“That’s Not Art”

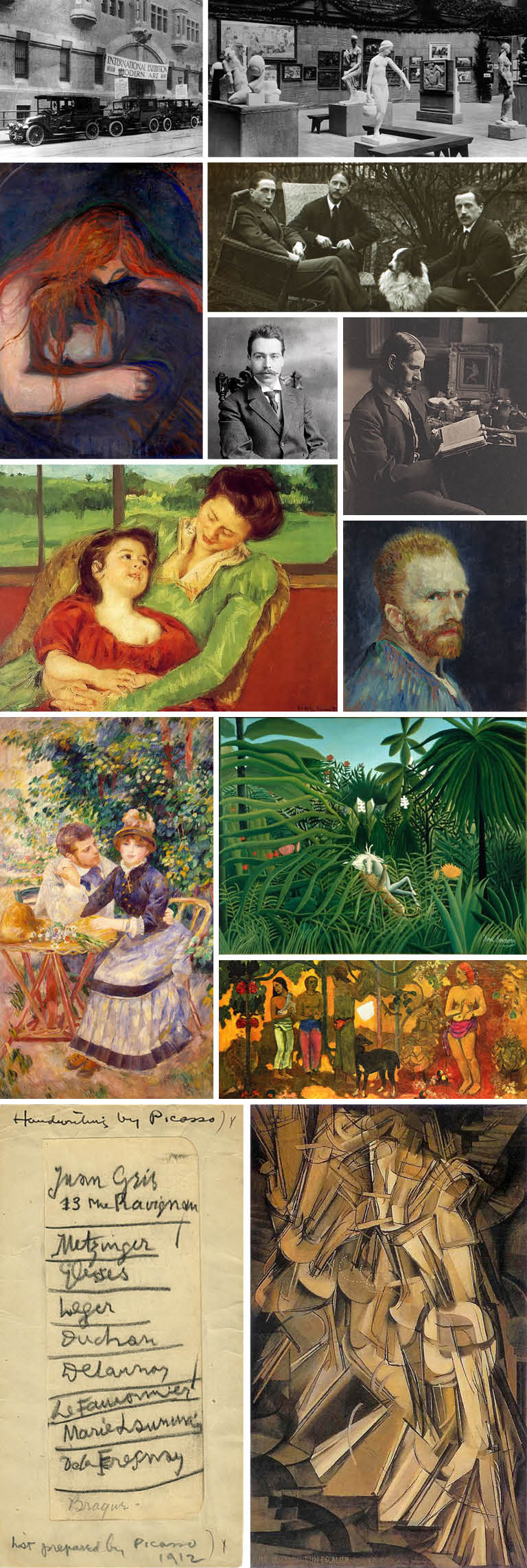

/0 Comments/in Art, Friday Afternoon, Trivia /by Steve Kowalski(top row left) Entrance of the Exhibition, 1913, New York City; (top row right) Interior view of the exhibition; (second row left) Edvard Munch-Vampire (1895); (second row right top) Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, and Villon’s dog Pipe in the garden of Villon’s studio, Puteaux, France, ca. 1913. All three brothers were included in the exhibition. (second row center) Walter_Pach,_circa_1909; (second row right bottom) Arthur B. Davies, circa 1908; (third row left) Mary Cassatt, Mère et enfant (Reine Lefebre and Margot before a Window), c.1902; (third row right) Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, c. 1887; (fourth row left) Pierre-Auguste Renoir, In The Garden 1885; (fourth row right top) Henri Rousseau, Jaguar Attacking a Horse, 1910; (fourth row right bottom) Paul Gauguin, Tahitian Pastorals, 1898; (fifth row left) A list written in 1912 by Pablo Picasso of European artists he felt should be included in the 1913 Armory Show. This document dispels the assertion that an unbridgeable divide separated the Salon Cubists from the Gallery Cubists. (fifth row right) Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912.

