You Can Taste It

/0 Comments/in cookies, Friday Afternoon, Trivia /by Steve Kowalski

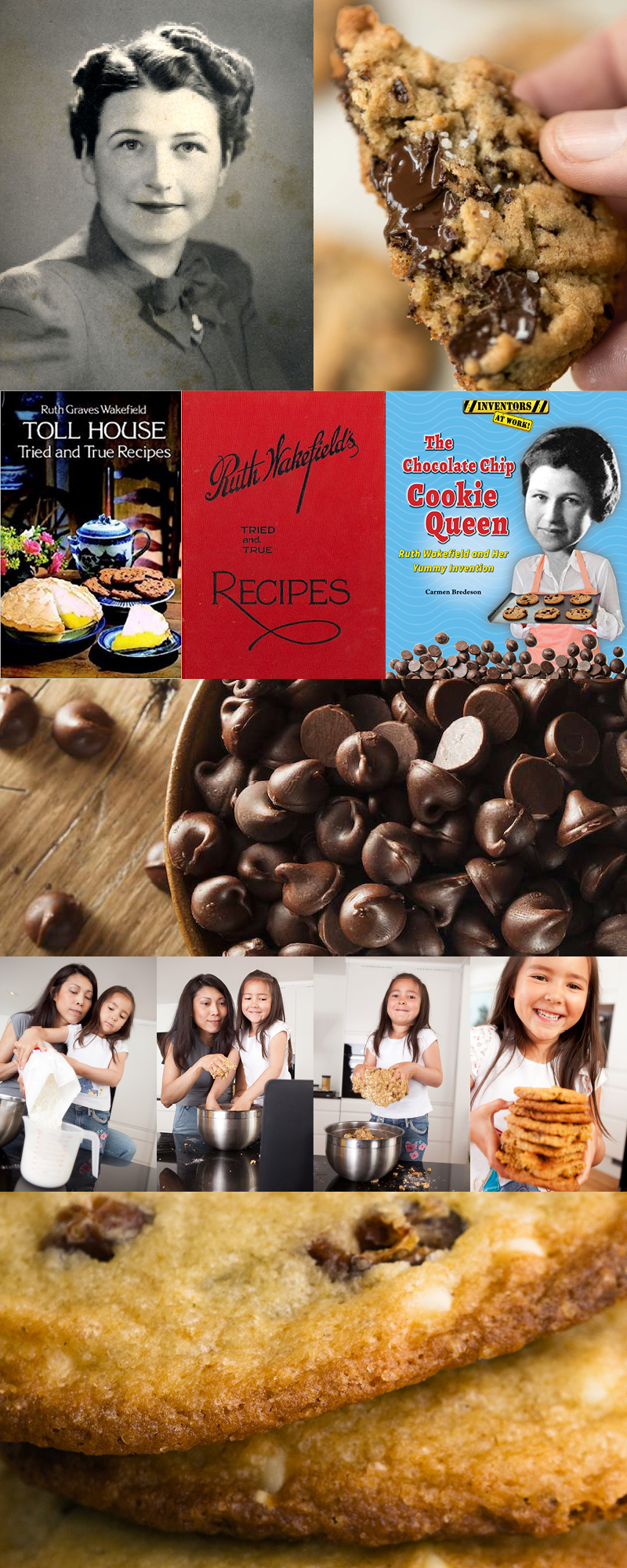

(top row) Ruth Graves Wakefield and her cookie discovery. (row two) Find the current iteration of Ruth Wakefield’s wonderful recipe book on Amazon; Find a copy the original cookbook on Ebay; And this book celebrating Ruth’s invention of the chocolate chip cookie on Amazon. (the rest) I wonder how many thousands of kids have had their first taste (pun intended) of cooking by baking these cookies. Ahhhh, the smell that fills the house. Mmmm, the taste. Love it!!

