7 final lap, finishing in 4:08.3. In his biggest test to date, he won a mile race on July 14 in 4:07.8 at the AAA Championships at White City before 47,000 people. The time set a meet record as he defeated defending champion Bill Nankeville in the process.

- Bannister avoided racing after the 1951 season until late in the spring of 1952, saving his energy for Helsinki and the Olympics. He ran an 880 on May 28 in 1:53.00, then a 4:10.6 mile time-trial in June, proclaiming himself satisfied with the results. At the AAA Championships, he skipped the mile and won the 880 in 1:51.5. Then, 10 days before the Olympic final, he ran a ¾ mile time trial in 2:52.9, which gave him confidence that he was ready for the Olympics as he considered the time to be the equivalent of a four-minute mile.

- His confidence soon dissipated as it was announced there would be semifinals for the 1500 m (equal to 0.932 miles) at the Olympics, and he knew that this favored runners who had much deeper training regimens than he did. The 1500 m final would prove to be one of the more dramatic in Olympic history. The race was not decided until the final meters, with Josy Barthel of Luxembourg prevailing in an Olympic-record 3:45.28 (3:45.1 by official hand-timing) and the next seven runners all under the old record. Bannister finished fourth, out of the medals, but set a British record of 3:46.30 in the process.

- After his relative failure at the 1952 Olympics, Bannister spent two months deciding whether to give up running. He set himself on a new goal: to be the first man to run a mile in under four minutes. Accordingly, he intensified his training and did hard intervals, a type of training that involves a series of low- to high-intensity workouts interspersed with rest or relief periods

- On 2 May 1953, he made an attempt on the British record at Oxford. Paced by Chris Chataway, Bannister ran 4:03.6, shattering Wooderson’s 1945 standard. “This race made me realize that the four-minute mile was not out of reach,” said Bannister.

- Other runners were making attempts at the four-minute barrier and coming close as well. American Wes Santee ran 4:02.4 in June, the fourth-fastest mile ever. And at the end of the year, Australian John Landy ran 4:02.0, and matched his time again early in 1954. Bannister had been following Landy’s and Santee’s attempts and was certain a rival would likely succeed, Bannister knew he had to make his attempt soon.

- The historic event took place on May 6, 1954 during a meet between British AAA and Oxford University at Iffley Road Track in Oxford, watched by about 3,000 spectators. With winds up to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h) before the event, Bannister had said twice that he favored not running, to conserve his energy and efforts to break the 4-minute barrier; he would try again at another meet. However, the winds dropped just before the race was scheduled to begin, and Bannister did run.

- The pace-setters from his major 1953 attempts, future Commonwealth Games gold medalist Chris Chataway and Olympic Games gold medalist Chris Brasher combined to provide pacing on this historic day. Bannister had begun his day at a hospital in London, where he sharpened his racing spikes and rubbed graphite on them so they would not pick up too much cinder ash. He took a mid-morning train from Paddington Station to Oxford, nervous about the rainy, windy conditions that afternoon.

- The race went off as scheduled at 6:00 pm, and Brasher and Bannister went immediately to the lead. Brasher, wearing No. 44, led both the first lap in 58 seconds and the half-mile in 1:58, with Bannister, No. 41, tucked in behind, and Chataway a stride behind Bannister. Chataway moved to the front after the second lap and maintained the pace with a 3:01 split at the bell. Chataway continued to lead around the front turn until Bannister began his finishing kick with about 275 yards to go, running the last lap in just under 59 seconds. Said Bannister, “The world seemed to stand still, or did not exist. The only reality was the next 200 yards of track under my feet. The tape meant finality – extinction perhaps. I felt at that moment that it was my chance to do one thing supremely well. I drove on, impelled by a combination of fear and pride.”

- The stadium announcer for the race was Norris McWhirter, (who went on to co-publish and co-edit the Guinness Book of Records). He excited the crowd by delaying the announcement of the time Bannister ran as long as possible.

“Ladies and gentlemen, here is the result of event nine, the one mile: first, number forty one, R. G. Bannister, Amateur Athletic Association and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, Oxford, with a time which is a new meeting and track record, and which—subject to ratification—will be a new English Native, British National, All-Comers, European, British Empire and World Record. The time was three…” (the roar of the crowd drowned out the rest of the announcement – “minutes, 59.4 seconds.”

- The claim that a four-minute mile was once thought to be impossible by “informed” observers was and is a widely propagated myth created by sportswriters. The reason the myth took hold was that four minutes was a round number which was slightly better (1.4 seconds) than the world record for nine years, longer than it probably otherwise would have been because of the effect of the Second World War in interrupting athletic progress in the combatant countries.

- Just 46 days later, on 21 June in Turku, Finland, Bannister’s record was broken by his Australian rival John Landy, with a time of 3 min 57.9 s, which the IAAF ratified as 3 min 58.0 s due to the rounding rules then in effect.

- On August 7, at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Vancouver, B.C., Bannister, running for England, competed against Landy for the first time in a race billed as “The Miracle Mile”. They were the only two men in the world to have broken the 4-minute barrier, with Landy still holding the world record. Landy led for most of the race, building a lead of 10 yards in the third lap (of four), but was overtaken on the last bend, and Bannister won in 3 min 58.8 s, with Landy 0.8 s behind in 3 min 59.6 s. Bannister and Landy have both pointed out that the crucial moment of the race was that at the moment when Bannister decided to try to pass Landy, Landy looked over his left shoulder to gauge Bannister’s position and Bannister burst past him on the right, never relinquishing the lead.

- Bannister went on that season to win the so-called metric mile, the 1500 m, at the European Championships in Bern, Switzerland, with a championship record in a time of 3 min 43.8 s. He retired from athletics late in 1954 to concentrate on his work as a junior doctor and to pursue a career in neurology.

- Bannister later became the first Chairman of the Sports Council (now called Sport England) and was knighted for this service in 1975. Under his aegis, central and local government funding of sports centers and other sports facilities was rapidly increased. He also initiated the first testing for use of anabolic steroids in sport.

- Retiring from athletics, Bannister spent forty years practicing medicine. He ultimately published more than 80 papers, mostly concerned with the autonomic nervous system, cardiovascular physiology, and multiple system atrophy. Bannister married the artist Moyra Jacobsson, daughter of the Swedish economist Per Jacobsson, who served as Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund. In 2011, Bannister was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and died on March 3, 2018 at the age of 88.

- On the 50th anniversary of running the sub-4-minute mile, Bannister was interviewed by the BBC’s sports correspondent Rob Bonnet. At the conclusion of the interview, Bannister was asked whether he looked back on the sub-4-minute mile as the most important achievement of his life. To the contrary, Bannister replied essentially that he instead saw his subsequent forty years of practicing as a neurologist and some of the new procedures he introduced as being more significant.

- For his efforts, Bannister was made the inaugural recipient of the Sports Illustrated Sportsperson of the Year award for 1954. Later runners inspired by Bannister and his achievement, included Phil Knight who says that Roger Bannister inspired him to start Nike.

- Today, according to The IAAF, the official body which oversees the records, Hicham El Guerrouj of Moracco is the current men’s record holder of the mile with his time of 3:43.13, while Russian Svetlana Masterkova has the women’s record of 4:12.56.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!