Throughout history, and throughout our companies, we often experience events that are real game changers. For us, it can be small things, like a certain person we hire who changes our perspectives, an investment in a new piece equipment that creates a new market opportunity, a treatment approach that solves a dilemma, or a customer who challenges us with a “real” PIA (pain in the @#$) Job!. Once the event takes place and the challenge overcome, things are just never the same. Sometimes we sit around and often laugh, reflecting back, telling “remember when” stories (think of your first cell phone). So many good, unexpected things that have happened over the years combine to make us what we are today. And the coolest part is, it’s sort of instilled a real positive, “give it a try” attitude with my team.

For me as chief bottle washer, I love it when my staff comes in and shows me how they solved a problem, or tried a new approach, and it works. We like to take time and celebrate the milestones, share the ideas, and best of all, tell you, our customers.

- This past weekend, I had the pleasure of going to the Cleveland Museum of Art – just a “day out” with my favorite “pal” – we had a blast. Inspired, I decided to write about another “event” which took place, that changed the American art world forever. Known as the NY Armory Show, a group of over 100 artists came together to share their work with the world. As often happens with “new” art, onlookers were amazed and shocked. President Teddy Roosevelt, threatening to shut down the show, decried “That’s Not Art”, joined by unhappy critics, writers and historians. Outrage was the common response. Delight was the feelings of the artists, who came together to share their new ideas, techniques and approaches. Thanks to Wikipedia, here are just some of the highlights:

- On December, 14 1911 an early meeting of what would become the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS) was organized at Madison Gallery in New York. Four artists met to discuss the contemporary art scene in the United States, and the possibilities of organizing exhibitions of progressive artworks by living American and foreign artists, favoring works ignored or rejected by current exhibitions.

- The AAPS members spent more than a year planning their first project: the International Exhibition of Modern Art, a show of giant proportions, unlike any New York had seen. The 69th Regiment Armory was settled on as the main site, designed to “lead the public taste in art, rather than follow it, rented for a fee of $5,000, plus an additional $500 for additional personnel.

- Once the space had been secured, the most complicated planning task was selecting the art for the show, particularly after the decision was made to include a large proportion of vanguard European work, most of which had never been seen by an American audience.

- Together, the key organizers went to Europe, and secured three paintings that would end up being among the Armory Show’s most famous and polarizing: Matisse’s “Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra)” and “Madras Rouge (Red Madras Headdress),”and Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.”

- The Armory Show displayed some 1,300 paintings, sculptures, and decorative works by over 300 avant-garde European and American artists. Impressionist, Fauvist, and Cubist works were represented in 18 distinct gallery areas.

- News reports and reviews were filled with accusations of quackery, insanity, immorality, and anarchy, as well as parodies, caricatures, doggerels and mock exhibitions. About the modern works, former President Theodore Roosevelt declared, “That’s not art!”. The civil authorities did not, however, close down or otherwise interfere with the show.

Here is a partial list of the artists in the show – I highlighted some of my favorites. Just imagine these differing artists, styles and statements all in one show – WOW!