Here at KHT, we’re all about recipe’s. Mixing ingredients, fine tuning temperatures, and even experimenting to find just the right balance for your PIA (Pain in the #%$) Jobs. We love it, and just can’t get enough “tinkering” time to make sure every single load comes out great. The other day I had a craving that I just had to follow – to get a tasty chocolate chip cookie. Immediately I thought of the special women in my life, and their recipes – grandma Kowalski, my amazing wife Jackie, and the girls. Each have their own way of mixing ingredients, baking and serving chocolate chip cookies … and I love every one of them!! (especially with vanilla ice cream and hot fudge! of course). Since Jackie’s chocolate chip cookies don’t last very long in our house, I really like to snitch from the mixing bowl before they go into the oven! It made me search out the history of this incredible invention, and that took me to Ruth Wakefield some 80 years ago this year. Enjoy, and thanks to Wikipedia and Jon Michaud from The New Yorker for the insights. And, if you have a “family favorite”, send me the recipe to post … or better yet, a fresh box to share with the KHT gang.

- The chocolate chip cookie was invented in 1938 by the American chef Ruth Graves Wakefield. She invented the recipe during the period when she owned the Toll House Inn, in Whitman, Massachusetts, a popular restaurant that featured home cooking and tasty deserts.

- Created as an accompaniment to ice cream, her chocolate-chip cookie quickly became so celebrated that Marjorie Husted (a.k.a. Betty Crocker) featured it on her radio program. On March 20, 1939, Wakefield gave Nestlé the right to use her cookie recipe and the Toll House name – for the price of one dollar – (a dollar that Wakefield later said she never received, though she was reportedly given free chocolate for life and was also paid by Nestlé for work as a consultant).

- It is often incorrectly reported that she accidentally developed the cookie, and that she expected the chocolate chunks would melt, making chocolate cookies. In fact, she stated that she deliberately invented the cookie. She said, “We had been serving a thin butterscotch nut cookie with ice cream. Everybody seemed to love it, but I was trying to give them something different. So, I came up with the Toll House cookie using chopped up bits from a Nestlé semi-sweet chocolate bar. (the original recipe is called “Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookies.)

- Wakefield’s cookbook, Toll House Tried and True Recipes, was first published in 1936 by M. Barrows & Company, New York. The 1938 edition of the cookbook was the first to include the recipe “Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookie” which rapidly became a favorite cookie in American homes.

- During WWII, soldiers from Massachusetts who were stationed overseas shared the cookies they received in care packages from back home with soldiers from other parts of the United States. Soon, hundreds of soldiers were writing home asking their families to send them some Toll House cookies, and Wakefield was soon inundated with letters from around the world requesting her recipe. Thus began the nationwide craze for the chocolate chip cookie.

- In the postwar years, the chocolate-chip cookie followed the path taken by many American culinary innovations: from homemade to mass-produced, from kitchen counter to factory floor, from fresh to franchised. In the nineteen-fifties, both Nestlé and Pillsbury began selling refrigerated chocolate-chip-cookie dough in supermarkets. Nabisco, meanwhile, launched Chips Ahoy in 1963, its line of packaged cookies.

- The Baby Boom generation, which had been raised on the Toll House cookie, sought to recapture the original taste of these homemade treats in stores that sold fresh-baked cookies. Famous Amos, Mrs. Fields, and David’s Cookies all opened their first stores in the seventies and prospered in the eighties. By the middle of that decade, there were more than twelve hundred cookie stands in business across the country.

- Every bag of Nestlé chocolate chips sold in North America has a variation (butter vs. margarine is now a stated option) of her original recipe printed on the back. The original recipe was passed down as follows:

- 1 1/2 cups (350 mL) shortening

- 1 1/8 cups (265 mL) sugar

- 1 1/8 cups (265 mL) brown sugar

- 3 eggs

- 1 1/2 teaspoon (7.5 g) salt

- 3 1/8 cups (750 mL) of flour

- 1 1/2 teaspoon (7.5 g) hot water

- 1 1/2 teaspoon (7.5 g) baking soda

- 1 1/2 teaspoon (7.5 g) vanilla

- chocolate chips – 2 bars (7 oz.) Nestlé’s yellow label chocolate, semi-sweet, cut in pieces the size of a pea.