Robert Ingersoll Aitken, Alexander Archipenko, George Grey Barnard, Chester Beach, Gifford Beal, Maurice Becker, George Bellows, Joseph Bernard, Guy Pène du Bois, Oscar Bluemner, Pierre Bonnard, Solon Borglum, Antoine Bourdelle, Constantin Brâncuși, Georges Braque, Bessie Marsh Brewer, Patrick Henry Bruce, Paul Burlin, Theodore Earl Butler, Charles Camoin, Arthur Carles, Mary Cassatt, Oscar Cesare, Paul Cézanne, Robert Winthrop Chanler, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, John Frederick Mowbray-Clarke, Nessa Cohen, Camille Corot, Kate Cory, Gustave Courbet, Henri-Edmond Cross, Leon Dabo, Andrew Dasburg, Honoré Daumier, Jo Davidson, Arthur B. Davies (President), Stuart Davis, Edgar Degas, Eugène Delacroix, Robert Delaunay, Maurice Denis, André Derain, Katherine Sophie Dreier, Marcel Duchamp, Georges Dufrénoy, Raoul Dufy, Jacob Epstein, Mary Foote, Roger de La Fresnaye, Othon Friesz, Paul Gauguin, William Glackens, Albert Gleizes, Vincent van Gogh, Francisco Goya, Marsden Hartley, Childe Hassam, Robert Henri, Edward Hopper, Ferdinand Hodler, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, James Dickson Innes, Augustus John, Gwen John, Wassily Kandinsky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Leon Kroll, Walt Kuhn (Founder), Gaston Lachaise, Marie Laurencin, Ernest Lawson, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Arthur Lee, Fernand Léger, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Jonas Lie, George Luks, Aristide Maillol, Édouard Manet, Henri Manguin, Edward Middleton Manigault, John Marin, Albert Marquet, Henri Matisse, Alfred Henry Maurer, Kenneth Hayes Miller, David Milne, Claude Monet, Adolphe Monticelli, Edvard Munch, Ethel Myers, Jerome Myers (Founder), Elie Nadelman, Olga Oppenheimer, Walter Pach, Jules Pascin, Francis Picabia, Pablo Picasso, Camille Pissarro, Maurice Prendergast, Odilon Redon, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Boardman Robinson, Theodore Robinson, Auguste Rodin, Georges Rouault, Henri Rousseau, Morgan Russell, Albert Pinkham Ryder, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Georges Seurat, Charles Sheeler, Walter Sickert, Paul Signac, Alfred Sisley, John Sloan, Amadeo de Souza Cardoso, Joseph Stella, Felix E. Tobeen, John Henry Twachtman, Félix Vallotton, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Jacques Villon, Maurice de Vlaminck, Bessie Potter Vonnoh, Édouard Vuillard, Abraham Walkowitz, J. Alden Weir, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Enid Yandell, Jack B. Yeats, Mahonri Young, Marguerite Zorach, William Zorach

For those of you in Cleveland looking to experience some great art this weekend, check out Brite Winter on Saturday. It’s a free art and music festival held in the Flats West Bank on Saturday, February 18th, 3PM–1AM.

Nice Moves

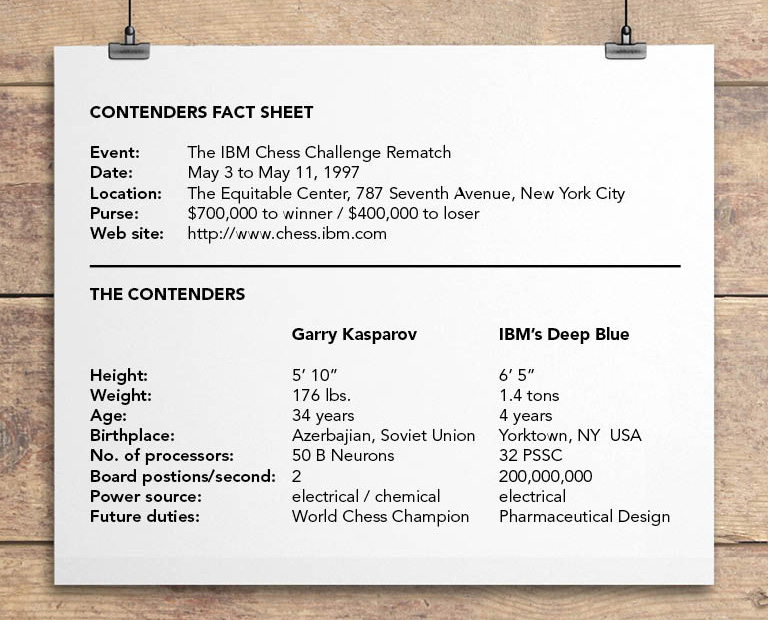

/0 Comments/in Chess, Friday Afternoon, Trivia /by Steve Kowalskitop row l to r: Gary Kasparov in 1997 training for his May rematch with an upgraded Deep Blue; Time cover May 5, 1997 (cover price $2.95); Garry Kasparov retired from professional chess March 10, 2005. This photo is from 2007.

middle row l to r: Garry at age 11; Kasparov becomes World Junior Champion at Dortmund in 1980; Kasparov-after winning the FIDE World Championship title in 1985; Interesting quote referring to Deep Blue by Yasser Seirawan.

bottom row l to r: The 6′ 5″, 1.4 ton Deep Blue; Deep Blue’s processor board; The MacBook Pro’s processor board (you’ve come a long way, baby).