- Although the Nestlé’s Toll House recipe is widely known, every brand of chocolate chips, or “semi-sweet chocolate morsels” in Nestlé parlance, sold in the U.S. and Canada bears a variant of the chocolate chip cookie recipe on its packaging. Almost all baking-oriented cookbooks will contain at least one type of recipe.

- Practically all commercial bakeries offer their own version of the cookie in packaged baked or ready-to-bake forms. National chains sell freshly baked chocolate chip cookies in shopping malls and standalone retail locations and several businesses offer freshly baked cookies to their patrons to differentiate themselves from their competition.

- There is an urban legend about Neiman Marcus’ chocolate chip cookie recipe that has gathered a great deal of popularity over the years. The legend claims Newman Marcus charged a customer $250 for the recipe, rather than the $2.50 she had expected.

- Depending on the ratio of ingredients and mixing and cooking times, some recipes are optimized to produce a softer, chewy style cookie while others will produce a crunchy/crispy style. Regardless of ingredients, the procedure for making the cookie is fairly consistent in all recipes.

- The texture of a chocolate chip cookie is largely dependent on its fat composition and the type of fat used. A study done by Kansas State University showed that carbohydrate based fat-replacers were more likely to bind more water, leaving less water available to aid in the spread of the cookie while baking. This resulted in softer, more cake-like cookies with less spread.

- Common variations include M&M’s (a “party” cookie), chocolate-chocolate chip using a chocolate flavored dough, using white chocolate, peanut butter chips or macadamia nuts, and replacing the dough with a flavored version, such as peanut butter. Other variations include using other types of chocolate, nuts or oatmeal. There are also vegan versions with ingredient substitutions such as vegan chocolate chips, vegan margarine, and so forth.

- Other taste variaitons include the Chipwich, the Taste of Nature Cookie Dough Bite, and the Pookie (a pie coated with chocolate-chip-cookie dough). Perhaps none of these variations was more culinarily or culturally significant than the début, in 1984, of Ben & Jerry’s Chocolate Chip Cookie Dough ice cream – it took them five years to find a way to mechanize the process of hand-mixing the frozen cookie dough with the ice cream, but it proved profitable. By 1991, Chocolate Chip Cookie Dough replaced Heath Bar Crunch as the company’s bestselling product.

- If you google chocolate chip cookies or best chocolate chip cookie recipes/cookbooks, you get hundreds of choices (I suggest you try them all!) One of my favorites is The Great American Chocolate Chip Cookie Book: Scrumptious Recipes & Fabled History From Toll House to Cookie Cake Pie, by Carolyn Wyman.

- To honor the cookie’s creation in the state, on July 9, 1997, Massachusetts designated the chocolate chip cookie as the Official State Cookie, after it was proposed by a third-grade class from Somerset, Massachusetts.

- Nowadays, we’d expect the inventor of such an iconic bit of Americana to publish an autobiography and make regular appearances on the Food Network, but Wakefield didn’t grandstand. She and her husband sold the restaurant, in 1967, and she passed in 1977. The original Toll House restaurant burned down spectacularly on New Year’s Eve in 1984 and the spot is now home to a Wendy’s. The authorities in Whitman required the fast-food restaurant include a small museum to Wakefield and the Toll House on its premises.

Life is like a cup of tea – it’s all in how you make it!

/0 Comments/in Friday Afternoon, St. Patrick's Day, Trivia /by Steve KowalskiStephen O’Shannessy O’Brien McMurphy Patrick Michael O’Kowalski back again, with some fun sayings, blessings and inspirations straight out of Ireland for you to use this St. Patrick’s Day. So, pick your favorite sayings (email them to friends), get green, smile, laugh and look for your pot ‘o gold and lucky leprechauns. To our friends, families, customers, employees, vendors, partners, neighbors and loved ones – may all the blessings of Saint Patrick behold you, in this simple poem – (special thanks to irishcentral.com for all ye fun tidbits below).

Legend, Teamwork & The Impossible

/0 Comments/in Friday Afternoon, History, Trivia /by Steve Kowalski

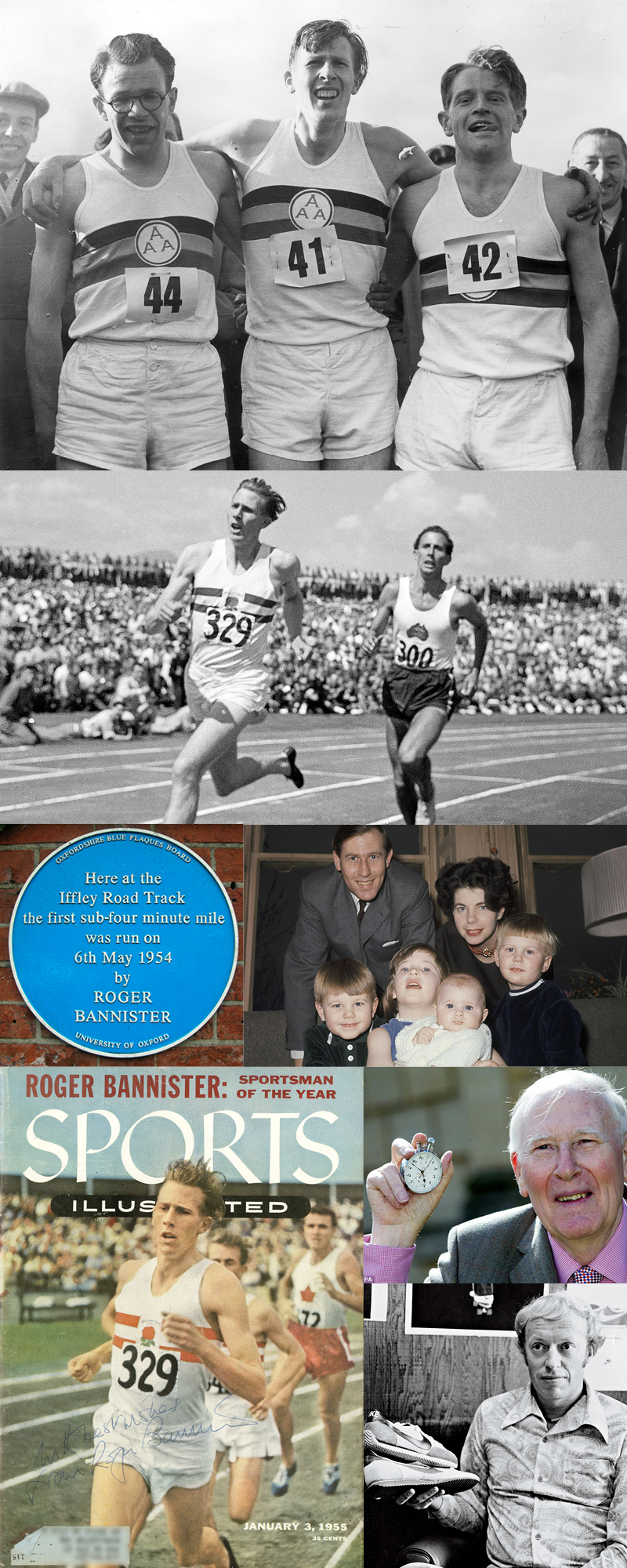

Ever set a crazy goal … and then reach it? Ever been told “oh, that’s impossible”, then feeling larger than life when it happens? Ever convince a small group, that even though the goal is crazy (BHAG’s as the motivation experts like to call them today), you overcome the odds, and deliver. That drive, passion and purpose, lives everyday here at KHT – it’s the engine behind our PIA (Pain in the @%$) Jobs solutions – digging, testing, discovering and delivering. It’s an amazing feeling for sure. Last week a legend passed away at the age of 88 – Sir Roger Bannister, famously known as the first person to break the four-minute mile barrier, an accomplishment, at its time, most felt was “simply impossible”. Being a bit of a running junkie, I dug into the history books a bit, and found out some things I never knew – like the fact that two other runners were chasing the same dream and pushing Bannister to hit his goal – like the fact that Roger had a pack of runners help him during the race to set the correct pace – that prior to breaking the record, Roger finished far behind in the pack of runners in many of his previous races, was unsure of this ever happening, and even thought of not running at all that glorious day, and about a month later, another runner broke Mr. Bannister’s record time. Special thanks to The Guardian and Wikipedia and for the info, and congratulations Roger for reminding us all that sometimes, the impossible is possible.