Hopefully most of you had a chance to watch the Superbowl last weekend. Wow! So much to take away (I could probably use the game and coaching highlights as my blog reference and write about it for months) – effort, perseverance, hard work, leadership, strategy, witty commercials, flying Gaga, surprises and NEVER QUITTING! Dozens and dozens of top athletes going head to head competing on the world stage.

For all of the history around this game, twenty years ago on this day, another champion was on the world stage, forever changing our perception of human and machine intelligence. On Feb 10th in Philadelphia, Garry Kosparov took on Deep Blue, a chess-playing computer developed by IBM, known for being the first computer chess-playing system to win a chess game against a reigning world champion under regular time controls. Fast forward to today, chess-playing computers, and super-advanced artificial intelligence (AI), are now accessible to the average consumer. There are many chess engines to choose from, such as Stockfish, Crafty, Fruit and GNU Chess that can be downloaded for free, able to play a game that, when run on an up-to-date personal computer or mobile phone, can defeat most master players under tournament conditions. For those who have played chess, and have the inclination to learn more, here’s some trivia I know you’ll enjoy (and thanks Wikipedia for the info!)

- Using “ends-and-means” heuristics, a human chess player can intuitively determine optimal outcomes and how to achieve them regardless of the number of moves necessary, but a computer must be systematic in its analysis.

- Most players agree that looking at least five moves ahead, called five plies, when necessary is required to play well. Normal tournament rules give each player an average of three minutes per move. On average there are more than 30 legal moves per chess position, so a computer must examine a quadrillion possibilities to look ahead ten plies (five full moves); one that could examine a million positions a second would require more than 30 years.

- After discovering refutation screening (the application of alpha-beta pruning to optimizing move evaluation), in 1957, a team at Carnegie Mellon University predicted that a computer would defeat the world human champion by 1967. The team did not anticipate the difficulty of determining the right order to evaluate branches. Researchers worked to improve programs’ ability to identify killer heuristics, unusually high-scoring moves to reexamine when evaluating other branches.

- Into the 1970s, most top chess players believed that computers would not soon be able to play at a Masters level. In 1968 International Master David Levy made a famous bet that no chess computer would be able to beat him within ten years. In 1976 Senior Master and professor of psychology Eliot Hearst of Indiana University wrote that “the only way a current computer program could ever win a single game against a master player would be for the master, “perhaps in a drunken stupor while playing 50 games simultaneously, to commit some once-in-a-year blunder”.

- In the late 1970s chess programs suddenly began defeating top human players. The year of Hearst’s statement, Northwestern University’s Chess 4.5 at the Paul Masson American Chess Championship’s Class B level became the first to win a human tournament. Levy won his bet in 1978 by beating Chess 4.7, but it achieved the first computer victory against a Master-class player at the tournament level by winning one of the six games. In 1980 Belle, the first computer designed for chess playing, began often defeating Masters.

- The sudden improvement without a theoretical breakthrough surprised humans, who did not expect that Belle’s ability to examine 100,000 positions a second—about eight plies—would be sufficient. The Spracklens, creators of the successful microcomputer program Sargon, estimated that 90% of the improvement came from faster evaluation speed and only 10% from improved evaluations. New Scientist stated in 1982 that computers “play terrible chess … clumsy, inefficient, diffuse, and just plain ugly”, but humans lost to them by making “horrible blunders, astonishing lapses, incomprehensible oversights, gross miscalculations, and the like” much more often than they realized.