- Sir Roger Gilbert Bannister was a British middle-distance athlete, doctor and academic who ran the first sub-4-minute mile (3 minutes 59.4 seconds) on 6 May 1954 at Iffley Road track in Oxford, with Chris Chataway and Chris Brasher providing the pacing.

- Bannister was born in Harrow, England. He went to Vaughan Road Primary School in Harrow and continued his education at City of Bath Boys’ School and University College School, London; followed by medical school at the University of Oxford Exeter College and Merton College and at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School, now part of Imperial College London.

- Bannister started his running career at Oxford in the autumn of 1946 at the age of 17. He had never worn running spikes previously or run on a track. His training was light, even compared to the standards of the day, but he showed promise in running a mile in 1947 in 4:24.6 on only three weekly half-hour training sessions.

- He was selected as an Olympic “possible” in 1948 but declined as he felt he was not ready to compete at that level. Inspired to become a great miler by watching the 1948 Olympics, he set his training goals on the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki.

- In 1949, he improved in the 880 yards to 1:52.7 and won several mile races in 4:11. By 1950 Bannister saw more improvements as he finished a relatively slow 4:13 mile on 1 July with an impressive 57.5 last quarter. Then, he ran the AAA 880 in 1:52.1, losing to Arthur Wint, and then ran 1:50.7 for the 800 m at the European Championships on 26 August, placing third. Chastened by this lack of success, Bannister started to train harder and more seriously.

- His increased attention to training paid quick dividends, as he won a mile race in 4:09.9. In 1951 at the Penn Relays, Bannister broke away from the pack with a 56.7 final lap, finishing in 4:08.3. In his biggest test to date, he won a mile race on July 14 in 4:07.8 at the AAA Championships at White City before 47,000 people. The time set a meet record as he defeated defending champion Bill Nankeville in the process.

- Bannister avoided racing after the 1951 season until late in the spring of 1952, saving his energy for Helsinki and the Olympics. He ran an 880 on May 28 in 1:53.00, then a 4:10.6 mile time-trial in June, proclaiming himself satisfied with the results. At the AAA Championships, he skipped the mile and won the 880 in 1:51.5. Then, 10 days before the Olympic final, he ran a ¾ mile time trial in 2:52.9, which gave him confidence that he was ready for the Olympics as he considered the time to be the equivalent of a four-minute mile.

- His confidence soon dissipated as it was announced there would be semifinals for the 1500 m (equal to 0.932 miles) at the Olympics, and he knew that this favored runners who had much deeper training regimens than he did. The 1500 m final would prove to be one of the more dramatic in Olympic history. The race was not decided until the final meters, with Josy Barthel of Luxembourg prevailing in an Olympic-record 3:45.28 (3:45.1 by official hand-timing) and the next seven runners all under the old record. Bannister finished fourth, out of the medals, but set a British record of 3:46.30 in the process.

- After his relative failure at the 1952 Olympics, Bannister spent two months deciding whether to give up running. He set himself on a new goal: to be the first man to run a mile in under four minutes. Accordingly, he intensified his training and did hard intervals, a type of training that involves a series of low- to high-intensity workouts interspersed with rest or relief periods

- On 2 May 1953, he made an attempt on the British record at Oxford. Paced by Chris Chataway, Bannister ran 4:03.6, shattering Wooderson’s 1945 standard. “This race made me realize that the four-minute mile was not out of reach,” said Bannister.

- Other runners were making attempts at the four-minute barrier and coming close as well. American Wes Santee ran 4:02.4 in June, the fourth-fastest mile ever. And at the end of the year, Australian John Landy ran 4:02.0, and matched his time again early in 1954. Bannister had been following Landy’s and Santee’s attempts and was certain a rival would likely succeed, Bannister knew he had to make his attempt soon.

- The historic event took place on May 6, 1954 during a meet between British AAA and Oxford University at Iffley Road Track in Oxford, watched by about 3,000 spectators. With winds up to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h) before the event, Bannister had said twice that he favored not running, to conserve his energy and efforts to break the 4-minute barrier; he would try again at another meet. However, the winds dropped just before the race was scheduled to begin, and Bannister did run.