- By the early ‘80’s microcomputer chess programs could evaluate up to 1,500 moves a second and were as strong as mainframe chess programs of five years earlier, able to defeat almost all players. While only able to look ahead one or two plies more than at their debut in the mid-1970s, doing so improved their play more than experts expected; seemingly minor improvements “appear to have allowed the crossing of a psychological threshold, after which a rich harvest of human error becomes accessible.” In 1984 BYTE magazine wrote that “Computers—mainframes, minis, and micros—tend to play ugly, inelegant chess”, but noted Robert Byrne’s statement that “tactically they are freer from error than the average human player”.

- At the 1982 North American Computer Chess Championship, Monroe Newborn predicted that a chess program could become world champion within five years; tournament director and International Master Michael Valvo predicted ten years; the Spracklens predicted 15; Ken Thompson predicted more than 20; and others predicted that it would never happen. The most widely held opinion, however, stated that it would occur around the year 2000.

- In 1989, Levy was defeated by Deep Thought in an exhibition match. Deep Thought, however, was still considerably below World Championship Level, as the then reigning world champion Garry Kasparov demonstrated in two strong wins in 1989.

- It was not until a 1996 match with IBM’s Deep Blue that Kasparov lost his first game to a computer at tournament time controls in Deep Blue – Kasparov, 1996, Game 1. For my “chess friendly” readers, the first match went as follows: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Y9hriLylIo

- This game was, in fact, the first time a reigning world champion had lost to a computer using regular time controls. However, Kasparov regrouped to win three and draw two of the remaining five games of the match, for a convincing victory.

- In May 1997, an updated version of Deep Blue defeated Kasparov 3 1/2 – 2 1/2 in a return match. A documentary mainly about the confrontation was made in 2003, titled Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine. IBM keeps a web site of the event.

- The 1997 match took place not on a standard stage, but rather in a small television studio. The champion and computer met at the Equitable Center in New York, with cameras running, press in attendance and millions watching the outcome. The audience watched the match on television screens in a basement theater in the building, several floors below where the match was actually held. The theater seated about 500 people, and was sold out for each of the six games. The media attention given to Deep Blue resulted in more than three billion impressions around the world.

- The odds of Deep Blue winning were not certain, but the science was solid. The IBM team knew their machine could explore up to 200 million possible chess positions per second. The chess grandmaster won the first game, Deep Blue took the next one, and the two players drew the three following games. Game 6 ended the match with a crushing defeat of the champion by Deep Blue.

- The match’s outcome made headlines worldwide, and helped a broad audience better understand high-powered computing. Deep Blue had an impact on computing in many different industries. It was programmed to solve the complex, strategic game of chess, so it enabled researchers to explore and understand the limits of massively parallel processing. This research gave developers insight into ways they could design a computer to tackle complex problems in other fields, using deep knowledge to analyze a higher number of possible solutions.

- The architecture used in Deep Blue was applied to financial modeling, including marketplace trends and risk analysis; data mining—uncovering hidden relationships and patterns in large databases; and molecular dynamics, a valuable tool for helping to discover and develop new drugs.

- Ultimately, Deep Blue was retired to the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C.

The Big Game = Big Food

/0 Comments/in Food, FOOTBALL, Friday Afternoon, Fun Friday, Recipes, Super Bowl /by Steve KowalskiHave the essentials on hand:

Remote? Check.

Plenty of napkins? Check.

Add food from these starter recipes and your favorite beverage. Now sit, watch, eat, cheer!!

This weekend, we get to watch “the big game” – a tradition in our house. And with it, of course, is what I like to call “big food” – and lots of it. It’s a chance for me to go off my regiment a bit, and enjoy pretty much everything Jackie, the girls and I put out in the kitchen – old favorites, new flavors and new dishes. Aside from the traditional chips, dips, snacks, chili, vegies, desserts, and of course, my favorite (any meatball variation on the end of a toothpick or in a bowl!) I like to go looking for some recipes we may have not seen or tried before. Touchdown!! – I found a great website called delish.com with a link titled “108 Amazing Super Bowl Party Foods That Are Guaranteed to Score” (HERE) and a perfect teaser line: If your eats aren’t touchdown-worthy, your team might lose. It was tough, but here are a couple of my favorites – with over 100 ideas, I’m sure you’ll find some to try – (the Reese’s peanut butter ball just made me laugh out loud). Enjoy!