- The pace-setters from his major 1953 attempts, future Commonwealth Games gold medalist Chris Chataway and Olympic Games gold medalist Chris Brasher combined to provide pacing on this historic day. Bannister had begun his day at a hospital in London, where he sharpened his racing spikes and rubbed graphite on them so they would not pick up too much cinder ash. He took a mid-morning train from Paddington Station to Oxford, nervous about the rainy, windy conditions that afternoon.

- The race went off as scheduled at 6:00 pm, and Brasher and Bannister went immediately to the lead. Brasher, wearing No. 44, led both the first lap in 58 seconds and the half-mile in 1:58, with Bannister, No. 41, tucked in behind, and Chataway a stride behind Bannister. Chataway moved to the front after the second lap and maintained the pace with a 3:01 split at the bell. Chataway continued to lead around the front turn until Bannister began his finishing kick with about 275 yards to go, running the last lap in just under 59 seconds. Said Bannister, “The world seemed to stand still, or did not exist. The only reality was the next 200 yards of track under my feet. The tape meant finality – extinction perhaps. I felt at that moment that it was my chance to do one thing supremely well. I drove on, impelled by a combination of fear and pride.”

- The stadium announcer for the race was Norris McWhirter, (who went on to co-publish and co-edit the Guinness Book of Records). He excited the crowd by delaying the announcement of the time Bannister ran as long as possible.

“Ladies and gentlemen, here is the result of event nine, the one mile: first, number forty one, R. G. Bannister, Amateur Athletic Association and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, Oxford, with a time which is a new meeting and track record, and which—subject to ratification—will be a new English Native, British National, All-Comers, European, British Empire and World Record. The time was three…” (the roar of the crowd drowned out the rest of the announcement – “minutes, 59.4 seconds.”

- The claim that a four-minute mile was once thought to be impossible by “informed” observers was and is a widely propagated myth created by sportswriters. The reason the myth took hold was that four minutes was a round number which was slightly better (1.4 seconds) than the world record for nine years, longer than it probably otherwise would have been because of the effect of the Second World War in interrupting athletic progress in the combatant countries.

- Just 46 days later, on 21 June in Turku, Finland, Bannister’s record was broken by his Australian rival John Landy, with a time of 3 min 57.9 s, which the IAAF ratified as 3 min 58.0 s due to the rounding rules then in effect.

- On August 7, at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Vancouver, B.C., Bannister, running for England, competed against Landy for the first time in a race billed as “The Miracle Mile”. They were the only two men in the world to have broken the 4-minute barrier, with Landy still holding the world record. Landy led for most of the race, building a lead of 10 yards in the third lap (of four), but was overtaken on the last bend, and Bannister won in 3 min 58.8 s, with Landy 0.8 s behind in 3 min 59.6 s. Bannister and Landy have both pointed out that the crucial moment of the race was that at the moment when Bannister decided to try to pass Landy, Landy looked over his left shoulder to gauge Bannister’s position and Bannister burst past him on the right, never relinquishing the lead.

- Bannister went on that season to win the so-called metric mile, the 1500 m, at the European Championships in Bern, Switzerland, with a championship record in a time of 3 min 43.8 s. He retired from athletics late in 1954 to concentrate on his work as a junior doctor and to pursue a career in neurology.

- Bannister later became the first Chairman of the Sports Council (now called Sport England) and was knighted for this service in 1975. Under his aegis, central and local government funding of sports centers and other sports facilities was rapidly increased. He also initiated the first testing for use of anabolic steroids in sport.

- Retiring from athletics, Bannister spent forty years practicing medicine. He ultimately published more than 80 papers, mostly concerned with the autonomic nervous system, cardiovascular physiology, and multiple system atrophy. Bannister married the artist Moyra Jacobsson, daughter of the Swedish economist Per Jacobsson, who served as Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund. In 2011, Bannister was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and died on March 3, 2018 at the age of 88.

- On the 50th anniversary of running the sub-4-minute mile, Bannister was interviewed by the BBC’s sports correspondent Rob Bonnet. At the conclusion of the interview, Bannister was asked whether he looked back on the sub-4-minute mile as the most important achievement of his life. To the contrary, Bannister replied essentially that he instead saw his subsequent forty years of practicing as a neurologist and some of the new procedures he introduced as being more significant.

- For his efforts, Bannister was made the inaugural recipient of the Sports Illustrated Sportsperson of the Year award for 1954. Later runners inspired by Bannister and his achievement, included Phil Knight who says that Roger Bannister inspired him to start Nike.

- Today, according to The IAAF, the official body which oversees the records, Hicham El Guerrouj of Moracco is the current men’s record holder of the mile with his time of 3:43.13, while Russian Svetlana Masterkova has the women’s record of 4:12.56.

“Yea, That’s My Country too!”

/0 Comments/in Flag, Friday Afternoon, Music, Patriotism, Trivia /by Dan Fauver

(row one left) Francis Scott Key. (row one top right) The first sheet-music issue of “The Star-Spangled Banner” was printed by Thomas Carr’s Music store in Baltimore in 1814. (row one bottom right) The flag over Ft. McHenry (painter unknown) (row two left) 120,868,500 commemorative postage stamps were issued August 9, 1948. One of these in mint condition is worth around 60 cents today. 15 cents for a used one. (row two right) an engraving of a younger Francis Scott Key. They probably called him Frankie. (row three) The original Fort McHenry flag (15 stars and 15 stripes) measured 30 feet by 42 feet. It’s being preserved and restored in Washington, DC. (row four) Glorious isn’t it?

We’ve all been lucky to watch an amazing Olympic competition these past few weeks, with athletes from all over the world doing amazing things on the ice and snow. Each one, of course, has their own story – some competing for the first time, some competing in their third of fourth Olympics (can you imagine) and others wrapping up their Olympic careers. Consistently, every athlete talked about sacrifice, hardship and overcoming the odds, with a small few prevailing to stand on the podium, medal on chest, tears on their cheeks and hand over heart, proudly representing their county while listening to their respective national anthem. I don’t know about you, but I feel really proud when the anthem plays, and get choked up seeing the athletes realize their accomplishments.

We all know our “official” USA anthem is the Star Spangled-Banner, but what you probably didn’t know is it took 40 attempts to get it through Congress (talk about perseverance) – tomorrow, March 3th is the anniversary of the adoption of the anthem. For my trivia buds, here’s some interesting history and cool trivia about the great anthem we’ve all come to know as the strength and sound of the United States of America. Enjoy, and thanks Wikipedia, historian Mark Leepson and History.com for the info.

- A song is written. By the dawn’s early light on September 14, 1814, Francis Scott Key peered through a spyglass and spotted an American flag still waving over Baltimore’s Fort McHenry after a fierce night of British bombardment. In a patriotic fervor, the man called “Frank” Key by family and friends penned the words to “The Star-Spangled Banner.” When he composed his verses, he intended them to accompany a popular song of the day. “We know he had the tune in mind because the rhyme and meter exactly fit it,” says Marc Leepson, author of the Key biography “What So Proudly We Hailed.” The first broadside of the verses, printed just days after the battle, noted that the words should be sung to the melody of “To Anacreon in Heaven.” (ironically an English song composed in 1775 that served as the theme song of the upper-crust Anacreontic Society of London and a popular pub staple). Key was quite familiar with the tune, having used it to accompany an 1805 poem, which included a reference to a “star-spangled flag,” he had written to honor Barbary War naval heroes Stephen Decatur and Charles Stewart.

- Key was not imprisoned on a British warship when he penned his verses. In his capacity as a Washington, D.C., lawyer, Key had been dispatched by President James Madison on a mission to Baltimore to negotiate for the release of Dr. William Beanes, a prominent surgeon captured at the Battle of Bladensburg. Accompanied by John Stuart Skinner, a fellow lawyer working for the State Department, Key set sail on an American sloop in Baltimore Harbor, and on September 7 the pair boarded the British ship Tonnant, where they dined and secured the prisoner’s release under one condition—they could not go ashore until after the British attacked Baltimore. Accompanied by British guards on September 10, Key returned to the American sloop from which he witnessed the bombardment behind the 50-ship British fleet.