TATER TOT SKEWERS

(come on, just not fair – bacon, cheese and tater tots … should be outlawed!)

INGREDIENTS

- 1 lb. frozen tater tots, defrosted

- 12 slices bacon

- 1 cup shredded Cheddar cheese

- 2 tbsp. chives

- Ranch dressing, for serving

DIRECTIONS

- Preheat oven to 425º. Place a wire rack inside a large rimmed baking sheet.

- Place a metal rack inside a large baking pan. On a skewer, pierce one end of a strip of bacon. Pierce and place a tater top on top of the bacon, then pierce the same strip bacon again (to top the tater tot) to form a weave. Repeat with two to three more tater tots, depending on the size of your skewers. Repeat to finish the rest of the bacon and tater tots. Place on wire rack and roast for 20 to 25 minutes, until bacon is cooked through.

- Sprinkle cheese over the cooked skewers and bake until the cheese has melted, about 2-3 minutes more. Garnish with chives and serve with ranch dressing, for dipping.

JALAPEÑO CORN FRITTERS

(these are made with corn … so I figured they must be healthy, right?

INGREDIENTS

- 3 cup fresh corn

- 2/3 cup cornmeal

- 1/4 cup shredded Cheddar

- 1/4 cup cream cheese

- 2 scallions, sliced

- 2 slices cooked bacon, chopped

- 2 eggs, lightly beaten

- 1 jalapeño, finely diced

- kosher salt

- Freshly ground black pepper

- 2 tbsp. extra-virgin olive oil

- Juice of 1 lime, divided

- Sour cream, for serving

DIRECTIONS

- In a medium bowl, combine corn, cornmeal, cheddar, cream cheese, scallions, bacon, eggs, the juice of half a lime, and jalapeño. Stir to combine and season with salt and pepper to taste. Using your hands, form the mixture into small patties.

- Heat olive oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Working in batches, fry the patties until they’re golden brown, about 3 to 4 minutes per side.

- Garnish each with sour cream and a squeeze of lime, if desired.

WAFFLE FRY SLIDERS

(OMG – fries and burgers and waffles – just shoot me!! – pickles too!!)

INGREDIENTS

- 1 bag frozen waffle fries

- 1 lb. ground beef

- 2 tsp. yellow mustard

- 1/2 tsp. garlic powder

- 1/2 tsp. onion powder

- kosher salt

- Freshly ground pepper

- 1 tbsp. vegetable oil

- 2 slices of cheddar, quartered into small squares

- 1/2 cup cherry tomatoes, thinly sliced

- Bread and butter pickles, for serving

- Lettuce, for serving

DIRECTIONS

- Bake waffle fries according to package instructions. Pick out 16 large, round waffles to act as the buns.

- Meanwhile, make the sliders. In a medium bowl, mix the ground beef, yellow mustard, garlic powder and onion together with a wooden spoon. Season to taste with salt and pepper and stir gently to combine. Form the mixture into small patties. You should end up with about 8 patties.

- Heat vegetable oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Add the beef patties and cook for about 3 minutes, until the bottoms develop a nice seared crust. Flip and cook for another 1-2 minutes, then add the cheese slices to the tops of the patties. Cover the pan with a large lid and cook until cheese melts.

- Assemble the patties. Place 8 waffle fries (or however many patties you have cooked) on a serving platter. Top with cooked sliders. Then garnish with tomato slices, pickles and lettuce. Top with waffle fries and serve immediately.

If you have a family favorite, I’ll share it with the gang – just email me at skowalski@khtheat.com.