- The flag Key “hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming” did not fly “through the perilous fight.” In addition to a thunderstorm of bombs, a torrent of rain fell on Fort McHenry throughout the night of the Battle of Baltimore. The fort’s 30-by-42-foot garrison flag was so massive that it required 11 men to hoist when dry, and if waterlogged the woolen banner could have weighed upwards of 500 pounds and snapped the flagpole. So as the rain poured down, a smaller storm flag that measured 17-by-25 feet flew in its place. In the morning, experts believe, they most likely took down the rain-soaked storm flag and hoisted the bigger one … and that’s the flag Key saw in the morning.

- The song was not originally entitled “The Star-Spangled Banner.” When Key scrawled his lyrics on the back of a letter he pulled from his pocket on the morning of September 14, he did not give them any title. Within a week, Key’s verses were printed on broadsides and in Baltimore newspapers under the title “Defence of Fort M’Henry.” In November, a Baltimore music store printed the patriotic song with sheet music for the first time under the more lyrical title “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

- The national anthem has four verses. The version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” traditionally sung on patriotic occasions and at sporting events is only the song’s first verse. All four verses conclude with the same line: “O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.” In 1861, poet Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote a fifth verse to support the Union cause in the Civil War and denounce “the traitor that dares to defile the flag of her stars.

- Key opposed American entry into the War of 1812. Ironically, the man who created one of the lasting patriotic legacies of the War of 1812 adamantly opposed the conflict at its outset. Key referred to the war as “abominable” and “a lump of wickedness.” However, his opposition to the war softened after the British began to raid nearby Chesapeake Bay communities in 1813 and 1814, and he briefly served in a Georgetown wartime militia.

- Key was a consummate Washington insider. Although Key loathed politics, he was a prominent figure in Washington, D.C. – an important player in the early republic, He was a very successful and influential lawyer at the highest levels in Washington. Key ran a thriving law practice, served as a trusted advisor in Andrew Jackson’s “Kitchen Cabinet” and was appointed a United States Attorney in 1833. He prosecuted hundreds of cases, including that of Richard Lawrence for the attempted assassination of Court.

- Key was a one-hit wonder who might have been tone deaf. Key was much more adept in his legal day job than he was as an amateur poet. Most of the odes he composed were never meant to be seen beyond family and friends, and none came remotely close to realizing the popular fame of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” In addition to being a middling poet, Key also had a hard time carrying a tune. “Key’s family said he was not musical,” Leepson says, “which means he likely was tone deaf.”

- It did not become the national anthem until more than a century after it was written. Along with “Hail Columbia” and “Yankee Doodle,” “The Star-Spangled Banner” was among the prevalent patriotic airs in the aftermath of the War of 1812. During the Civil War, “The Star-Spangled Banner” was an anthem for Union troops, and the song increased in popularity in the ensuing decades, which led to President Woodrow Wilson signing an executive order in 1916 designating it as “the national anthem of the United States” for all military ceremonies.

- Song becomes national anthem. On March 3, 1931, after 40 previous attempts failed, a measure passed Congress and was signed into law that formally designated “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem of the United States.

- The flag restored and on display. Nearly two centuries later, the flag that inspired Key still survives, though fragile and worn by the years. Experts at the National Museum of American History completed an eight-year conservation treatment with funds from Polo Ralph Lauren, The Pew Charitable Trusts and the U.S. Congress. With the construction of the conservation lab completed in 1999, conservators clipped 1.7 million stitches from the flag to remove a linen backing that had been added in 1914, lifted debris from the flag using dry cosmetic sponges and brushed it with an acetone-water mixture to remove soils embedded in fibers. Finally, they added a sheer polyester backing to help support the flag. Said Brent D. Glass, the Museum’s Director – “The Star-Spangled Banner is a symbol of American history that ranks with the Statue of Liberty and the Charters of Freedom,” “The fact that it has been entrusted to the National Museum of American History is an honor.”